Mon, Feb 2, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 2 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(2): 59-69 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zarezade Y, Safari Y, Ashtarian H, Yousefpour N. The role of hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics by evaluating the experiences of medical students: A phenomenological study. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (2) :59-69

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2370-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2370-en.html

1- Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9311-0038

2- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health (RCEDH), Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran ,ysafari79@yahoo.com

3- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Health Faculty, KUMS, Kermanshah, Iran

4- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health (RCEDH), Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

2- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health (RCEDH), Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran ,

3- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Health Faculty, KUMS, Kermanshah, Iran

4- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health (RCEDH), Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 436 kb]

(695 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1211 Views)

Full-Text: (125 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Role modeling by physicians plays a key role in shaping the professional competencies, values, and attitudes of medical students. It is particularly significant for students in clinical education settings. This phenomenological study aimed to elucidate the role of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Materials & Methods: A qualitative approach utilizing a phenomenological method was conducted with a purposive sample of 12 final-year medical students from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences during their internship period. The data collection method was a semi-structured interview. The mean duration of each interview was 75 minutes. Data interpretation was performed using Colaizzi's seven-step approach.

Results: Overall, six main themes emerged from the data, which include (1) Modeling professional ethics directly and indirectly through the training and behavior of professors, (2) Modeling professional ethics from societal influences and non-professional interactions with professors, (3) Modeling positive or negative professional ethics based on external circumstances (4) Motivation for students to emulate professional ethics (5) Beliefs in possessing inherent abilities to model professional ethics (6) Characteristics of professors as models of professional ethics.

Conclusion: According to the results of this study, students play a significant role in modeling for professors the importance of acquiring professional ethics. This involves improving educational conditions, encouraging teachers to be mindful of their behavior in clinical environments, and creating suitable modeling opportunities. Additionally, it is recommended to increase the number of professors who can serve as role models in professional ethics.

It is essential to recognize that the primary objective of teaching students is to shape medical professional ethics, foster a professional identity, impart ethical principles, address challenging clinical experiences, eliminate negative role models among doctors in clinical settings, and modify students' attitudes [10]. Therefore, it seems necessary to have a suitable curriculum for teaching these competencies. The study by de Lemos Tavares et al. [11] titled "Understanding the Methods Used in the Teaching of Bioethics in Medical Education Worldwide," analyzed 2,993 articles, of which 72 met the pre-selected criteria and were included in the review. The characteristics of bioethics education that stood out in the analysis included the following: significant heterogeneity in teaching across different universities, the use of various methodologies in the teaching and learning process, and disconnection between education and the student's medical practice. This highlights the need to integrate the curriculum with clinical practice and address the challenges in the teaching and learning process. Most studies in this review suggest that there are currently no established minimum parameters for the ideal method of teaching bioethics. This lack of consensus may contribute to students feeling unprepared to confront ethical issues in clinical practice despite having acquired the necessary theoretical knowledge [12]. Sullivan et al., in a study titled "A Novel Peer-Directed Curriculum to Enhance Medical Ethics Training for Medical Students: A Single-Institution Experience," stated that rassroots medical ethics education emphasizes experiential learning and peer-to-peer informal discourse of everyday ethical considerations in the health care setting. Student engagement in curricular development, reflective practice in clinical settings, and peer-assisted learning are strategies to enhance clinical ethics education [13]. Garza et al. study under the title "Teaching Medical Ethics in Graduate and Undergraduate Medical Education". None of the trials incorporated psychiatry residents. Ethics educators should undertake additional rigorously controlled trials to secure a strong evidence base for the design of medical ethics curricula. Psychiatry ethics educators can also benefit from the findings of trials in other disciplines and undergraduate medical education [14]. Passi et al. [15] demonstrate that students are influenced by their teachers' behavior, which serves as role modeling. This modeling sometimes occurs positively and sometimes in a negative manner. Therefore, what is transferred to students in the form of direct education does not necessarily mean the formation of professional ethics in them; rather, the positive and negative modeling of professors occurs indirectly and without prior intention. This topic addresses the process of students learning through the role modeling of their professors. For this reason, every day, the influence of clinical environments is greater than the influence of formal education curricula [16]. By reviewing previous studies, it can be acknowledged that despite being educated about medical ethics and professionalism, students often exhibit unethical behaviors. It seems that a change in the teaching of professional ethics is necessary [17]. The results of these studies primarily indicate the negative impact of the hidden curriculum. Some aspects of communication attributed to the hidden curriculum are related to the non-formal curriculum. This process shows that professional ethics training is not ideal [18]. Therefore, preparing and revising the curriculum of professional ethics and incorporating it into the educational content is considered necessary to improve the level of professors' abilities in developing students' professional ethics [19]. Moreover, disproportionate attention to the scientific dimensions of the curriculum has led to neglect of other dimensions and their role in shaping professional ethics [20]. The literature frequently depicts the hidden curriculum as negative or in conflict with the formal curriculum. However, the hidden curriculum can have a profoundly positive impact on students' experiences and their development of professionalism. In addition, studies have shown the negative outcomes of the hidden curriculum, such as the problem of transferring professional values and ethics. Future researchers should focus on the positive outcomes as a strategy to compensate for the loss of professional ethics [21].

Considering the importance of the subject and the existing information gap in this field, this research was designed and implemented to explore the role of the hidden curriculum in shaping professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences using a phenomenological method.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The present study employed a qualitative approach with a phenomenological method at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in 2013. Husserl is a key figure in phenomenology, and his goal was to gain a deeper understanding of fundamental aspects of human experience, such as time, purpose, color, and number. Phenomenology attempts to understand how participants make sense of their experiences. A phenomenologist considers the meanings of experience and describes the life world [22].

Participants and sampling

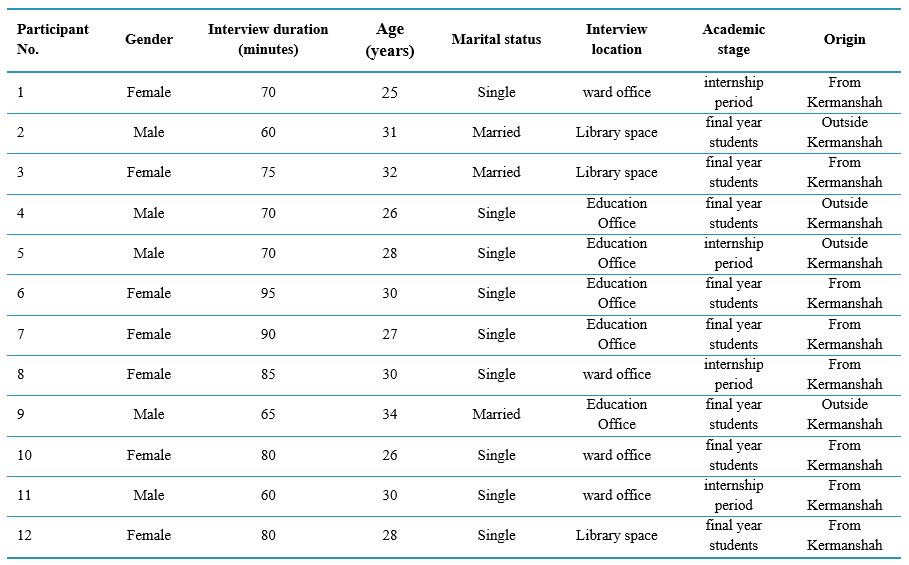

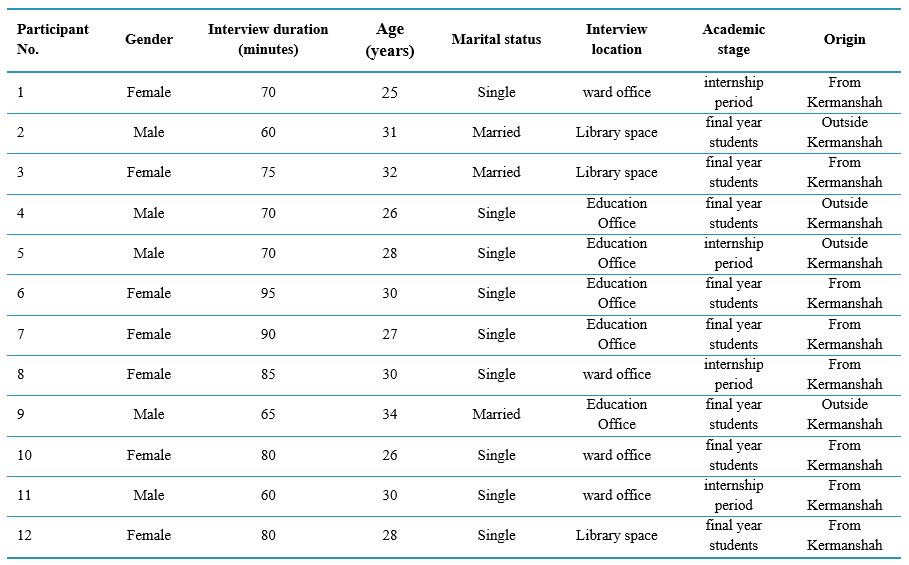

The study's statistical population consists of all internship-period students and final-year medical students. Sample selection was purposeful and based on the principle of theoretical saturation. The number of samples reached 12 participants with theoretical saturation. Information about the participants is presented in Table 1.

The criterion for achieving data saturation in this study was the repetition of previous data, allowing researchers to encounter data that were repeated regularly. In this study, the researchers encountered repetitive codes during data coding until no new themes were identified from the interviews. As a result, the flow of data collection was stopped. Sampling was performed by purposive method. Purposive sampling is a method widely used in qualitative research to identify and select high-quality items for the most effective use of limited resources. This includes identifying and selecting individuals or groups of individuals who possess the most experience and knowledge, particularly about the phenomenon [23].

Data collection methods

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. Before the interview, each participant was contacted via mobile phone. In a separate face-to-face meeting, the participants were also satisfied. Verbal consent was obtained from participants to partake in the interviews, and the necessary explanations were provided for this purpose. The interviews began with general key questions and progressed to more detailed inquiries. Sample interview key questions include: "Who did your role model in your experiences in medical education?" "What characteristics did these role models have?" "What was the nature of these role model experiences?" "What impact did the role models have on your professional life?" "Who and how have you experienced ethical modeling?" All interviews were simultaneously recorded, and attempts were made to confirm the interviewer's perception of the participants. The data obtained from each interview were coded and interpreted immediately after data collection. Efforts were also made to gain participants' trust and understanding of the research environment. Three individuals who were already familiar with the qualitative research and coding process coded three records to assess the accuracy and objectivity of the data. The coefficient of similarity between the coders was estimated to be at an acceptable level. After coding, the texts were returned to some participants to confirm the accuracy of the extracted codes and interpretations, allowing the researcher to reach a similar understanding. All participant statements were recorded and noted during the interview and confirmed by the participants at the same time. In cases where there was ambiguity about the statement, it was reconciled with the participants by telephone to avoid errors in data interpretation and coding. The data obtained from each interview were analyzed using a phenomenological approach.

Data analysis

In this study, Colaizzi's seven-step approach was employed to interpret the data. The informants' first explanations of the experiences are read to gain a general sense. Substantial expressions are then extracted. Meanings are formulated from important propositions. The meanings formulated in the themes are organized. Themes are integrated into a comprehensive description. The basic structure of the phenomenon is formulated. Finally, to validate the information provided by the participants, the analysis results are evaluated to determine if they align with their initial experiences [24].

Various methods were employed throughout the study to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data. Efforts were made to build trust with participants and enhance their perception of the research environment through long-term communication and consistent contact with the research sites. Three individuals were responsible for coding the data to ensure its accuracy and objectivity. After coding, the transcripts were returned to some participants to confirm the accuracy of the extracted codes and interpretations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

Results

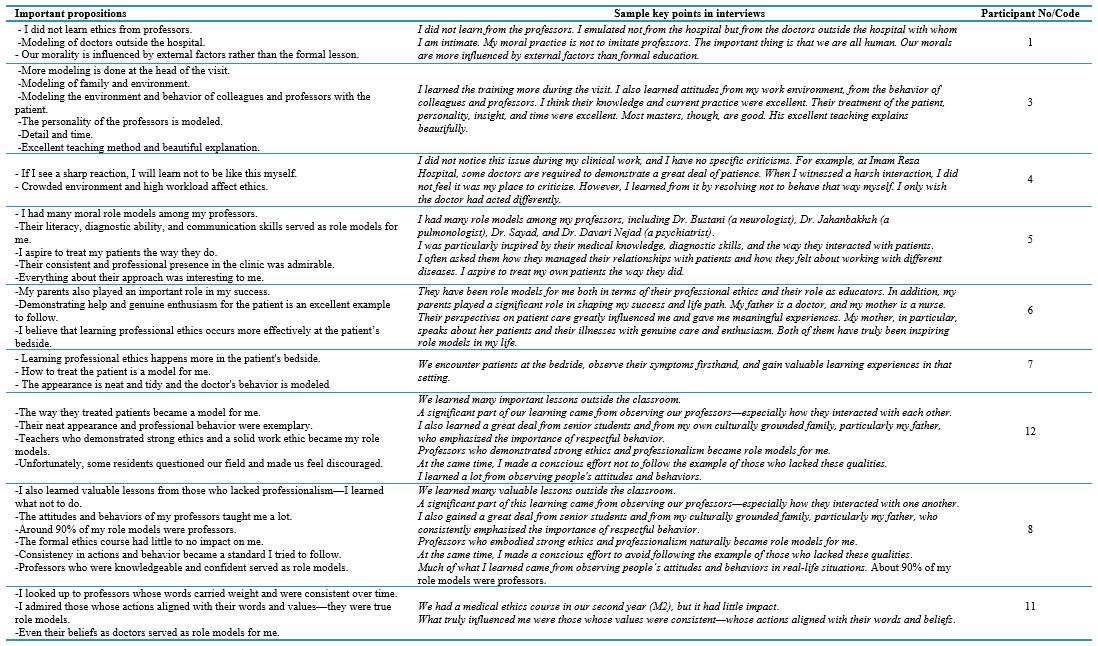

In the present phenomenological study, the researcher conducted the interviews personally. This was very helpful in achieving a holistic sense of all the participants' experiences. Audio recordings were listened to multiple times, and the typed transcripts were read carefully to gain a deeper understanding of the participants' thoughts and feelings. The researcher extracted significant phrases from the typed text, studied them multiple times, and analyzed the content to capture the whole meaning of the experience. This process was conducted to identify key phrases within the interview transcripts. These statements were made separately for each participant. A total of 188 codes were extracted.

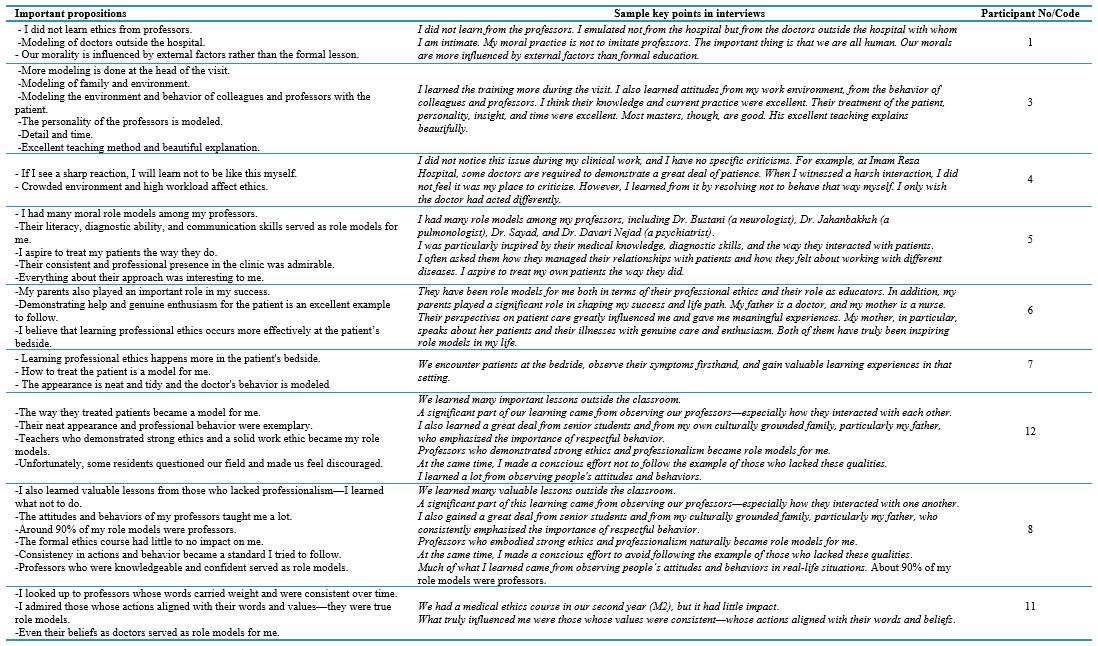

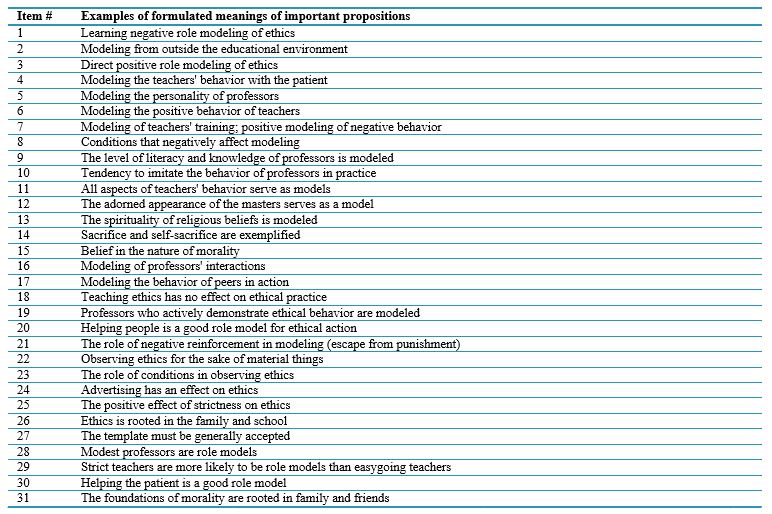

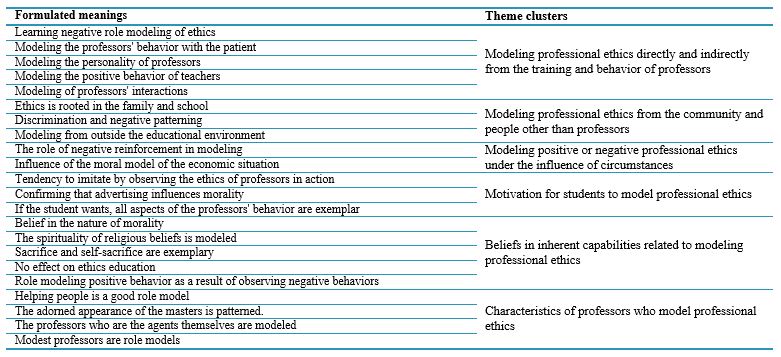

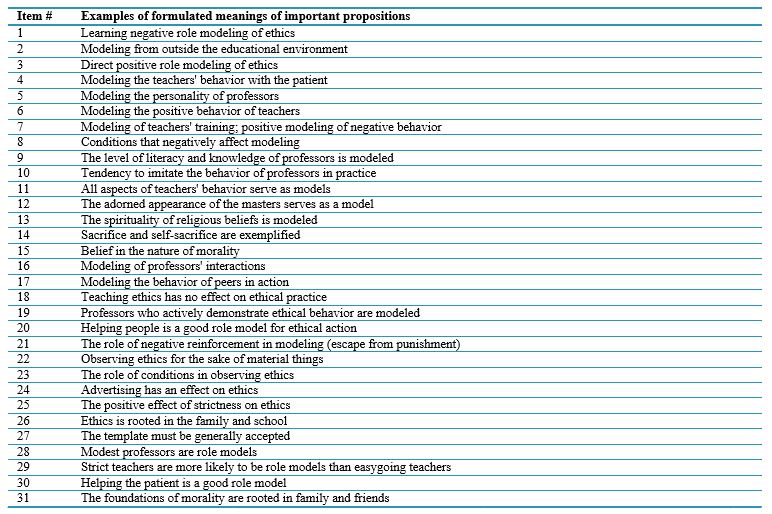

Since all the codes are extensive, Table 2 presents a selection of statements from the interviews along with examples of coding from the interview transcripts. These codes were randomly chosen from four interview. At formulation of meanings, the researcher attempted to formulate more general retellings or meanings for each important phrase in the text. Meanings were formulated from important sentences. This is necessary because it helps to prevent misinterpretation of the participant's views. These formulated meanings were then coded and categorized. At this stage, 31 codes were derived from the total of 188 codes obtained in the second stage. Table 3 shows 31 codes that show how important phrases became formulated meanings.

Table 2. Examples of important propositions

Table 3. Examples of formulated meanings of important propositions

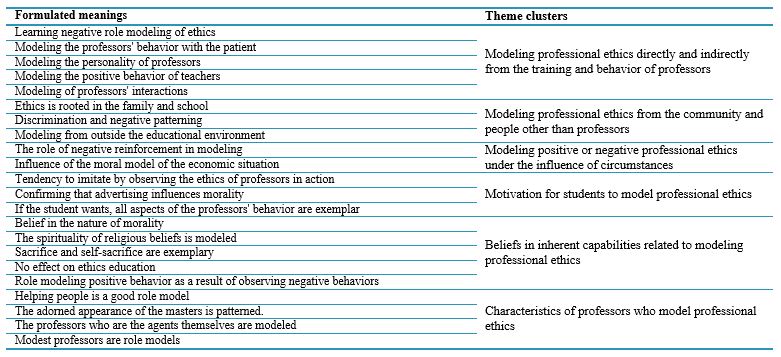

After obtaining the formulated meanings of the important propositions, the researcher arranged them into categories of themes. The subthemes were then consolidated into emerging themes, indicating that each "formulated meaning" originates from a single cluster of themes. At this stage, the 31 subthemes derived from the students' interview experiences were combined and condensed, resulting in a total of six main themes. These themes are shown in Table 4. Findings from the interviews led to the identification of main themes through an inductive process and the formulation of meaningful insights. Sample themes and participants' statements regarding each theme are presented below.

Table 4. Create clusters of themes derived from formulated meanings

Modeling professional ethics directly and indirectly from professors

Participant 1 (Born in 1995, non-native,. Final year of medicine) said,

"I didn't learn from the professors; I also learned from my work environment, from the behavior of my colleagues and professors, and their regular presence at the clinic." "Everything about them was interesting to me." "They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role." "The way they regularly attend the clinic." "Everything about them has been interesting to me." "They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role."

Modeling professional ethics from the community

Participant 3 (Final year of medicine student p , native, married) said,

"I took as a model the behavior of many people other than professors." "More than 90% of the interactions with others were from professors". "I learned ethics from my family and friends." "I don't have anything special to say, but I can only say that external factors more influence our morality than formal lessons."

Modeling professional ethics under the influence of circumstances

Participant 4 (Intern student, native, single) said,

"Regarding professional ethics, I must say that there are several issues that we grew up with and were influenced by since childhood. I didn't learn from professors." "We see the patient at the bedside, we see the symptoms of their illness, and we learn a lot of things there. Passing classes has no effect."

Motivation for students to model professional ethics

Participant 5 (Intern. Non-native and single) said,

"I determine most of it myself." "I modeled it not on the hospital, but on doctors outside the hospital who I am close to." "I do what I know is right." "Medicine is both profitable and accepted in society." "This motivates me to uphold the etiquette."

Beliefs in having inherent capabilities in modeling professional ethics

Participant 12 (Intern, non-native, single) said,

"I like helping patients because of my conscience and the good feeling it gives me." "I believe that if a person's nature is pure, they will observe morality." "I consider God more. I don't care what other people think or approve of me in this regard." "If your essence is pure, everything will be fine."

Characteristics of professors who model professional ethics

Participant 7 (Final year of medicine student , intern, native, single) said,

"I was interested in the type of relationship the professors had with the patients." "They're asking about the patient's well-being. Their satisfaction with the type of illness". "I would like to treat my patients like they do. Their regular presence at the clinic." "I was interested in everything about them. They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role".

Discussion

Medical science professors are a key element in medical ethics education, as they can shape the moral and professional character of students. This study aimed to explain the role of the hidden curriculum in shaping professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. From the interviews, a total of 188 open codes were identified. By merging codes with similar themes during the axial coding stage, a total of 36 axial codes, or subthemes, were generated. In the third stage, the researcher obtained categories for the six main themes.

The first main theme obtained from the data analysis was "modeling professional ethics from the teaching and behavior of professors directly and indirectly." This theme included six categories of subthemes, including "Negative moral patterns, professors' behavior with patients, professors' personality, professors' positive behavior, professors' training, and interactions." In line with these results, studies have shown that personal factors, including individual characteristics, as well as interpersonal and environmental factors, play a role in the professional ethics of doctors. Furthermore, students tend to emulate what their professors do rather than what they say [25]. This suggests that the impact of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum. Some studies show that, just as professors’ deal with students, students will also deal with their patients, colleagues, and future students. Therefore, students model the behavior of their teachers. Of course, this modeling occurs in both positive and negative ways. In any case, medical students receive both positive and negative messages from the clinical environment during their internship period [14, 15]. The second main theme obtained was "modeling professional ethics from society and people other than professors." This main theme had subthemes including: "Ethical observance is rooted in family and school, discrimination and favoritism play a negative role model, the foundations of morality in family and friends, role modeling from peers, role modeling outside the educational environment." In line with the results of this study, some studies have found that friends and family members influence students when it comes to learning medical ethics. Most of them believe that the influence of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum [16]. The third theme obtained was "modeling positive or negative professional ethics under the influence of circumstances." This main theme included subthemes, categorized as follows: "conditions that hurt role modeling," "the presence of special conditions affecting role modeling," "the role of negative reinforcement in role modeling," and "the influence of moral role models on economic status." In some studies, students reported that learning medical ethics is influenced by individual factors, such as self-efficacy and moral competence, which affect their professional growth and motivation to cooperate with members of the therapy team in improving their competence and clinical performance [26]. According to the findings, having proper communication as well as having an encouragement and support system and having specific rules facilitating professionalism and the inadequacies of the organizational and management system of the Ministry of Health and the educational system and not paying attention to the hidden curriculum in the transfer of professionalism characteristics, is one of the obstacles of professionalism. The fourth main theme included "Motivation for modeling professional ethics by students." This theme included four subthemes categories: "tendency to identify with professors," "the role of advertising in professional ethics," "general acceptability of the role model," and "students' tendency to imitate the teacher's behavior." In line with the results of this study, the research demonstrated that the willingness to cooperate with members of the treatment team is effective in enhancing the competence and clinical performance of students. Burgess et al. showed that students imitate the characteristics and behaviors they aspire to have as doctors in the future [9]. Some professors possess characteristics that motivate students to aspire to be role models. On the other hand, some professors lack these characteristics, and students have no motivation to imitate their behavior. In any case, the student must follow the model and emulate the model's behavior. Therefore, having the motivation and intention for this work has a great impact on the role model of students [27]. The fifth main theme included "Beliefs in having inherent capabilities in modeling professional ethics." This main theme consists of five subthemes c: "Belief in the innateness of morality," "The spirituality of religious beliefs are modeled, "Sacrifice and self-sacrifice are modeled, "The lack of influence of education on moral modeling," and "Positive modeling of negative behavior." In line with this finding, looking at the research conducted on the components of professors' professional ethics, it shows that some components, such as the acceptance of different cultural and religious contexts, affect modeling the role of professional ethics [8]. Therefore, the inherent characteristics of students play a role in modeling. Due to this process, an optimal model may be obtained from inappropriate behavior, and conversely, a negative model may be derived from positive behavior. The proverb "Learning politeness from rude people" can be an example of this issue. The sixth main theme identified was "characteristics of professors who model professional ethics." This main theme consists of seven categories: "the level of literacy and knowledge of professors becomes a role model," "helping people is a good role model," "the well-groomed appearance of professors becomes a role model," teachers who are agents themselves become role models," "They are humble role models," "Professors are role models, they are strict," "Helping the patient is a good role model." This topic refers to the process of role modeling by students from professors. For this reason, the influence of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum every day. Some of the characteristics that are modeled include specialized competence, recognition of comprehensive dimensions, standard evaluation, adherence to organizational rules, and appropriate interaction with colleagues. Moreover, the most important characteristic of an exemplary professor from the student's point of view is "mastery of the professor and general knowledge is mentioned about the subject being taught [28, 29]. In contrast to the findings of this study, the determination and strictness of professors were identified as the least important characteristics. Additionally, the presentation of engaging course material, the professor's fluency, a close relationship between the professor and students, and appropriate eye contact were also noted as qualities of effective professors. [26]. Lempp and Seale and Safari et al. introduced professors as role models who have been encouraging and motivating roles for them. The commitment and adherence of these professors to teaching and communicating with students, patients, and colleagues are exemplary [30, 31]. As is known, while some of the components expressed in studies on the characteristics of model professors are consistent with the results of the present study, others differ. This is due to the difference in the goals of these studies. This means that some studies focus on individual factors, some on social factors, and some on organizational factors.

The data collection method used in this study was interviews, which come with their limitations. This study was no exception; for example, individual differences among participants may have influenced the rate at which they responded to the interview questions. Therefore, it should be expected that the findings of this study cover all the components of professional ethics. However, many studies confirm the results of this study. In conclusion, it is important to emphasize that, given the significance of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics, it is essential to create conducive conditions for modeling and to take steps toward establishing a healthy environment. Additionally, fostering an appealing atmosphere that encourages the modeling of positive behaviors is necessary. It is recommended to incorporate aspects of professional ethics into the selection of medical students. According to the study's researchers, medical professors need to view themselves as obligated to instill the professional ethics of being a doctor in their students while teaching the fundamental concepts of medical ethics. In addition to imparting medical skills, they should also prioritize teaching medical ethics to both current students and future doctors.

Conclusion

The findings revealed six main themes related to the role of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics. These themes include "direct and indirect modeling," "modeling from society," "modeling under the influence of circumstances," "the necessity of motivation for modeling," "belief in inherent capabilities for modeling," and "characteristics of teachers as models of professional ethics." According to the results of this study, clinical professors play a significant role as role models for students in developing professional ethics. It is crucial to improve educational environments, encourage teachers to be mindful of their behavior in clinical settings, create appropriate modeling opportunities, and increase the number of professors who can serve as role models in professional ethics.

Ethical considerations

To uphold ethical considerations, participation in the study was voluntary, and participants had the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. As mentioned, informed consent was obtained from participants, and the instruments contained no personally identifiable information and were coded to ensure that the participants answered voluntarily and freely. The study was registered and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virtual University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.VUMS.REC.1399.007).

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

No artificial intelligence was utilized in writing this article.

Acknowledgment

The participants in this study were final-year medicine students at the internship level, and we hereby thank all of them. This article is extracted from the master's thesis in the field of medical education at the Virtual University of Medical Sciences in Iran.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the work.

Funding

The article was written without any financial support.

Data availability statement

The data is available and can be provided to the editor or other responsible individuals at any time. For access, please contact the corresponding author at: ysafari79@yahoo.com.

Background & Objective: Role modeling by physicians plays a key role in shaping the professional competencies, values, and attitudes of medical students. It is particularly significant for students in clinical education settings. This phenomenological study aimed to elucidate the role of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Materials & Methods: A qualitative approach utilizing a phenomenological method was conducted with a purposive sample of 12 final-year medical students from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences during their internship period. The data collection method was a semi-structured interview. The mean duration of each interview was 75 minutes. Data interpretation was performed using Colaizzi's seven-step approach.

Results: Overall, six main themes emerged from the data, which include (1) Modeling professional ethics directly and indirectly through the training and behavior of professors, (2) Modeling professional ethics from societal influences and non-professional interactions with professors, (3) Modeling positive or negative professional ethics based on external circumstances (4) Motivation for students to emulate professional ethics (5) Beliefs in possessing inherent abilities to model professional ethics (6) Characteristics of professors as models of professional ethics.

Conclusion: According to the results of this study, students play a significant role in modeling for professors the importance of acquiring professional ethics. This involves improving educational conditions, encouraging teachers to be mindful of their behavior in clinical environments, and creating suitable modeling opportunities. Additionally, it is recommended to increase the number of professors who can serve as role models in professional ethics.

Introduction

The role of the hidden curriculum in developing professional ethics as a basis for learning communication skills with patients is a key issue in the medical profession, and this issue, along with other professions, is implicitly considered a component of the hidden curriculum in medicine. Evidence suggests a strong relationship between the hidden curriculum and professional development [1]. This is because the formal education provided by university courses in many faculties worldwide has failed to achieve the goals related to the development of professional ethics in learners [2]. Paying attention to the hidden curriculum is crucial in providing a platform for the development of ethics, as learners often acquire ethics through the environment and atmosphere created by the curriculum. Therefore, universities teach students more than what do they claim [3]. Although some elements of the curriculum must be determined in advance, a wide range of teaching methods should be considered at the time of implementation to maximize learning opportunities. Therefore, the hidden curriculum is sometimes in line and occasionally in conflict with the official curriculum [4]. As a research methodology, phenomenology is uniquely positioned to help health professions education (HPE) scholars learn from the experiences of others. Phenomenology is a form of qualitative research that focuses on the study of an individual's lived experiences within the world [5]. Philip Jackson defined the term “hidden curriculum” in 1968 to describe the attitudes and beliefs that children must learn as part of the socialization process to succeed in school. Frederic Hafferty first defined the term medical education and was the first to apply this concept to the medical field in 1994 [6]. A study entitled "Role Models and Teachers" demonstrates that doctors in training are not merely recipients of the hidden curriculum; instead, they actively engage with ethics in the workplace, influenced by their perceptions of values [7]. Meanwhile, role modeling by doctors helps in developing the professional competencies, values, and attitudes of medical students. The three main characteristics of a positive role model include clinical skills, teaching abilities, and personal qualities [8]. Role modeling is important for students in clinical education settings. Clinical professors' awareness of their professional characteristics, attitudes, and behaviors can help create better teaching-learning experiences [9].It is essential to recognize that the primary objective of teaching students is to shape medical professional ethics, foster a professional identity, impart ethical principles, address challenging clinical experiences, eliminate negative role models among doctors in clinical settings, and modify students' attitudes [10]. Therefore, it seems necessary to have a suitable curriculum for teaching these competencies. The study by de Lemos Tavares et al. [11] titled "Understanding the Methods Used in the Teaching of Bioethics in Medical Education Worldwide," analyzed 2,993 articles, of which 72 met the pre-selected criteria and were included in the review. The characteristics of bioethics education that stood out in the analysis included the following: significant heterogeneity in teaching across different universities, the use of various methodologies in the teaching and learning process, and disconnection between education and the student's medical practice. This highlights the need to integrate the curriculum with clinical practice and address the challenges in the teaching and learning process. Most studies in this review suggest that there are currently no established minimum parameters for the ideal method of teaching bioethics. This lack of consensus may contribute to students feeling unprepared to confront ethical issues in clinical practice despite having acquired the necessary theoretical knowledge [12]. Sullivan et al., in a study titled "A Novel Peer-Directed Curriculum to Enhance Medical Ethics Training for Medical Students: A Single-Institution Experience," stated that rassroots medical ethics education emphasizes experiential learning and peer-to-peer informal discourse of everyday ethical considerations in the health care setting. Student engagement in curricular development, reflective practice in clinical settings, and peer-assisted learning are strategies to enhance clinical ethics education [13]. Garza et al. study under the title "Teaching Medical Ethics in Graduate and Undergraduate Medical Education". None of the trials incorporated psychiatry residents. Ethics educators should undertake additional rigorously controlled trials to secure a strong evidence base for the design of medical ethics curricula. Psychiatry ethics educators can also benefit from the findings of trials in other disciplines and undergraduate medical education [14]. Passi et al. [15] demonstrate that students are influenced by their teachers' behavior, which serves as role modeling. This modeling sometimes occurs positively and sometimes in a negative manner. Therefore, what is transferred to students in the form of direct education does not necessarily mean the formation of professional ethics in them; rather, the positive and negative modeling of professors occurs indirectly and without prior intention. This topic addresses the process of students learning through the role modeling of their professors. For this reason, every day, the influence of clinical environments is greater than the influence of formal education curricula [16]. By reviewing previous studies, it can be acknowledged that despite being educated about medical ethics and professionalism, students often exhibit unethical behaviors. It seems that a change in the teaching of professional ethics is necessary [17]. The results of these studies primarily indicate the negative impact of the hidden curriculum. Some aspects of communication attributed to the hidden curriculum are related to the non-formal curriculum. This process shows that professional ethics training is not ideal [18]. Therefore, preparing and revising the curriculum of professional ethics and incorporating it into the educational content is considered necessary to improve the level of professors' abilities in developing students' professional ethics [19]. Moreover, disproportionate attention to the scientific dimensions of the curriculum has led to neglect of other dimensions and their role in shaping professional ethics [20]. The literature frequently depicts the hidden curriculum as negative or in conflict with the formal curriculum. However, the hidden curriculum can have a profoundly positive impact on students' experiences and their development of professionalism. In addition, studies have shown the negative outcomes of the hidden curriculum, such as the problem of transferring professional values and ethics. Future researchers should focus on the positive outcomes as a strategy to compensate for the loss of professional ethics [21].

Considering the importance of the subject and the existing information gap in this field, this research was designed and implemented to explore the role of the hidden curriculum in shaping professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences using a phenomenological method.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The present study employed a qualitative approach with a phenomenological method at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in 2013. Husserl is a key figure in phenomenology, and his goal was to gain a deeper understanding of fundamental aspects of human experience, such as time, purpose, color, and number. Phenomenology attempts to understand how participants make sense of their experiences. A phenomenologist considers the meanings of experience and describes the life world [22].

Participants and sampling

The study's statistical population consists of all internship-period students and final-year medical students. Sample selection was purposeful and based on the principle of theoretical saturation. The number of samples reached 12 participants with theoretical saturation. Information about the participants is presented in Table 1.

The criterion for achieving data saturation in this study was the repetition of previous data, allowing researchers to encounter data that were repeated regularly. In this study, the researchers encountered repetitive codes during data coding until no new themes were identified from the interviews. As a result, the flow of data collection was stopped. Sampling was performed by purposive method. Purposive sampling is a method widely used in qualitative research to identify and select high-quality items for the most effective use of limited resources. This includes identifying and selecting individuals or groups of individuals who possess the most experience and knowledge, particularly about the phenomenon [23].

Data collection methods

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews. Before the interview, each participant was contacted via mobile phone. In a separate face-to-face meeting, the participants were also satisfied. Verbal consent was obtained from participants to partake in the interviews, and the necessary explanations were provided for this purpose. The interviews began with general key questions and progressed to more detailed inquiries. Sample interview key questions include: "Who did your role model in your experiences in medical education?" "What characteristics did these role models have?" "What was the nature of these role model experiences?" "What impact did the role models have on your professional life?" "Who and how have you experienced ethical modeling?" All interviews were simultaneously recorded, and attempts were made to confirm the interviewer's perception of the participants. The data obtained from each interview were coded and interpreted immediately after data collection. Efforts were also made to gain participants' trust and understanding of the research environment. Three individuals who were already familiar with the qualitative research and coding process coded three records to assess the accuracy and objectivity of the data. The coefficient of similarity between the coders was estimated to be at an acceptable level. After coding, the texts were returned to some participants to confirm the accuracy of the extracted codes and interpretations, allowing the researcher to reach a similar understanding. All participant statements were recorded and noted during the interview and confirmed by the participants at the same time. In cases where there was ambiguity about the statement, it was reconciled with the participants by telephone to avoid errors in data interpretation and coding. The data obtained from each interview were analyzed using a phenomenological approach.

Data analysis

In this study, Colaizzi's seven-step approach was employed to interpret the data. The informants' first explanations of the experiences are read to gain a general sense. Substantial expressions are then extracted. Meanings are formulated from important propositions. The meanings formulated in the themes are organized. Themes are integrated into a comprehensive description. The basic structure of the phenomenon is formulated. Finally, to validate the information provided by the participants, the analysis results are evaluated to determine if they align with their initial experiences [24].

Various methods were employed throughout the study to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data. Efforts were made to build trust with participants and enhance their perception of the research environment through long-term communication and consistent contact with the research sites. Three individuals were responsible for coding the data to ensure its accuracy and objectivity. After coding, the transcripts were returned to some participants to confirm the accuracy of the extracted codes and interpretations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

Results

In the present phenomenological study, the researcher conducted the interviews personally. This was very helpful in achieving a holistic sense of all the participants' experiences. Audio recordings were listened to multiple times, and the typed transcripts were read carefully to gain a deeper understanding of the participants' thoughts and feelings. The researcher extracted significant phrases from the typed text, studied them multiple times, and analyzed the content to capture the whole meaning of the experience. This process was conducted to identify key phrases within the interview transcripts. These statements were made separately for each participant. A total of 188 codes were extracted.

Since all the codes are extensive, Table 2 presents a selection of statements from the interviews along with examples of coding from the interview transcripts. These codes were randomly chosen from four interview. At formulation of meanings, the researcher attempted to formulate more general retellings or meanings for each important phrase in the text. Meanings were formulated from important sentences. This is necessary because it helps to prevent misinterpretation of the participant's views. These formulated meanings were then coded and categorized. At this stage, 31 codes were derived from the total of 188 codes obtained in the second stage. Table 3 shows 31 codes that show how important phrases became formulated meanings.

Table 2. Examples of important propositions

Table 3. Examples of formulated meanings of important propositions

After obtaining the formulated meanings of the important propositions, the researcher arranged them into categories of themes. The subthemes were then consolidated into emerging themes, indicating that each "formulated meaning" originates from a single cluster of themes. At this stage, the 31 subthemes derived from the students' interview experiences were combined and condensed, resulting in a total of six main themes. These themes are shown in Table 4. Findings from the interviews led to the identification of main themes through an inductive process and the formulation of meaningful insights. Sample themes and participants' statements regarding each theme are presented below.

Table 4. Create clusters of themes derived from formulated meanings

Modeling professional ethics directly and indirectly from professors

Participant 1 (Born in 1995, non-native,. Final year of medicine) said,

"I didn't learn from the professors; I also learned from my work environment, from the behavior of my colleagues and professors, and their regular presence at the clinic." "Everything about them was interesting to me." "They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role." "The way they regularly attend the clinic." "Everything about them has been interesting to me." "They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role."

Modeling professional ethics from the community

Participant 3 (Final year of medicine student p , native, married) said,

"I took as a model the behavior of many people other than professors." "More than 90% of the interactions with others were from professors". "I learned ethics from my family and friends." "I don't have anything special to say, but I can only say that external factors more influence our morality than formal lessons."

Modeling professional ethics under the influence of circumstances

Participant 4 (Intern student, native, single) said,

"Regarding professional ethics, I must say that there are several issues that we grew up with and were influenced by since childhood. I didn't learn from professors." "We see the patient at the bedside, we see the symptoms of their illness, and we learn a lot of things there. Passing classes has no effect."

Motivation for students to model professional ethics

Participant 5 (Intern. Non-native and single) said,

"I determine most of it myself." "I modeled it not on the hospital, but on doctors outside the hospital who I am close to." "I do what I know is right." "Medicine is both profitable and accepted in society." "This motivates me to uphold the etiquette."

Beliefs in having inherent capabilities in modeling professional ethics

Participant 12 (Intern, non-native, single) said,

"I like helping patients because of my conscience and the good feeling it gives me." "I believe that if a person's nature is pure, they will observe morality." "I consider God more. I don't care what other people think or approve of me in this regard." "If your essence is pure, everything will be fine."

Characteristics of professors who model professional ethics

Participant 7 (Final year of medicine student , intern, native, single) said,

"I was interested in the type of relationship the professors had with the patients." "They're asking about the patient's well-being. Their satisfaction with the type of illness". "I would like to treat my patients like they do. Their regular presence at the clinic." "I was interested in everything about them. They are my role models, both in their professional ethics and in their educational role".

Discussion

Medical science professors are a key element in medical ethics education, as they can shape the moral and professional character of students. This study aimed to explain the role of the hidden curriculum in shaping professional ethics by examining the experiences of medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. From the interviews, a total of 188 open codes were identified. By merging codes with similar themes during the axial coding stage, a total of 36 axial codes, or subthemes, were generated. In the third stage, the researcher obtained categories for the six main themes.

The first main theme obtained from the data analysis was "modeling professional ethics from the teaching and behavior of professors directly and indirectly." This theme included six categories of subthemes, including "Negative moral patterns, professors' behavior with patients, professors' personality, professors' positive behavior, professors' training, and interactions." In line with these results, studies have shown that personal factors, including individual characteristics, as well as interpersonal and environmental factors, play a role in the professional ethics of doctors. Furthermore, students tend to emulate what their professors do rather than what they say [25]. This suggests that the impact of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum. Some studies show that, just as professors’ deal with students, students will also deal with their patients, colleagues, and future students. Therefore, students model the behavior of their teachers. Of course, this modeling occurs in both positive and negative ways. In any case, medical students receive both positive and negative messages from the clinical environment during their internship period [14, 15]. The second main theme obtained was "modeling professional ethics from society and people other than professors." This main theme had subthemes including: "Ethical observance is rooted in family and school, discrimination and favoritism play a negative role model, the foundations of morality in family and friends, role modeling from peers, role modeling outside the educational environment." In line with the results of this study, some studies have found that friends and family members influence students when it comes to learning medical ethics. Most of them believe that the influence of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum [16]. The third theme obtained was "modeling positive or negative professional ethics under the influence of circumstances." This main theme included subthemes, categorized as follows: "conditions that hurt role modeling," "the presence of special conditions affecting role modeling," "the role of negative reinforcement in role modeling," and "the influence of moral role models on economic status." In some studies, students reported that learning medical ethics is influenced by individual factors, such as self-efficacy and moral competence, which affect their professional growth and motivation to cooperate with members of the therapy team in improving their competence and clinical performance [26]. According to the findings, having proper communication as well as having an encouragement and support system and having specific rules facilitating professionalism and the inadequacies of the organizational and management system of the Ministry of Health and the educational system and not paying attention to the hidden curriculum in the transfer of professionalism characteristics, is one of the obstacles of professionalism. The fourth main theme included "Motivation for modeling professional ethics by students." This theme included four subthemes categories: "tendency to identify with professors," "the role of advertising in professional ethics," "general acceptability of the role model," and "students' tendency to imitate the teacher's behavior." In line with the results of this study, the research demonstrated that the willingness to cooperate with members of the treatment team is effective in enhancing the competence and clinical performance of students. Burgess et al. showed that students imitate the characteristics and behaviors they aspire to have as doctors in the future [9]. Some professors possess characteristics that motivate students to aspire to be role models. On the other hand, some professors lack these characteristics, and students have no motivation to imitate their behavior. In any case, the student must follow the model and emulate the model's behavior. Therefore, having the motivation and intention for this work has a great impact on the role model of students [27]. The fifth main theme included "Beliefs in having inherent capabilities in modeling professional ethics." This main theme consists of five subthemes c: "Belief in the innateness of morality," "The spirituality of religious beliefs are modeled, "Sacrifice and self-sacrifice are modeled, "The lack of influence of education on moral modeling," and "Positive modeling of negative behavior." In line with this finding, looking at the research conducted on the components of professors' professional ethics, it shows that some components, such as the acceptance of different cultural and religious contexts, affect modeling the role of professional ethics [8]. Therefore, the inherent characteristics of students play a role in modeling. Due to this process, an optimal model may be obtained from inappropriate behavior, and conversely, a negative model may be derived from positive behavior. The proverb "Learning politeness from rude people" can be an example of this issue. The sixth main theme identified was "characteristics of professors who model professional ethics." This main theme consists of seven categories: "the level of literacy and knowledge of professors becomes a role model," "helping people is a good role model," "the well-groomed appearance of professors becomes a role model," teachers who are agents themselves become role models," "They are humble role models," "Professors are role models, they are strict," "Helping the patient is a good role model." This topic refers to the process of role modeling by students from professors. For this reason, the influence of clinical environments is greater than that of the formal education curriculum every day. Some of the characteristics that are modeled include specialized competence, recognition of comprehensive dimensions, standard evaluation, adherence to organizational rules, and appropriate interaction with colleagues. Moreover, the most important characteristic of an exemplary professor from the student's point of view is "mastery of the professor and general knowledge is mentioned about the subject being taught [28, 29]. In contrast to the findings of this study, the determination and strictness of professors were identified as the least important characteristics. Additionally, the presentation of engaging course material, the professor's fluency, a close relationship between the professor and students, and appropriate eye contact were also noted as qualities of effective professors. [26]. Lempp and Seale and Safari et al. introduced professors as role models who have been encouraging and motivating roles for them. The commitment and adherence of these professors to teaching and communicating with students, patients, and colleagues are exemplary [30, 31]. As is known, while some of the components expressed in studies on the characteristics of model professors are consistent with the results of the present study, others differ. This is due to the difference in the goals of these studies. This means that some studies focus on individual factors, some on social factors, and some on organizational factors.

The data collection method used in this study was interviews, which come with their limitations. This study was no exception; for example, individual differences among participants may have influenced the rate at which they responded to the interview questions. Therefore, it should be expected that the findings of this study cover all the components of professional ethics. However, many studies confirm the results of this study. In conclusion, it is important to emphasize that, given the significance of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics, it is essential to create conducive conditions for modeling and to take steps toward establishing a healthy environment. Additionally, fostering an appealing atmosphere that encourages the modeling of positive behaviors is necessary. It is recommended to incorporate aspects of professional ethics into the selection of medical students. According to the study's researchers, medical professors need to view themselves as obligated to instill the professional ethics of being a doctor in their students while teaching the fundamental concepts of medical ethics. In addition to imparting medical skills, they should also prioritize teaching medical ethics to both current students and future doctors.

Conclusion

The findings revealed six main themes related to the role of the hidden curriculum in modeling professional ethics. These themes include "direct and indirect modeling," "modeling from society," "modeling under the influence of circumstances," "the necessity of motivation for modeling," "belief in inherent capabilities for modeling," and "characteristics of teachers as models of professional ethics." According to the results of this study, clinical professors play a significant role as role models for students in developing professional ethics. It is crucial to improve educational environments, encourage teachers to be mindful of their behavior in clinical settings, create appropriate modeling opportunities, and increase the number of professors who can serve as role models in professional ethics.

Ethical considerations

To uphold ethical considerations, participation in the study was voluntary, and participants had the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. As mentioned, informed consent was obtained from participants, and the instruments contained no personally identifiable information and were coded to ensure that the participants answered voluntarily and freely. The study was registered and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virtual University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.VUMS.REC.1399.007).

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

No artificial intelligence was utilized in writing this article.

Acknowledgment

The participants in this study were final-year medicine students at the internship level, and we hereby thank all of them. This article is extracted from the master's thesis in the field of medical education at the Virtual University of Medical Sciences in Iran.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the work.

Funding

The article was written without any financial support.

Data availability statement

The data is available and can be provided to the editor or other responsible individuals at any time. For access, please contact the corresponding author at: ysafari79@yahoo.com.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2024/12/27 | Accepted: 2025/06/23 | Published: 2025/07/13

Received: 2024/12/27 | Accepted: 2025/06/23 | Published: 2025/07/13

References

1. Kumar Ghosh S, Kumar A. Building professionalism in human dissection room as a component of hidden curriculum delivery: a systematic review of good practices. Anatomical Sciences Education. 2019;12(2):210–221 [DOI]

2. Polmear MRA. Faculty perspectives and practices related to engineering ethics and societal impacts education [dissertation]. ProQuest LLC; 2019. [DOI]

3. dissertation]. ProQuest LLC; 2019. [https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2--30510]

3. Orón Semper JV, Blasco M. Revealing the hidden curriculum in higher education. Studies in Philosophy and Education. 2018;37:481–498. [DOI]

4. Seidel VP, Marion TJ, Fixson SK. Innovating how to learn design thinking, making, and innovation: incorporating multiple modes in teaching the innovation process. Informs Transactions on Education. 2020;20(2):73–84. [DOI]

5. Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2019;8(2):90–97 [DOI]

6. Higashi RT, Tillack A, Steinman MA, Johnston CB, Harper GM. The ‘worthy’ patient: rethinking the ‘hidden curriculum’ in medical education. Anthropology & Medicine. 2013;20(1):13–23. [DOI]

7. Li H. The significance and development approaches of hidden curriculum in college English teaching. In: proceedings of the 3rd international seminar on education innovation and economic management (SEIEM 2018). Atlantis Press; 2019. [DOI]

8. Jayasuriya-Illesinghe V, Nazeer I, Athauda L, Perera J. Role mod els and teachers: medical students' perception of teaching-learning methods in clinical settings, a qualitative study from Sri Lanka. BMC Medical Education. 2016;16(1):1–8. [DOI]

9. Burgess A, Goulston K, Oates K. Role modelling of clinical tutors: a focus group study among medical students. BMC Medical Education. 2015;15(1):1–9 [DOI]

10. Thulesius HO, Sallin K, Lynoe N, Löfmark R. Proximity morality in medical school – medical students forming physician morality "on the job": grounded theory analysis of a student survey. BMC Medical Education. 2007;7:1–6. [DOI]

11. de Lemos Tavares AC, Travassos AG, Tavares RD, Rêgo MF, Nunes RM. Teaching of ethics in medical undergraduate programs. Acta Bioethica. 2021;27(1). [DOI]

12. de Lemos Tavares AC, Travassos AG, Tavares RD, Rêgo MF, Nunes RM. Teaching of ethics in medical undergraduate programs. Acta Bioethica. 2021;27(1):101–117 [DOI]

13. Sullivan BT, DeFoor MT, Hwang B, Flowers WJ, Strong W. A novel peer-directed curriculum to enhance medical ethics training for medical students: a single-institution experience. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development. 2020;7:2382120519899148. [DOI]

14. Garza de la S, Phuoc V, Throneberry S, Blumenthal-Barby J, McCullough L, Coverdale J. Teaching medical ethics in graduate and undergraduate medical education: a systematic review of effectiveness. Academic Psychiatry. 2017;41:520–525. [DOI]

15. Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME Guide No. 27. Medical Teacher. 2013;35(9):e1422–e1436 [DOI]

16. Obeidi N, Motamed N. Comparison of students' and teachers' viewpoints about clinical education environment: a study in paramedical and nursing midwifery schools of Bushehr university of medical sciences. Strides in Development of Medical Education. 2011;8(1):88–89 [DOI]

17. Yadav H, Jegasothy R, Ramakrishnappa S, Mohanraj J, Senan P. Unethical behavior and professionalism among medical students in a private medical university in Malaysia. BMC Medical Education. 2019;19(1):1–5. [DOI]

18. Doja A, Bould MD, Clarkin C, Eady K, Sutherland S, Writer H. The hidden and informal curriculum across the continuum of training: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Medical Teacher. 2016;38(4):410–418. [DOI]

19. Raso A, Marchetti A, D'Angelo D, et al. The hidden curriculum in nursing education: a scoping study. Medical Education. 2019;53(10):989–1002. [DOI]

20. Safari Y, Khatony A, Khodamoradi E, Rezaei M. The role of hidden curriculum in the formation of professional ethics in Iranian medical students: a qualitative study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2020;9:172. [DOI]

21. Mohajan HK. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People. 2018;7(1):23–48 [DOI]

22. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015;42:533–544. [DOI]

23. Rayray PS, Bagarra CA, Bermudez SC, Galvez ME, Javier MY, Villarama J. Phenomenological study on the impact of resumption of in-person classes on the learning attitudes of laboratory school learners. Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2024;21(8):927–937.

24. Yamani N, Liaghatdar MJ, Changiz T, Adibi P. How do medical students learn professionalism during clinical education? A qualitative study of faculty members' and interns' experiences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2010;9(4). [DOI]

25. Safari Y, Yoosefpour N. Evaluating the relationship between clinical competence and clinical self-efficacy of nursing students in Kermanshah university of medical sciences. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development. 2017;8:380–385. [DOI]

26. Lynoe N, Löfmark R, Thulesius H. Teaching medical ethics: what is the impact of role models? Some experiences from Swedish medical schools. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2008;34(4):315–316. [DOI]

27. Gholampour M, Pourshafei H, Farasatkhah M, Ayati M. Components of teachers’ professional ethics: a systematic review based on Wright’s model. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 2020;15(58):145–174. [DOI]

28. Joynt GM, Wong WT, Ling L, Lee A. Medical students and professionalism – do the hidden curriculum and current role models fail our future doctors? Medical Teacher. 2018;40(4):395–399. [DOI]

29. Safari, Y., Yoosefpour, N. Dataset for assessing the professional ethics of teaching by medical teachers from the perspective of students in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Iran (2017). Data in Brief, 2018:20, 1955-1959. [DOI]

30. Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students' perceptions of teaching. The British Medical Journal. 2004;329(7469):770–773. [DOI]

31. Safari Y, Khatony A, Tohidnia MR. The Hidden Curriculum Challenges in Learning Professional Ethics Among Iranian Medical Students: A Qualitative Study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:673-681 [DOI]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |