Mon, Feb 23, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 4 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(4): 63-72 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: COE No. 249/2023 IRB No. P3-0104/2566

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Srisingh K, Jeephet K. Student views of a flipped classroom and case-based learning session informed by the PERMA well-being model: a pilot study among fourth-year medical students. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (4) :63-72

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2555-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2555-en.html

1- Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, 65000, Thailand , klaitas@nu.ac.th

2- Research Center of the Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, 65000, Thailand

2- Research Center of the Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, 65000, Thailand

Full-Text [PDF 561 kb]

(168 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (556 Views)

Full-Text: (23 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: We wanted to see how fourth-year medical students felt about a new teaching approach we created—combining flipped classroom and case-based learning with a focus on student well-being through the Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment (PERMA) model.

Materials & Methods: Twenty-two fourth-year medical students participated in our study between June 1, 2023, to April 30, 2024. Here's how it worked: students first watched instructional videos at home over two weeks. When they came to class, they took a quick quiz, then dove into discussing case study videos using the PERMA framework. We asked students to share their thoughts right after the session and again a month later to see how their perspectives held up over time.

Results: About one-third of our participants were male (7 out of 22), with an average age of 23. Students scored well on both the pre-test (8.18 out of 10) and post-test (8.77 out of 10), though the improvement wasn't statistically significant. The good news? Students were highly satisfied with the experience, and their enthusiasm didn't fade—their satisfaction scores remained consistently high both immediately after and a month later (4.41 vs 4.55 out of 5 for knowledge comprehension and around 4.00 for overall satisfaction). We saw small improvements in self-directed learning, memory, critical thinking, teamwork, and patient management skills, though learning motivation stayed about the same. Interestingly, students felt more confident using their knowledge and assessing lung sounds as time went on. Video engagement remained high, and stress levels didn't increase—which was encouraging.

Conclusion: Our pilot study shows that medical students really engaged with and appreciated this PERMA-based flipped classroom approach. While we didn't see dramatic jumps in test scores or other measured outcomes, students clearly found the method valuable and feasible. These findings provide valuable preliminary insights and will inform the design of a larger, more comprehensive study to evaluate the approach’s full education impact.

Introduction

Note: The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Each evaluation item was prefaced with the phrase "This teaching model…". Data on participants' age and gender were also collected.

Tools/Instruments

The study used an online questionnaire (Table 1), adjusted from a study by Li Cai et al. [12] to check students' views of the learning intervention. The instrument had 12 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). In the original study, the questionnaire showed good reliability, with a reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.85, showing high internal consistency.

Content validity had been previously set up through expert review to ensure the items were related to the educational context.

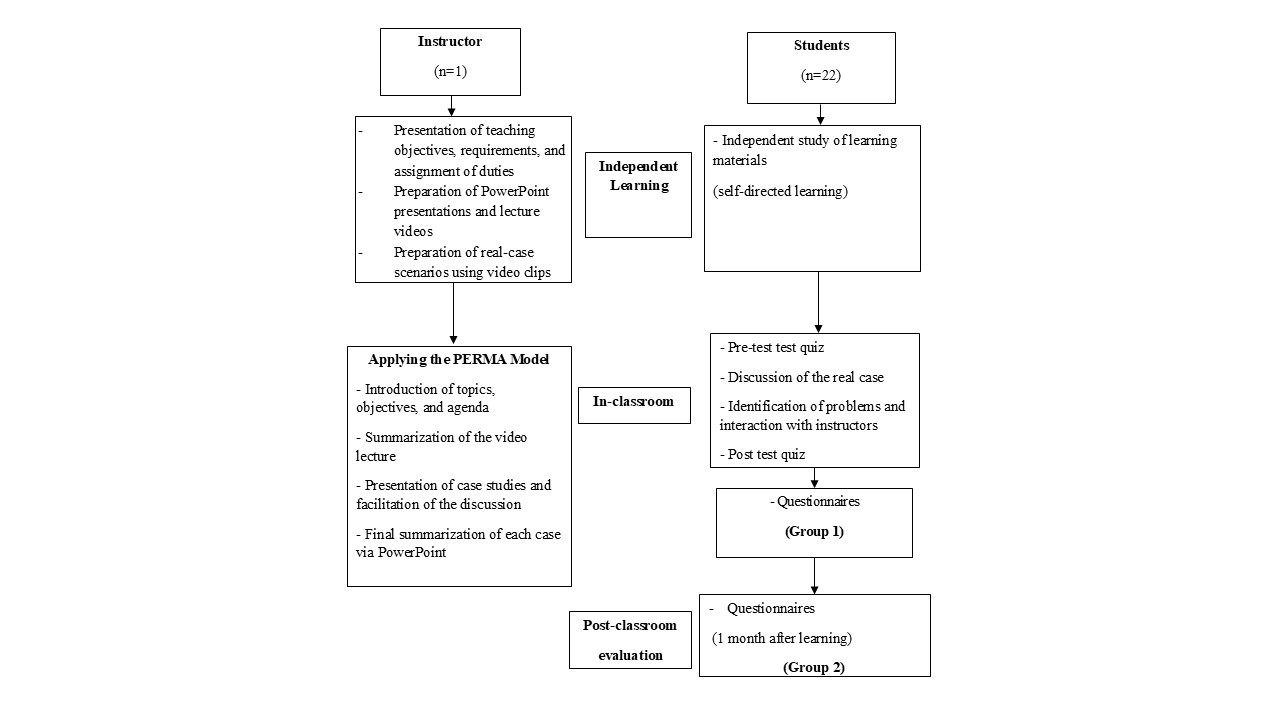

In the present study, the questionnaire was adjusted to include demographic information such as age and gender, in addition to the 12 evaluation items (Table 1). The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. To ensure content validity in the current context, the adjusted instrument was reviewed by three experts in the field. The Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) values ranged from 0.67 to 1.00. Specifically, Items 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, and 11 received an IOC score of 0.67, while Items 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, and 12 received an IOC score of 1.00. These results show that the items were generally appropriate and matched the research goals.

Revisions were made based on expert feedback to improve item clarity and contextual relevance. Before the main data collection, a pilot test was done with 10 students who shared similar characteristics with the target population to check the reliability of the adjusted instrument. The internal consistency of the questionnaire, determined using Cronbach's alpha, which was 0.95, showing a high level of reliability.

Data collection methods

The study design included classroom activities within a flipped classroom and case-based learning model for fourth-year medical students. This included research-curated teaching videos, along with dedicated case study videos that encouraged discussions on patient diagnoses, investigations, pathophysiology, treatment, and potential complications. Initially, the course plan was developed based on the approved medical curriculum from the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME). Then, topics within the course content were selected based on the reference text and added to with current research articles. Content delivery included in-classroom PowerPoint presentations and video recordings of prior lectures by the instructor. These videos were initially uploaded to the University website via the Medical Knowledge Center of MedNU and then made available for download for the current classes. Additionally, the instructor prepared recordings of various case studies, ensuring informed consent was gotten from all patients and parents involved. The case studies featured in the videos included patient visits to the outpatient pediatric clinic and inpatient admissions to the pediatric ward. The video content provided a complete demonstration of clinical history taking, systematic and thorough physical examination across all major body systems, and the collection of related clinical data. This included detailed assessments of general appearance, as well as focused examinations of the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat, in addition to the cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal, neurological, and musculoskeletal systems. Two weeks before the start of classroom activity, students were introduced to the course as well as the teaching and learning approach. Home learning activities, including videos (e-learning) of previous lectures by the instructor available on the University website, were also assigned and explained. At the beginning of the classroom activity, a pre-test was given to all students, with a maximum score of 10 points.

The pre-test consisted of 10 questions designed to check the students' prior knowledge, and scoring guidelines were explained in advance. Students who scored 5 or below were identified as potentially needing additional support to improve their understanding and engagement with the video content. Rather than being excluded, these students were encouraged to review the materials more thoroughly and were provided extra resources and guidance as needed. No student was excluded based on pre-test performance.

Following the pre-test, the instructor carried out classroom activities guided by the PERMA mode (Table 2). Although the PERMA well-being model served as the conceptual framework for instructional design, this study focused on checking students' satisfaction and views of their learning experience rather than measuring well-being outcomes directly. The facilitator was briefed and trained in advance on how to apply the PERMA framework to session design. This included summarizing the video content and presenting case-base videos materials to encourage in-depth classroom discussions. During the six-hour classroom session, students and the instructor worked together to analyze each case, clarified misconceptions, and looked into related topics. The instructor mainly acted as a facilitator, encouraging active taking part and inquiry. Discussions went beyond the case materials to include additional topics raised by students, such as lung sound auscultation and identification. The session ended with a PowerPoint presentation reinforcing key concepts and providing extra foundational knowledge and clinical diagnostic considerations. At the end of the 6-hours classroom session, the 22 students took a post-test quiz consisting of the 10 questions. This post-test was given to check short-term knowledge retention.

The students then completed an online questionnaire via Google Forms right away after the session (T1), and again one month later (T2) to check long-term satisfaction with the teaching model and knowledge retention, enabling comparison with their initial answers (Figure 1).

Table 2. Educational activities and their intended objectives

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Means and Standard Deviations (SD) were calculated for continuous variables, while and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables such as age and gender.

The normality of continuous variables, including aggregated Likert-scale scores, was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of Q–Q plots. The results showed no big deviation from a normal distribution; therefore, parametric tests were deemed appropriate for later analyses.

Paired samples t-tests were done to compare pre- and post-intervention scores on self-perceived competence and satisfaction.

Although Likert-scale data are ordinal in nature, the aggregated scores came close to continuous, normally distributed variables, supporting the use of parametric methods.

Future studies may consider complementary non-parametric analyses to confirm these findings. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Of the 22 students taking part, 7 were male (31.8%). The mean age was 23 years. The result showed a mean pre-test score of 8.18 ± 1.59 points and a post-test score of 8.77 ± 1.11 points, showing no big difference (p = 0.114).

The Google Forms questionnaire, checking students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction with the learning model, was completed by all students, with a response rate of 100%. With a maximum response score of 5, students expressed agreement with the teaching model. The researcher observed that most students were actively engaged in classroom activities and discussions related to the case studies and there were no signs of disengagement or boredom among them. Students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction were checked at two time points: right away after the classroom session (T1) and one month later (T2). No statistically big difference was observed in learning motivation between T1 and T2 (T1: 4.23 ± 0.81; T2: 4.55 ± 0.67; p = 0.184). Descriptive comparisons suggested slight improvements over time in self-directed learning (T1: 4.41 ± 0.73; T2: 4.45 ± 0.74; p = 0.840), memory retention (T1: 4.23 ± 0.81; T2: 4.41 ± 0.73; p = 0.446), and critical thinking skills (T1: 4.09 ± 0.92; T2: 4.41 ± 0.80; p = 0.201), although these differences were not statistically big.

Similarly, while not statistically big, students at T2 reported marginally higher scores in perceived patient management abilities (T1: 4.23 ± 0.69; T2: 4.36 ± 0.79; p = 0.525) and teamwork skills (T1: 3.82 ± 0.91; T2: 4.09 ± 0.92; p = 0.300).

They showed slightly greater confidence in applying knowledge to patient care (T1: 4.41 ± 0.73; T2: 4.91 ± 0.59; p = 1.000) and modest improvement in lung sound assessment skills (T1: 4.32 ± 0.65; T2: 4.50 ± 0.80; p = 0.383), a core competency in pulmonary diagnosis.

Overall satisfaction with the learning model stayed consistently high across both time points, (T1: 3.77 ± 1.15; T2: 3.86 ± 1.24; p = 0.790).

Self-reported understanding of the content was identical between the two groups (T1: 4.41 ± 0.67; T2: 4.55 ± 0.74; p = 0.561), and stress levels related to classroom activities were comparable (T1: 3.55 ± 1.41; T2: 3.64 ± 1.26; p = 0.851). Interestingly, students at T2 reported greater diligence in watching the instructional videos than those at T1, although this difference was not statistically big (T1: 4.05 ± 0.79; T2: 4.36 ± 0.85; p = 0.167) (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction scores between two time points

Note: Data presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation. T1: First survey time point, T2: Second survey time point.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; Sig. statistical significance; p, probability value.

Discussion

Overall, students reported high levels of satisfaction with the teaching model, with the highest-rated aspect being the perceived benefit to their learning and knowledge understanding. In contrast, the lowest ratings were related to stress levels, suggesting that the model did not cause big stress. These findings show that the combination of the FC and Case-Based Learning (CBL) approaches within the PERMA model of well-being contributed to a positive, low-stress learning experience, that improved understanding and engagement.

All questionnaire items received mean scores of four or higher, reflecting strong student approval of the teaching approach. The highest-rated items highlighted perceived improvements in knowledge understanding, self-directed learning, and the application of knowledge in clinical contexts. These findings match previous studies showing that FC and other active learning strategies help deeper learning, motivation, and clinical reasoning skills in medical education [12, 15].

One reason for these results could be that the FC approach frees up cognitive resources for higher-order thinking during in-class activities by letting students study foundational material on their own before class. The focus on self-directed learning aligns with critical skills in clinical practice, where students must solve problems independently and make well-informed decisions. This approach might better prepare students for patient care duties by fostering these abilities in a controlled, cooperative setting.

Despite the requirement that students watch lectures on tape before participating in class activities, some students expressed less interest in the pre-course materials. Clinical workload, time constraints, and limited access to dependable technology were the main obstacles found. The effectiveness of flipped learning models may be hampered by these difficulties, which are a reflection of larger structural problems, especially in medical education settings where students must juggle clinical and academic obligations.

Prior research on the shortcomings of the flipped classroom approach has identified similar problems [24, 32–34]. For example, since discussions and case analyses depend on prior knowledge, the benefits of in-class learning are diminished when students are unable to sufficiently prepare before class. Under such circumstances, the flipped model's active learning element might lose its significance or even work against you. Therefore, these findings emphasize the need for better institutional mechanisms, such as protected learning time, improved technological infrastructure, and strategies to encourage equitable access to pre-class materials.

It is possible that some students prioritized meeting the minimum preparation requirement rather than fully engaging with the video, reflecting a surface-level or strategic learning approach driven by time constraints. Previous study reporting higher engagement levels often involved student cohorts with fewer competing obligations or better institutional support [35]. This suggests that while preparatory assessments may encourage compliance, they do not necessarily guarantee meaningful engagement. In order to support deeper learning, future research could examine complementary techniques like reflective prompts or in-class application tasks.

There were no statistically significant differences in mean scores between the Google Forms questionnaire responses at T1 (shortly after the intervention) and T2 (one month later). According to this research, the teaching approach resulted in long-term satisfaction and perceived learning advantages in addition to instant favorable opinions. The consistency of scores across time points shows that students continued to value the learning experience even after the initial exposure, reflecting the lasting impact of the instructional design.

These results match prior studies showing that active learning strategies, such as case-based and problem-based learning, improve both satisfaction and academic performance [12, 14, 15, 36]. However, in contrast to the majority of earlier research, this study reexamined student opinions one month later, enabling evaluation of long-term impacts. The PERMA well-being framework may have contributed to longer-term satisfaction by fostering emotional engagement and a sense of purpose, as indicated by the consistently high ratings.

The difference did not reach statistical significance, even though post-test scores were marginally higher than pre-test scores. This might be because there were only ten test items, which decreased the assessment's sensitivity to pick up on minute learning gains. The short interval between pre- and post-tests may also have limited the opportunity for deeper cognitive combination of the material. Additionally, the test items may have emphasized surface-level recall rather than higher-order thinking, which may not fully capture the outcomes associated with FC and CBL approaches. Future studies should consider developing more complete and confirmed assessments—ideally including application-based or problem-solving items—to better check learning outcomes in active learning environments.

The teaching model was designed based on the PERMA framework to help student well-being during classroom activities. Specifically, it aimed to grow positive emotions by creating enjoyable learning experiences and encouraging open communication, thereby improving engagement. Case-based discussions helped meaningful relationships among peers, while supportive instructor interactions contributed to positive emotional experiences. Students were able to connect theoretical ideas to real-world application through the use of authentic clinical scenarios, which gave the content purpose and significance. By aligning activities with individual learning objectives and promoting reflection on skill development and mastery, the model also promoted achievement.

However, empirical data directly measuring changes in students' well-being across the PERMA dimensions were not collected for this study. Therefore, even though the PERMA framework served as the foundation for the instructional design, its effect on wellbeing remains theoretical in this study. To offer empirical proof of the model's impact on students' well-being, future research should incorporate validated metrics of PERMA-related outcomes.

It is important to recognize the various limitations of this study. First, the sample size was small, which could limit the findings' generalizability and statistical power. Second, the study was conducted in a single location, which limited the results' generalizability to other organizations or situations.

Third, it is more difficult to make causal conclusions regarding the efficacy of the teaching model when there is no control group. Furthermore, it's possible that the limited number of questions in the pre- and post-tests made it more difficult to identify significant gains in knowledge. To increase the validity of the results, future research should think about utilizing a wider range of assessment tools. Last but not least, implementing this teaching model required extensive instructor preparation, especially for creating and integrating case-based video resources. Even though students were very satisfied, the demands of the instruction might make wider adoption difficult. Implementation this teaching model could be gradually integrated into existing medical curricula as a supplemental or elective learning module. Educators can apply the PERMA framework to design learning environments that enhance student well-being alongside academic performance, particularly in areas such as self-directed learning, teamwork, and reflective practice. Future large-scale studies should explore how this approach can be optimized across different disciplines, cohorts, and cultural contexts, as well as assess its long-term effects on knowledge retention, clinical reasoning, and professional development.

Establishing institutional support and faculty development programs will be critical for sustainable implementation and broader adoption.

Conclusion

This pilot study examined the implementation of a flipped classroom and case-based learning model informed by the PERMA framework among small groups of fourth-year medical students.

Although no statistically big differences were observed between pre- and post-test scores, students reported high levels of satisfaction and engagement.

These findings show that combining the PERMA framework with active learning strategies may provide a supportive and effective educational environment. Further studies with larger samples and more rigorous designs are warranted to confirm these results and look into the model's broader impact on learning outcomes and student well-being.

Ethical considerations

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the University. Additionally, verbal informed consent was gotten from the students taking part.

The study followed established ethical principles and institutional guidelines throughout. The code for the approved work was COE No. 249/2023 IRB No. P3-0104/2566.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

To enhance linguistic clarity and stylistic consistency, artificial intelligence (AI)-based grammar and language refinement tools were utilized during manuscript preparation.

This process aimed to produce a polished academic text that meets the linguistic standards expected in high-impact international journals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Miss Daisy Gonzales from the International Relations Section, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University for her valuable help in editing the manuscript.

A special acknowledgment also to Mr. Roy I. Morien of the Naresuan University Graduate School for his editing of the grammar, syntax and general English expression in this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Assoc.Prof. Klaita Srisingh reviewed the literature, designed the study, developed the methodological frame work for the study, performed data collection and data analysis, wrote the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

Ms. Kornthip Jeephet developed the methodological frame work for the study, performed data collection and data analysis, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding received for the study.

Data availability statement

The data that support of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research students but are available from the corresponding author (K.S.) upon reasonable request.

Background & Objective: We wanted to see how fourth-year medical students felt about a new teaching approach we created—combining flipped classroom and case-based learning with a focus on student well-being through the Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment (PERMA) model.

Materials & Methods: Twenty-two fourth-year medical students participated in our study between June 1, 2023, to April 30, 2024. Here's how it worked: students first watched instructional videos at home over two weeks. When they came to class, they took a quick quiz, then dove into discussing case study videos using the PERMA framework. We asked students to share their thoughts right after the session and again a month later to see how their perspectives held up over time.

Results: About one-third of our participants were male (7 out of 22), with an average age of 23. Students scored well on both the pre-test (8.18 out of 10) and post-test (8.77 out of 10), though the improvement wasn't statistically significant. The good news? Students were highly satisfied with the experience, and their enthusiasm didn't fade—their satisfaction scores remained consistently high both immediately after and a month later (4.41 vs 4.55 out of 5 for knowledge comprehension and around 4.00 for overall satisfaction). We saw small improvements in self-directed learning, memory, critical thinking, teamwork, and patient management skills, though learning motivation stayed about the same. Interestingly, students felt more confident using their knowledge and assessing lung sounds as time went on. Video engagement remained high, and stress levels didn't increase—which was encouraging.

Conclusion: Our pilot study shows that medical students really engaged with and appreciated this PERMA-based flipped classroom approach. While we didn't see dramatic jumps in test scores or other measured outcomes, students clearly found the method valuable and feasible. These findings provide valuable preliminary insights and will inform the design of a larger, more comprehensive study to evaluate the approach’s full education impact.

Introduction

To manage the complexity of clinical practice, which entails making important decisions and collaborating with multidisciplinary teams, medical professionals require advanced knowledge, critical thinking, and transformative skills. As a result, medical programs are made to equip students with professional skills prior to clinical training [1–3]. With instructional strategies that adapt to the changing needs of medical education, educational systems should support students who are able to thrive in challenging healthcare environments. The combination of digital technology into medical education has the potential to improve learning outcomes and better prepare students for contemporary clinical settings [4–6].

Instead of concentrating solely on the treatment of mental illness, Martin Seligman's [7] theory of positive psychology places an emphasis on comprehending and assisting the positive aspects of human experience. A key idea in Seligman's earlier research is "learned helplessness," which postulates that people can become passive and disengaged as a result of repeatedly experiencing failure or helplessness. His later work in positive psychology, on the other hand, emphasizes the value of developing positive emotions, character traits, and personal strengths in order to enhance general well-being.

A key component of Seligman's model is the Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment (PERMA) framework, which lists five essential components of well-being: (a) Positive Emotion, which includes experiencing joy, gratitude, and other positive emotions; (b) Engagement, which is defined as deeply immersing oneself in challenging and meaningful activities; (c) Relationships, which emphasizes the importance of meaningful and supportive social connections; (d) Meaning, which is defined as having a sense of purpose and contributing to something bigger than oneself; and (e) Accomplishment, which is the pursuit and achievement of goals that contribute to a sense of fulfillment and achievement.

Seligman's work encourages individuals and institutions to focus on these elements to encourage a more balanced, fulfilling, and resilient life. A literature review supports the effectiveness of the Flipped Classroom (FC) model across various health sciences education domains, including physiology, anatomy, pathology, nephrology, endocrinology, hematology, primary care, and other subjects [10–15]. FC, a popular model for active and student-centered learning, inverts the traditional learning process by shifting learning activities from the classroom to home, transforming homework into in-classroom activities based on prior home learning [16].

Previous studies show that the FC model encourages peer-helped learning, collaborative learning, and critical thinking, improving student performance, motivation, and satisfaction [17–20]. However, FC has limitations, such as inadequate student preparation before class, lack of support during home learning and instructors' inability to monitor student progress during that phase.

Additionally, both students and teachers see this approach as time-consuming and demanding [21–25].

FC includes a wide range of in-class activities, including discussions, small group activities, feedback, problem-solving and Question-and-Answer (Q&A) sessions, collaborative group work, case studies, hands-on experiments, quizzes, student presentations, instructor-helped assignments, educational games, microlectures, group projects, concept mapping, and brainstorming [18, 21, 26–29].

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This quasi-experimental study was done at Naresuan University Hospital, a tertiary care teaching hospital in northern Thailand, between June 1, 2023 and April 30, 2024. The Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, admits about 170–175 students annually. During the preclinical phase (Years 1–3), all students study at the main university campus. In the clinical years (Years 4–6), students are assigned to one of six affiliated teaching hospitals. Naresuan University Hospital, as a major clinical training site, accommodates about 30 students per year. In the fourth year, students rotate through core clinical disciplines: Internal Medicine (3 months), Surgery (3 months), Pediatrics (2 months), Obstetrics and Gynecology (2 months), and Psychiatry (1 month). The remaining time is dedicated to medical research and Health System Science, ensuring a complete foundation in both clinical practice and healthcare systems.

Participants and sampling

All 22 fourth-year medical students who completed their pediatric rotation at Naresuan University Hospital during the 2023 academic year were included in the study. These students took part in their clinical rotations in small groups of about 4–5 students, rotating every three months throughout the study period.

The pediatric curriculum included theoretical instruction on various aspects of pediatric care.

For the purposes of this study, the lecture content specifically focused on upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses, delivered over a total of six teaching hours.

Following the lecture series, all 22 students completed an online questionnaire via Google Forms (T1), and were checked again one month later (T2) to check knowledge learning as well as short- and long-term knowledge retention.

The questionnaire also measured student satisfaction with the flipped classroom and case-based learning model (Table 1).

Instead of concentrating solely on the treatment of mental illness, Martin Seligman's [7] theory of positive psychology places an emphasis on comprehending and assisting the positive aspects of human experience. A key idea in Seligman's earlier research is "learned helplessness," which postulates that people can become passive and disengaged as a result of repeatedly experiencing failure or helplessness. His later work in positive psychology, on the other hand, emphasizes the value of developing positive emotions, character traits, and personal strengths in order to enhance general well-being.

A key component of Seligman's model is the Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment (PERMA) framework, which lists five essential components of well-being: (a) Positive Emotion, which includes experiencing joy, gratitude, and other positive emotions; (b) Engagement, which is defined as deeply immersing oneself in challenging and meaningful activities; (c) Relationships, which emphasizes the importance of meaningful and supportive social connections; (d) Meaning, which is defined as having a sense of purpose and contributing to something bigger than oneself; and (e) Accomplishment, which is the pursuit and achievement of goals that contribute to a sense of fulfillment and achievement.

Seligman's work encourages individuals and institutions to focus on these elements to encourage a more balanced, fulfilling, and resilient life. A literature review supports the effectiveness of the Flipped Classroom (FC) model across various health sciences education domains, including physiology, anatomy, pathology, nephrology, endocrinology, hematology, primary care, and other subjects [10–15]. FC, a popular model for active and student-centered learning, inverts the traditional learning process by shifting learning activities from the classroom to home, transforming homework into in-classroom activities based on prior home learning [16].

Previous studies show that the FC model encourages peer-helped learning, collaborative learning, and critical thinking, improving student performance, motivation, and satisfaction [17–20]. However, FC has limitations, such as inadequate student preparation before class, lack of support during home learning and instructors' inability to monitor student progress during that phase.

Additionally, both students and teachers see this approach as time-consuming and demanding [21–25].

FC includes a wide range of in-class activities, including discussions, small group activities, feedback, problem-solving and Question-and-Answer (Q&A) sessions, collaborative group work, case studies, hands-on experiments, quizzes, student presentations, instructor-helped assignments, educational games, microlectures, group projects, concept mapping, and brainstorming [18, 21, 26–29].

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This quasi-experimental study was done at Naresuan University Hospital, a tertiary care teaching hospital in northern Thailand, between June 1, 2023 and April 30, 2024. The Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, admits about 170–175 students annually. During the preclinical phase (Years 1–3), all students study at the main university campus. In the clinical years (Years 4–6), students are assigned to one of six affiliated teaching hospitals. Naresuan University Hospital, as a major clinical training site, accommodates about 30 students per year. In the fourth year, students rotate through core clinical disciplines: Internal Medicine (3 months), Surgery (3 months), Pediatrics (2 months), Obstetrics and Gynecology (2 months), and Psychiatry (1 month). The remaining time is dedicated to medical research and Health System Science, ensuring a complete foundation in both clinical practice and healthcare systems.

Participants and sampling

All 22 fourth-year medical students who completed their pediatric rotation at Naresuan University Hospital during the 2023 academic year were included in the study. These students took part in their clinical rotations in small groups of about 4–5 students, rotating every three months throughout the study period.

The pediatric curriculum included theoretical instruction on various aspects of pediatric care.

For the purposes of this study, the lecture content specifically focused on upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses, delivered over a total of six teaching hours.

Following the lecture series, all 22 students completed an online questionnaire via Google Forms (T1), and were checked again one month later (T2) to check knowledge learning as well as short- and long-term knowledge retention.

The questionnaire also measured student satisfaction with the flipped classroom and case-based learning model (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants' evaluation of the teaching model using a structured questionnaire

Note: The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Each evaluation item was prefaced with the phrase "This teaching model…". Data on participants' age and gender were also collected.

Tools/Instruments

The study used an online questionnaire (Table 1), adjusted from a study by Li Cai et al. [12] to check students' views of the learning intervention. The instrument had 12 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). In the original study, the questionnaire showed good reliability, with a reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.85, showing high internal consistency.

Content validity had been previously set up through expert review to ensure the items were related to the educational context.

In the present study, the questionnaire was adjusted to include demographic information such as age and gender, in addition to the 12 evaluation items (Table 1). The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. To ensure content validity in the current context, the adjusted instrument was reviewed by three experts in the field. The Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) values ranged from 0.67 to 1.00. Specifically, Items 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, and 11 received an IOC score of 0.67, while Items 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, and 12 received an IOC score of 1.00. These results show that the items were generally appropriate and matched the research goals.

Revisions were made based on expert feedback to improve item clarity and contextual relevance. Before the main data collection, a pilot test was done with 10 students who shared similar characteristics with the target population to check the reliability of the adjusted instrument. The internal consistency of the questionnaire, determined using Cronbach's alpha, which was 0.95, showing a high level of reliability.

Data collection methods

The study design included classroom activities within a flipped classroom and case-based learning model for fourth-year medical students. This included research-curated teaching videos, along with dedicated case study videos that encouraged discussions on patient diagnoses, investigations, pathophysiology, treatment, and potential complications. Initially, the course plan was developed based on the approved medical curriculum from the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME). Then, topics within the course content were selected based on the reference text and added to with current research articles. Content delivery included in-classroom PowerPoint presentations and video recordings of prior lectures by the instructor. These videos were initially uploaded to the University website via the Medical Knowledge Center of MedNU and then made available for download for the current classes. Additionally, the instructor prepared recordings of various case studies, ensuring informed consent was gotten from all patients and parents involved. The case studies featured in the videos included patient visits to the outpatient pediatric clinic and inpatient admissions to the pediatric ward. The video content provided a complete demonstration of clinical history taking, systematic and thorough physical examination across all major body systems, and the collection of related clinical data. This included detailed assessments of general appearance, as well as focused examinations of the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat, in addition to the cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal, neurological, and musculoskeletal systems. Two weeks before the start of classroom activity, students were introduced to the course as well as the teaching and learning approach. Home learning activities, including videos (e-learning) of previous lectures by the instructor available on the University website, were also assigned and explained. At the beginning of the classroom activity, a pre-test was given to all students, with a maximum score of 10 points.

The pre-test consisted of 10 questions designed to check the students' prior knowledge, and scoring guidelines were explained in advance. Students who scored 5 or below were identified as potentially needing additional support to improve their understanding and engagement with the video content. Rather than being excluded, these students were encouraged to review the materials more thoroughly and were provided extra resources and guidance as needed. No student was excluded based on pre-test performance.

Following the pre-test, the instructor carried out classroom activities guided by the PERMA mode (Table 2). Although the PERMA well-being model served as the conceptual framework for instructional design, this study focused on checking students' satisfaction and views of their learning experience rather than measuring well-being outcomes directly. The facilitator was briefed and trained in advance on how to apply the PERMA framework to session design. This included summarizing the video content and presenting case-base videos materials to encourage in-depth classroom discussions. During the six-hour classroom session, students and the instructor worked together to analyze each case, clarified misconceptions, and looked into related topics. The instructor mainly acted as a facilitator, encouraging active taking part and inquiry. Discussions went beyond the case materials to include additional topics raised by students, such as lung sound auscultation and identification. The session ended with a PowerPoint presentation reinforcing key concepts and providing extra foundational knowledge and clinical diagnostic considerations. At the end of the 6-hours classroom session, the 22 students took a post-test quiz consisting of the 10 questions. This post-test was given to check short-term knowledge retention.

The students then completed an online questionnaire via Google Forms right away after the session (T1), and again one month later (T2) to check long-term satisfaction with the teaching model and knowledge retention, enabling comparison with their initial answers (Figure 1).

Table 2. Educational activities and their intended objectives

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Means and Standard Deviations (SD) were calculated for continuous variables, while and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables such as age and gender.

The normality of continuous variables, including aggregated Likert-scale scores, was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of Q–Q plots. The results showed no big deviation from a normal distribution; therefore, parametric tests were deemed appropriate for later analyses.

Paired samples t-tests were done to compare pre- and post-intervention scores on self-perceived competence and satisfaction.

Although Likert-scale data are ordinal in nature, the aggregated scores came close to continuous, normally distributed variables, supporting the use of parametric methods.

Future studies may consider complementary non-parametric analyses to confirm these findings. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Of the 22 students taking part, 7 were male (31.8%). The mean age was 23 years. The result showed a mean pre-test score of 8.18 ± 1.59 points and a post-test score of 8.77 ± 1.11 points, showing no big difference (p = 0.114).

The Google Forms questionnaire, checking students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction with the learning model, was completed by all students, with a response rate of 100%. With a maximum response score of 5, students expressed agreement with the teaching model. The researcher observed that most students were actively engaged in classroom activities and discussions related to the case studies and there were no signs of disengagement or boredom among them. Students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction were checked at two time points: right away after the classroom session (T1) and one month later (T2). No statistically big difference was observed in learning motivation between T1 and T2 (T1: 4.23 ± 0.81; T2: 4.55 ± 0.67; p = 0.184). Descriptive comparisons suggested slight improvements over time in self-directed learning (T1: 4.41 ± 0.73; T2: 4.45 ± 0.74; p = 0.840), memory retention (T1: 4.23 ± 0.81; T2: 4.41 ± 0.73; p = 0.446), and critical thinking skills (T1: 4.09 ± 0.92; T2: 4.41 ± 0.80; p = 0.201), although these differences were not statistically big.

Similarly, while not statistically big, students at T2 reported marginally higher scores in perceived patient management abilities (T1: 4.23 ± 0.69; T2: 4.36 ± 0.79; p = 0.525) and teamwork skills (T1: 3.82 ± 0.91; T2: 4.09 ± 0.92; p = 0.300).

They showed slightly greater confidence in applying knowledge to patient care (T1: 4.41 ± 0.73; T2: 4.91 ± 0.59; p = 1.000) and modest improvement in lung sound assessment skills (T1: 4.32 ± 0.65; T2: 4.50 ± 0.80; p = 0.383), a core competency in pulmonary diagnosis.

Overall satisfaction with the learning model stayed consistently high across both time points, (T1: 3.77 ± 1.15; T2: 3.86 ± 1.24; p = 0.790).

Self-reported understanding of the content was identical between the two groups (T1: 4.41 ± 0.67; T2: 4.55 ± 0.74; p = 0.561), and stress levels related to classroom activities were comparable (T1: 3.55 ± 1.41; T2: 3.64 ± 1.26; p = 0.851). Interestingly, students at T2 reported greater diligence in watching the instructional videos than those at T1, although this difference was not statistically big (T1: 4.05 ± 0.79; T2: 4.36 ± 0.85; p = 0.167) (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of students' self-perceived competence and satisfaction scores between two time points

Note: Data presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation. T1: First survey time point, T2: Second survey time point.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; Sig. statistical significance; p, probability value.

Discussion

Overall, students reported high levels of satisfaction with the teaching model, with the highest-rated aspect being the perceived benefit to their learning and knowledge understanding. In contrast, the lowest ratings were related to stress levels, suggesting that the model did not cause big stress. These findings show that the combination of the FC and Case-Based Learning (CBL) approaches within the PERMA model of well-being contributed to a positive, low-stress learning experience, that improved understanding and engagement.

All questionnaire items received mean scores of four or higher, reflecting strong student approval of the teaching approach. The highest-rated items highlighted perceived improvements in knowledge understanding, self-directed learning, and the application of knowledge in clinical contexts. These findings match previous studies showing that FC and other active learning strategies help deeper learning, motivation, and clinical reasoning skills in medical education [12, 15].

One reason for these results could be that the FC approach frees up cognitive resources for higher-order thinking during in-class activities by letting students study foundational material on their own before class. The focus on self-directed learning aligns with critical skills in clinical practice, where students must solve problems independently and make well-informed decisions. This approach might better prepare students for patient care duties by fostering these abilities in a controlled, cooperative setting.

Despite the requirement that students watch lectures on tape before participating in class activities, some students expressed less interest in the pre-course materials. Clinical workload, time constraints, and limited access to dependable technology were the main obstacles found. The effectiveness of flipped learning models may be hampered by these difficulties, which are a reflection of larger structural problems, especially in medical education settings where students must juggle clinical and academic obligations.

Prior research on the shortcomings of the flipped classroom approach has identified similar problems [24, 32–34]. For example, since discussions and case analyses depend on prior knowledge, the benefits of in-class learning are diminished when students are unable to sufficiently prepare before class. Under such circumstances, the flipped model's active learning element might lose its significance or even work against you. Therefore, these findings emphasize the need for better institutional mechanisms, such as protected learning time, improved technological infrastructure, and strategies to encourage equitable access to pre-class materials.

It is possible that some students prioritized meeting the minimum preparation requirement rather than fully engaging with the video, reflecting a surface-level or strategic learning approach driven by time constraints. Previous study reporting higher engagement levels often involved student cohorts with fewer competing obligations or better institutional support [35]. This suggests that while preparatory assessments may encourage compliance, they do not necessarily guarantee meaningful engagement. In order to support deeper learning, future research could examine complementary techniques like reflective prompts or in-class application tasks.

There were no statistically significant differences in mean scores between the Google Forms questionnaire responses at T1 (shortly after the intervention) and T2 (one month later). According to this research, the teaching approach resulted in long-term satisfaction and perceived learning advantages in addition to instant favorable opinions. The consistency of scores across time points shows that students continued to value the learning experience even after the initial exposure, reflecting the lasting impact of the instructional design.

These results match prior studies showing that active learning strategies, such as case-based and problem-based learning, improve both satisfaction and academic performance [12, 14, 15, 36]. However, in contrast to the majority of earlier research, this study reexamined student opinions one month later, enabling evaluation of long-term impacts. The PERMA well-being framework may have contributed to longer-term satisfaction by fostering emotional engagement and a sense of purpose, as indicated by the consistently high ratings.

The difference did not reach statistical significance, even though post-test scores were marginally higher than pre-test scores. This might be because there were only ten test items, which decreased the assessment's sensitivity to pick up on minute learning gains. The short interval between pre- and post-tests may also have limited the opportunity for deeper cognitive combination of the material. Additionally, the test items may have emphasized surface-level recall rather than higher-order thinking, which may not fully capture the outcomes associated with FC and CBL approaches. Future studies should consider developing more complete and confirmed assessments—ideally including application-based or problem-solving items—to better check learning outcomes in active learning environments.

The teaching model was designed based on the PERMA framework to help student well-being during classroom activities. Specifically, it aimed to grow positive emotions by creating enjoyable learning experiences and encouraging open communication, thereby improving engagement. Case-based discussions helped meaningful relationships among peers, while supportive instructor interactions contributed to positive emotional experiences. Students were able to connect theoretical ideas to real-world application through the use of authentic clinical scenarios, which gave the content purpose and significance. By aligning activities with individual learning objectives and promoting reflection on skill development and mastery, the model also promoted achievement.

However, empirical data directly measuring changes in students' well-being across the PERMA dimensions were not collected for this study. Therefore, even though the PERMA framework served as the foundation for the instructional design, its effect on wellbeing remains theoretical in this study. To offer empirical proof of the model's impact on students' well-being, future research should incorporate validated metrics of PERMA-related outcomes.

It is important to recognize the various limitations of this study. First, the sample size was small, which could limit the findings' generalizability and statistical power. Second, the study was conducted in a single location, which limited the results' generalizability to other organizations or situations.

Third, it is more difficult to make causal conclusions regarding the efficacy of the teaching model when there is no control group. Furthermore, it's possible that the limited number of questions in the pre- and post-tests made it more difficult to identify significant gains in knowledge. To increase the validity of the results, future research should think about utilizing a wider range of assessment tools. Last but not least, implementing this teaching model required extensive instructor preparation, especially for creating and integrating case-based video resources. Even though students were very satisfied, the demands of the instruction might make wider adoption difficult. Implementation this teaching model could be gradually integrated into existing medical curricula as a supplemental or elective learning module. Educators can apply the PERMA framework to design learning environments that enhance student well-being alongside academic performance, particularly in areas such as self-directed learning, teamwork, and reflective practice. Future large-scale studies should explore how this approach can be optimized across different disciplines, cohorts, and cultural contexts, as well as assess its long-term effects on knowledge retention, clinical reasoning, and professional development.

Establishing institutional support and faculty development programs will be critical for sustainable implementation and broader adoption.

Conclusion

This pilot study examined the implementation of a flipped classroom and case-based learning model informed by the PERMA framework among small groups of fourth-year medical students.

Although no statistically big differences were observed between pre- and post-test scores, students reported high levels of satisfaction and engagement.

These findings show that combining the PERMA framework with active learning strategies may provide a supportive and effective educational environment. Further studies with larger samples and more rigorous designs are warranted to confirm these results and look into the model's broader impact on learning outcomes and student well-being.

Ethical considerations

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the University. Additionally, verbal informed consent was gotten from the students taking part.

The study followed established ethical principles and institutional guidelines throughout. The code for the approved work was COE No. 249/2023 IRB No. P3-0104/2566.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

To enhance linguistic clarity and stylistic consistency, artificial intelligence (AI)-based grammar and language refinement tools were utilized during manuscript preparation.

This process aimed to produce a polished academic text that meets the linguistic standards expected in high-impact international journals.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Miss Daisy Gonzales from the International Relations Section, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University for her valuable help in editing the manuscript.

A special acknowledgment also to Mr. Roy I. Morien of the Naresuan University Graduate School for his editing of the grammar, syntax and general English expression in this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Assoc.Prof. Klaita Srisingh reviewed the literature, designed the study, developed the methodological frame work for the study, performed data collection and data analysis, wrote the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

Ms. Kornthip Jeephet developed the methodological frame work for the study, performed data collection and data analysis, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding received for the study.

Data availability statement

The data that support of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research students but are available from the corresponding author (K.S.) upon reasonable request.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2025/08/4 | Accepted: 2025/11/16 | Published: 2025/11/19

Received: 2025/08/4 | Accepted: 2025/11/16 | Published: 2025/11/19

References

1. Zayapragassaravan Z, Menon V, Kar S, Batmanabane G. Understanding critical thinking to create better doctors. J Adv Med Educ Res. 2016;1(3):9-13.

2. West M. How can good performance among doctors be maintained? BMJ. 2002;325(7366):669-70. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.325.7366.669] [PMID] []

3. Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):433-50. [DOI:10.1037/amp0000298] [PMID] []

4. McGee RG, Wark S, Mwangi F, Drovandi A, Alele F, Malau-Aduli BS, et al. Digital learning of clinical skills and its impact on medical students' academic performance: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:1477. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-024-06471-2] [PMID] []

5. Tudor Car L, Soong A, Kyaw BM, Chua KL, Low-Beer N, Majeed A. Health professions digital education on clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review by Digital Health Education collaboration. BMC Med. 2019;17:139. [DOI:10.1186/s12916-019-1370-1] [PMID] []

6. Altintas L, Sahiner M. Transforming medical education: the impact of innovations in technology and medical devices. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2024;21(9):797-809. [DOI:10.1080/17434440.2024.2400153] [PMID]

7. Seligman MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Atria Books; 2011.

8. Iammeechai W. Applying positive psychology in medical curriculum: creating engaging and meaningful interactive lecture. Siriraj Med Bull. 2024;17(2):181-7. [DOI:10.33192/smb.v17i2.265290]

9. Lou J, Xu Q. The development of positive education combined with online learning: based on theories and practices. Front Psychol. 2022;13:952784. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952784] [PMID] []

10. Afshar M, Zarei A, Moghaddam MR, Shoorei H. Flipped and peer-assisted teaching: a new model in virtual anatomy education. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:722. Algarni A. Biomedical students' self-efficacy and academic performance by gender in a flipped learning haematology course. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):443. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-024-05421-2] [PMID] []

11. Cai L, Li YL, Hu XY, Li R. Implementation of flipped classroom combined with case-based learning: a promising and effective teaching modality in undergraduate pathology education. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(5):e28782. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000028782] [PMID] []

12. Honarpishe R, Ghotbi N, Jalaei S. Design, implementation, and evaluation of flipped classroom for postgraduate physiotherapy students. J Mod Rehabil. 2024;18(1):62-9. [DOI:10.18502/jmr.v18i1.14730]

13. Hu X, Zhang H, Song Y, Wu C, Yang Q, Shi Z, et al. Implementation of flipped classroom combined with problem-based learning: an approach to promote learning about hyperthyroidism in the endocrinology internship. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):290. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-019-1714-8] [PMID] []

14. Yang F, Lin W, Wang Y. Flipped classroom combined with case-based learning is an effective teaching modality in nephrology clerkship. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):276. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-021-02723-7] [PMID] []

15. Bösner S, Pickert J, Stibane T. Teaching differential diagnosis in primary care using an inverted classroom approach: student satisfaction and gain in skills and knowledge. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:63. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-015-0346-x] [PMID] []

16. Bergmann J, Sams A. Flip your classroom: reach every student in every class every day. Washington DC: International Society for Technology in Education; 2012.

17. Galway LP, Corbett KK, Takaro TK, Tairyan K, Frank E. A novel integration of online and flipped classroom instructional models in public health higher education. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:181. [DOI:10.1186/1472-6920-14-181] [PMID] []

18. Ryan MD, Reid SA. Impact of the flipped classroom on student performance and retention: a parallel controlled study in general chemistry. J Chem Educ. 2016;93(1):13-23. [DOI:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00717]

19. van Vliet EA, Winnips JC, Brouwer N. Flipped-class pedagogy enhances student metacognition and collaborative-learning strategies in higher education but effect does not persist. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14(3):ar26. [DOI:10.1187/cbe.14-09-0141] [PMID] []

20. Al-Zahrani AM. From passive to active: the impact of the flipped classroom through social learning platforms on higher education students' creative thinking. Br J Educ Technol. 2015;46(6):1133-48. [DOI:10.1111/bjet.12353]

21. Bhagat KK, Chang CN, Chang CY. The impact of the flipped classroom on mathematics concept learning in high school. J Educ Technol Soc. 2016;19(3):134-42. Available from:

22. Chen L, Chen TL, Chen NS. Students' perspectives of using cooperative learning in a flipped statistics classroom. Australas J Educ Technol. 2015;31(6):621-40. [DOI:10.14742/ajet.1876]

23. Fautch JM. The flipped classroom for teaching organic chemistry in small classes: is it effective? Chem Educ Res Pract. 2015;16(1):179-86. [DOI:10.1039/C4RP00230J]

24. Smitha JD. Student attitudes toward flipping the general chemistry classroom. Chem Educ Res Pract. 2013;14(4):607-14. [DOI:10.1039/C3RP00083D]

25. Khanova J, Roth MT, Rodgers JE, McLaughlin JE. Student experiences across multiple flipped courses in a single curriculum. Med Educ. 2015;49(10):1038-48. [DOI:10.1111/medu.12807] [PMID]

26. Kiviniemi MT. Effects of a blended learning approach on student outcomes in a graduate-level public health course. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:47. [DOI:10.1186/1472-6920-14-47] [PMID] []

27. Kong SC. Developing information literacy and critical thinking skills through domain knowledge learning in digital classrooms: an experience of practicing flipped classroom strategy. Comput Educ. 2014;78:160-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.05.009]

28. Porcaro PA, Jackson DE, McLaughlin PM, O'Malley CJ. Curriculum design of a flipped classroom to enhance haematology learning. J Sci Educ Technol. 2016;25(3):433-40. [DOI:10.1007/s10956-015-9599-8]

29. Thalerngnawachart C, O'Donnell JM, Surabenjawong U. Comparison between the standard teaching and the Thai version of blended teaching on basic airway management in Siriraj medical students. Siriraj Med J. 2024;76(7):422-8. [DOI:10.33192/smj.v76i7.266174]

30. Wongwandee M, Paritakul P. Pre-class versus in-class video lectures for the flipped classroom in medical education: a non-randomized controlled trial. Siriraj Med J. 2020;72(6):476-82. Akçayır G, Akçayır M. The flipped classroom: a review of its advantages and challenges. Comput Educ. 2018;126:334-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021]

31. Rajasekaran R, Padmanath K, Sasikumar S, Richard Jagatheesan PN. Transformation of veterinary education through the flipped classroom model: advantages, challenges, and future implications. Indian J Vet Sci Biotechnol. 2024;20(2):1-6.

32. Zainuddin Z, Halili SH. Flipped classroom research and trends from different fields of study. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2016;17(3):313-40. [DOI:10.19173/irrodl.v17i3.2274]

33. Tune JD, Sturek M, Basile DP. Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013;37(4):316-20. [DOI:10.1152/advan.00091.2013] [PMID]

34. Shen J, Qi H, Mei R, Sun C. A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:135. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-024-05080-3] [PMID] []

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |