Thu, Jan 29, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 4 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(4): 18-29 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1403.134

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rad M, Feizabadi M, Assarzadeh H, Chaman R, Yazdimoghaddam H, Javadinia S A. Barriers to implementing findings from theses and dissertations: a qualitative study. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (4) :18-29

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2474-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2474-en.html

Mostafa Rad1  , Mansoureh Feizabadi2

, Mansoureh Feizabadi2  , Hossein Assarzadeh3

, Hossein Assarzadeh3  , Reza Chaman4

, Reza Chaman4  , Hamideh Yazdimoghaddam4

, Hamideh Yazdimoghaddam4  , Seyed Alireza Javadinia *5

, Seyed Alireza Javadinia *5

, Mansoureh Feizabadi2

, Mansoureh Feizabadi2  , Hossein Assarzadeh3

, Hossein Assarzadeh3  , Reza Chaman4

, Reza Chaman4  , Hamideh Yazdimoghaddam4

, Hamideh Yazdimoghaddam4  , Seyed Alireza Javadinia *5

, Seyed Alireza Javadinia *5

1- Iranian Research Center of Healthy Aging, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

2- Department of Scientometrics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

3- School of Medicine, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

4- Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

5- Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran ,Javadinia.alireza@gmail.com

2- Department of Scientometrics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

3- School of Medicine, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

4- Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

5- Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 496 kb]

(177 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (403 Views)

Full-Text: (3 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Graduate and postgraduate theses in medical sciences aim to identify clinical problems, propose therapeutic strategies, and inform health policies. However, their findings are often not applied in practice. This study explored barriers to implementing results from postgraduate theses.

Materials & Methods: This qualitative study employed a conventional content analysis approach and was conducted from January 31 to March 31, 2025. Ten faculty members participated, selected through purposive sampling until data saturation was achieved. Data were collected via semi-structured, individual interviews and analyzed using Elo and Kyngäs’s method. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, Lincoln and Guba’s criteria—credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability—were applied.

Results: Qualitative data analysis yielded 500 initial codes, which were organized into 63 subcategories, 12 primary categories, and ultimately synthesized into 4 main categories. The four categories included: “barriers related to researchers and research itself”, “barriers related to organizational and managerial environments”, “barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff”, and “barriers related to policy and regulations”. The overarching, abstracted theme was identified as “systematic barriers to the application of research findings in the health system”.

Conclusion: This study identified four main categories of barriers that hinder the use of research evidence in healthcare: researcher- and research-related, organizational, professional, and policy barriers. Overcoming these challenges requires coordinated, multi-level strategies engaging researchers, healthcare providers, managers, and policymakers. Systematic action in these areas can promote evidence-informed decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

As a scientific and applied field, medical sciences play a significant role in improving public health and advancing healthcare systems [1]. Graduate and post-graduate theses in biomedical fields represent essential academic requirements that often generate valuable knowledge and enhance medical service quality [2]. However, many completed research projects remain shelved in libraries or buried in databases, with estimates indicating that 60-80% of student theses never reach practical application [3]. This situation not only wastes financial resources, time, and energy but also results in missed opportunities to improve public health [4].

The process of evidence-based policymaking relies on systematically identifying, evaluating, and applying the best available evidence for decision-making [5]. In this context, student theses constitute a significant knowledge source that could advance the field. The standard workflow for updating medical care involves reviewing literature and evaluating previous research before determining intervention methods [6], which necessitates evidence-based healthcare practices to achieve favorable patient outcomes [7].

The rising healthcare costs underscore the necessity for research-based practice in biomedical sciences, requiring cost-reduction measures across healthcare institutions. Contemporary medical students must demonstrate the benefits of their work to various stakeholders, including society, professions, service recipients, and governmental agencies. These imperative demands greater awareness of the obstacles preventing the application of research in practice. [8].

Addressing current challenges and anticipating future issues through scientific inquiry represents a crucial development pathway [9].

A significant concern in health services remains the gap between known effective treatments and routine care practices. Bridging this gap requires coordinated efforts to implement scientific findings and train skilled researchers [10], while ensuring research validity and reliability through comprehensive and reproducible results [11,12].

Clinical research remains fundamental to medical science advancement, with graduate students bearing substantial research responsibility in medical universities [13]. Consequently, their findings' quality directly influences practical application. The healthcare industry's ongoing digital transformation, characterized by cloud-based data storage and machine learning, is transforming healthcare data into valuable assets [14]. This evolution necessitates student engagement with emerging technologies to expand scientific knowledge. Well-conducted student research can generate high-quality, evidence-based knowledge that benefits decision-makers and reduces resource waste [15].

Previous research has identified various implementation barriers.

Latifi et al. highlighted knowledge stagnation, poor resource utilization, unpublished results, and low research quality in nursing [16].

Azizian et al. found that dental students faced research skill deficiencies, methodological knowledge gaps, statistical unfamiliarity, and limited information access. Insufficient research skills and inadequate resource access were identified as the primary individual and organizational barriers, respectively [17]. Research-active students predominantly reported organizational barriers, while non-research students cited personal obstacles [18].

Generally, graduate research in medical sciences aims to identify clinical problems, develop innovative therapies, and improve health policies [8].

Organizational support deficiencies and decision-making authority limitations have been identified as research utilization barriers [10]. The persistent underutilization of research results represents both missed opportunities and weaknesses in medical research management systems [18].

Previous studies have primarily investigated research barriers from faculty and researchers' perspectives, with limited attention to research utilization obstacles. This study addresses this gap by focusing on knowledge production-application disconnects.

Therefore, identifying existing barriers to implementing graduate research findings and developing effective strategies to overcome them becomes imperative. Employing qualitative methods, this investigation explores faculty members' experiences and perspectives to extract key themes and understand contextual nuances. The study aims to generate new knowledge and offer practical clinical guidance by identifying barriers to the application of graduate and postgraduate thesis findings.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This qualitative study employed a conventional content analysis approach, as outlined by Elo and Kyngäs from January, 31, 2025 to March, 31, 2025, and was conducted at the faculty members of the faculties of Nursing and Midwifery, Allied Health Sciences, and the Public Health Department at Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran Participants and sampling Participants were recruited through purposive sampling with maximum variation to ensure representation of a wide range of experiences and characteristics relevant to the research question.

The inclusion criteria were having already supervised at least one master’s thesis; having had its findings published in at least one scholarly article; and willingness to participate and share personal experiences.

The sole exclusion criterion was withdrawal of consent at any stage of the research.

In keeping with qualitative principles, the number of participants was not fixed in advance but was determined by the richness and depth of the data obtained; recruitment continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, defined as the point at which no new codes were identified and subsequent interviews merely confirmed previously collected data. For planning purposes, an initial range of 40–90 individuals per group had been anticipated.

Tools/Instruments

Semi-structured in-depth interview was used for data collection. Maximum variation sampling (considering age, gender, work experience, professional experience, educational level, managerial experience, and the number of these supervised) was employed to select the participants.

Data collection methods

Data were collected through semi structured, in depth interviews, a method valued in qualitative research for its flexibility and ability to elicit rich descriptions of lived experience. An interview guide, adapted to each participant group, ensured consistent coverage of key issues.

Data saturation was achieved after eight interviews. No new codes or subcategories emerged in the final two interviews, indicating that data saturation had been reached. The time and location of the interviews were agreed upon between the participants and the interviewer.

The researcher introduced herself at the start of each session, explained the study objectives, obtained written informed consent for participation and audio recording, reassured participants regarding confidentiality, and established rapport before initiating formal questioning. Interviews were conducted in a private setting, audio recorded with permission, transcribed verbatim immediately after completion, and supplemented with field notes. With participants’ consent, the interview commenced with warm-up questions, including the participant's self-introduction, age, work experience, professional academic experience, educational level, managerial experience, and the number of theses they had supervised. Following this, the main portion of the interview began with a general question regarding the obstacles to the application of research findings reported in master's theses. Gradually, more specific questions were asked, such as “What conditions can lead to these issues?”, “What strategies could improve the situation?”, and “What actions did you take as a supervisor?”."

If necessary, further probing questions were asked, such as "Could you explain more about this?", "What happened next?", "What occupied your thoughts?", "How did you feel?", etc.

Each interview session ended with the following two questions: "In your opinion, is there any other question I should have asked but failed to ask?" and "Do you have any questions for me?"

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis proceeded concurrently. Each transcript was read repeatedly to achieve immersion, condensed into initial codes, compared for similarities and differences, grouped into subcategories, merged into broader generic categories, and finally abstracted into a main overarching category. This process followed the stages of open coding, categorization, and abstraction described by Elo and Kyngäs [17]. After multiple rounds of listening, reading, and immersion in the data, an overall picture was obtained, meanings were extracted, key ideas were highlighted, and codes were assigned based on their relationships to one another.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured according to Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability, achieved through prolonged engagement with participants and data, iterative coding and review, member checking (returning transcripts and preliminary codes to participants for verification), peer debriefing with the research team, and maintaining a detailed audit trail documenting the study process from inception to completion. Additional measures included spending sufficient time on data collection and analysis to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants, reviewing the interviews and codes within the research team, building strong rapport with participants to facilitate deeper interviews, engaging in prolonged data processing, reading the interviews multiple times to refine codes, reviewing various stages of analysis in repeated team sessions, and having other colleagues review the codes.

Interviews, codes and extracted categories were given to some experts familiar with qualitative research methods; they were asked to review the coding and analysis methods and provide comments on its accuracy. In controversial cases, discussions were made and consensus was achieved. Different stages of analysis were recorded and described to be used for evaluation by external experts. Data were analyzed using MAXQDA 24 software.

Results

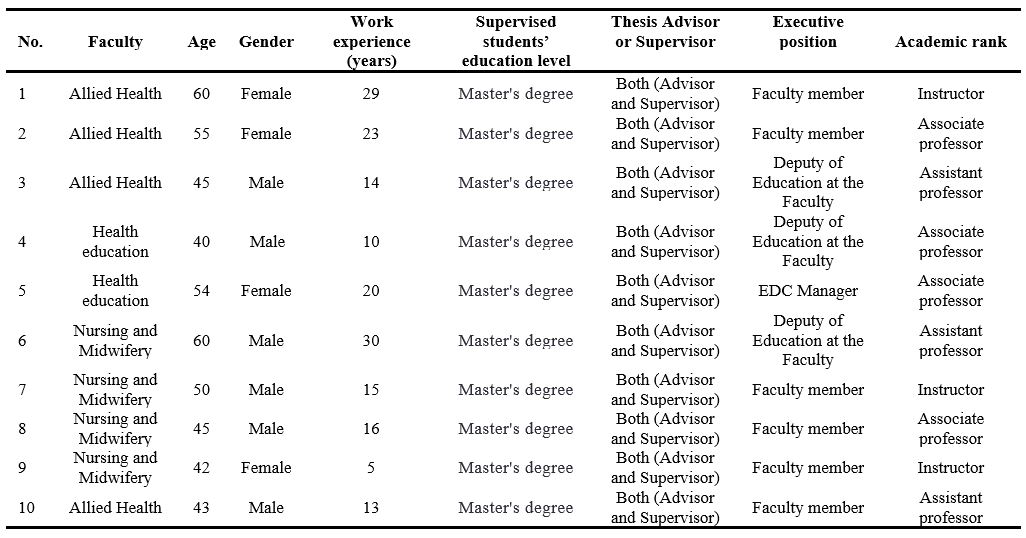

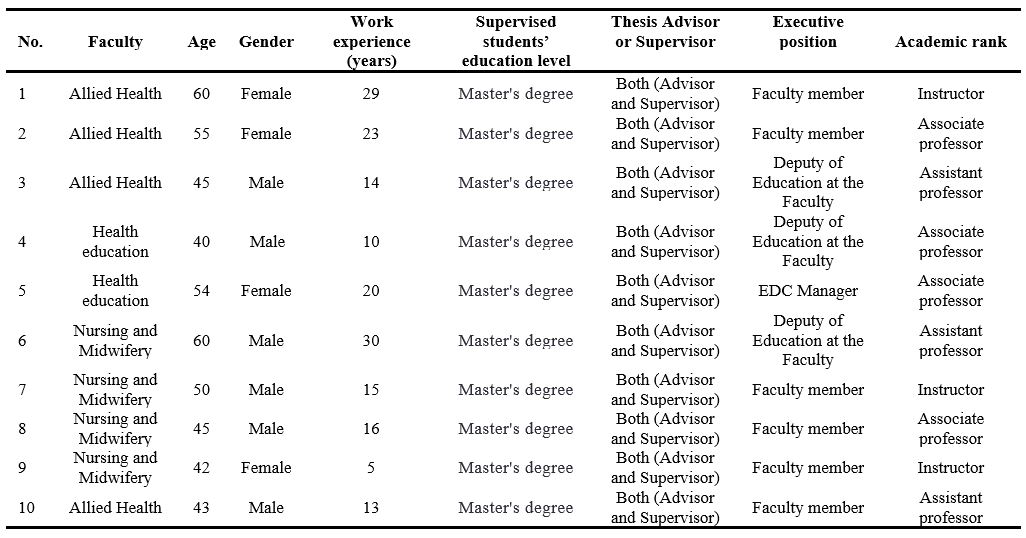

In this qualitative study, a total of 10 semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with faculty members. Participants included six men and four women aged 40 to 60 years, with work experience ranging from 5 to 30 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

Abbreviation: EDC, educational development center.

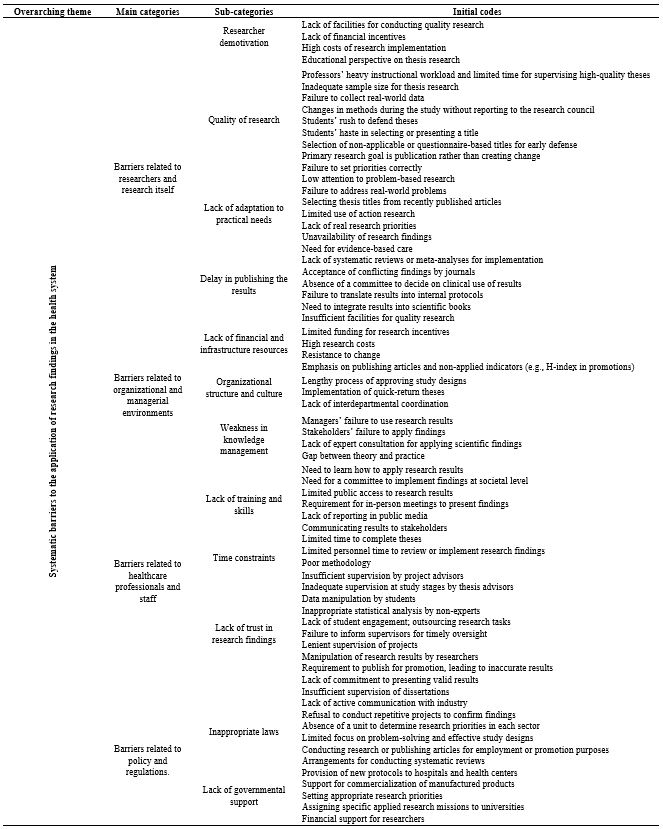

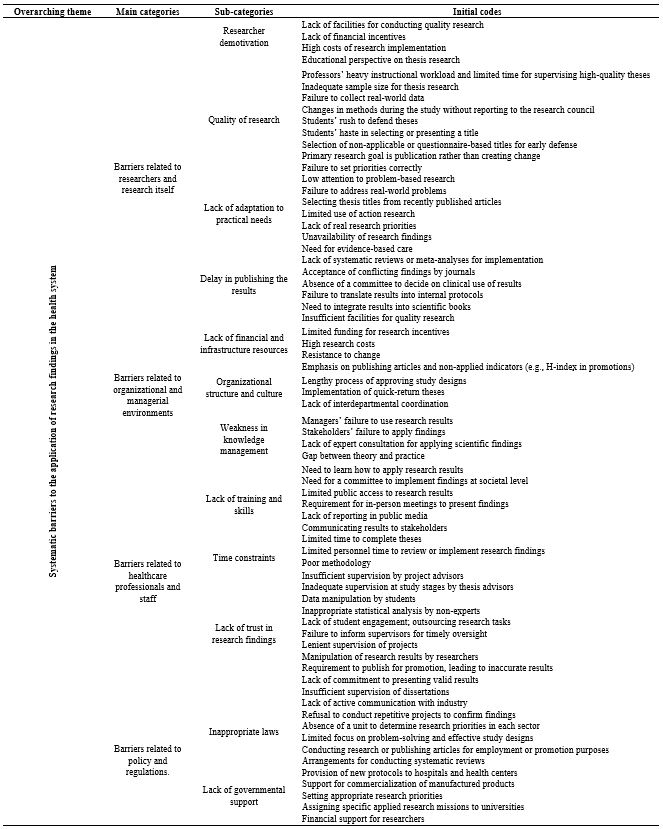

Qualitative data analysis yielded 500 initial codes, which were organized into 63 subcategories, 12 primary categories, and ultimately synthesized into 4 main categories. The four categories were: ‘barriers related to researchers and research itself,’ ‘barriers related to organizational and managerial environments,’ ‘barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff,’ and ‘barriers related to policy and regulations.’ The overarching, abstracted theme was identified as: “systematic barriers to the application of research findings in the health system” (Table 2).

Table 2. Themes, main categories, subcategories, and initial codes

Barriers related to researchers and research itself

This concept emerged from four primary subcategories: “researcher demotivation”, “quality of research”, “lack of adaptation to practical needs”, and “delay in publishing the results”. This concept reveals that the failure to implement research findings in the health system does not result from a single issue, but from a complex interplay of systemic barriers. These obstacles, categorized as research-related and researcher, managerial and organizational, healthcare professional-related, and legal challenges and policy, are deeply interconnected and often self-reinforcing.

Researcher demotivation: The experiences of participants revealed that the necessary facilities for conducting high-quality research were not provided for them.

Additionally, low research budgets and the high costs of implementing projects often led to a bias in student theses toward questionnaire-based, low-quality projects. The goal became merely publishing a paper rather than applying the findings in a real setting where problems awaited scientific solutions; note the statement below by one participant: "Research work needs money; if it is not provided, the student or his/her supervisor has to pay it out of pocket, and that means that useful work is not undertaken..." (Participant 6)

Quality of research: Some research studies never turn out to be applicable in practice due to their weaknesses of methodology, inappropriate sampling, or dissociation from clinical needs. Participants stated that some of the theses they completed were not of high quality. Contributing factors included supervisors’ busy instructional schedules and lack of time for student research, viewing theses merely as educational exercises, small sample sizes that hampered generalizability, theses not based on real problems or healthcare priorities, goals set for employment or promotion purposes, and students’ hasty selection of topics and completion of research. Even in priority-oriented topics provided by the Ministry of health, research questions were hastily formulated, which tended to reduce their quality; note the statement below by one of the supervisors:

“The thesis constitutes a foundational exercise in research methods. It is a supervised learning process in which the student acquires research competencies systematically. Given that students are novice researchers with minimal experience, their work cannot be expected to attain perfection..." (Participant 10)

Lack of adaptation to practical needs: Research is often conducted either in laboratory or under certain circumstances that are different from real healthcare settings; accordingly, most of the results obtained in student dissertations tend to become less applicable to real settings. Participants stated that there was little attention paid to research arising from real problems, and the actual problems in clinical practice and society were not addressed. Thesis topics are often rooted in the latest published articles, but action research is not utilized due to students' unfamiliarity with this type of research. Consequently, thesis research does not precisely correspond to the practical needs of society and clinical practice, hindering the use of obtained results in practice; note the statement below by one of the professors:

"The theses we supervise are not based on the actual problems of the wards; the students come to us with a research title borrowed from a newly published article, and we approve it..." (Participant 7)

Delay in publishing the results: Participants stated that sometimes research is published long after it is completed, and by that time, the obtained results lose their relevance and novelty. For them, that was because journals tended to accept contradictory results while they are less interested in insignificant findings. Other reasons included the student researchers’ reluctance to publish articles extracted from their theses and supervisors’ lack of time to assist students in publication. However, care provision should be evidence-based and rooted in scientific findings. This requires systematic reviews and the inclusion of research findings in reference books or ministry declarations, which altogether delays public accessibility to those findings: note the statement below by one of the supervisors.

“The student works on the thesis and then abandons it...; the professor, who also doesn't have time to publish, might get around to publishing it a few years later...” (Participant 1)

Barriers related to organizational and managerial environments

This concept emerged from three primary subcategories: “lack of financial and infrastructural resources”, “organizational structure and culture”, and “weaknesses in knowledge management”. The obstacles within the ‘organizational and managerial environment’ represent some of the most fundamental challenges an organization can face. The three primary barriers—a lack of financial and infrastructural resources, an ineffective organizational structure and culture, and deficiencies in knowledge management—are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

This interplay traps the organization in a vicious cycle, severely impeding its capacity for innovation, adaptation, and long-term goal achievement. Consequently, overcoming these challenges requires a comprehensive, simultaneous approach addressing all three dimensions.

Lack of financial and infrastructural resources: Participants stated that the implementation of research findings required adequate financial resources, equipment, and infrastructure, which are often not available to junior researchers; note the statement below by one of the participants:

"For example, health education theses require the preparation of software or gamification designs, etc., which is very costly, and effective research cannot be conducted under these conditions..." (Participant 4)

Organizational structure and culture: Many healthcare centers and organizations have traditional structures with no flexibility to accommodate and implement changes. A culture of resistance to change can also prevent the implementation of new findings. Participants stated that in the organizational culture of medical sciences which are resistance to change, the emphasis on publishing articles and non-applied indicators such as the effect of H-index in a professor's promotion, the lengthened process of approving study designs, the implementation of quick-return theses, and the lenience of research councils towards students to conduct high-quality and applied studies are among the reasons for the low quality of theses and, ultimately, their non-applicability. For instance, note the statement below:

“Contemporary academic systems often prioritize quantitative research output, such as publication count and H-index, in hiring and promotion decisions. This can create an environment where the perceived impact of these metrics outweighs considerations of a study's intrinsic scholarly or practical utility..." (Participant 8)

Weaknesses in knowledge management: Participants stated that the organization does not have an effective knowledge management system to identify, organize, and implement scientific knowledge in practice. Participants noted several factors contributing to weak knowledge management, which hinder the application of research results. These included a lack of interdepartmental coordination to present research findings for practical use, managers’ failure to apply results, stakeholders’ lack of engagement with findings, and insufficient consultation with experts on how to use scientific evidence. Consider the statement below by one of the supervisors:

"The current knowledge translation that exists is not accessible to everyone; many people do not even know what it is or where it is. Even the researchers themselves do not have access to the knowledge translation of other universities. Widespread unfamiliarity with KT resources, coupled with institutional barriers that restrict access even for researchers, severely limits the dissemination and utility of scientific evidence..." (Participant 9)

Barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff

This concept emerged from three primary subcategories: “lack of training and skills”, “time constraints”, “lack of trust in research findings”. The barriers at the level of healthcare professionals represent a pivotal challenge in the process of healthcare system transformation. These three core obstacles—deficiencies in training and skills, limited time, and distrust of research evidence—interact in a vicious cycle: insufficient skills foster skepticism toward new evidence, while time constraints exacerbate these issues by preventing meaningful engagement with new knowledge or skill development. Collectively, they pose a major impediment to implementing evidence-based care, compromising service quality. Addressing these interrelated barriers therefore requires a coordinated strategy that targets all three dimensions simultaneously.

Lack of training and skills: Some healthcare staff are not familiar with the necessary knowledge and skills to implement new findings. Participants stated that utilizing thesis findings required certain training and skills because the reported findings were only in the form of numbers, figures, and statistics. The gap between theory and practice lies in how to apply these results, which entails an expert committee to operationalize the findings in society and make the research results publicly available. It further demands holding in-person meetings with researchers to present the findings or report the results from an operational perspective in the form of knowledge translation. Currently, knowledge translation is not available in public media, and stakeholders are even unaware of it; therefore, they require the necessary training in this regard; look at the following statement:

" The technical language of medical research can pose a barrier to clinicians seeking to apply new findings. When confronted with such specialized literature, clinicians often rely on intermediaries to translate the results or provide a concise summary of the core evidence." (Participant 2)

Time constraints: Workers of the healthcare and therapeutic sections often encounter a heavy workload and cannot allocate enough time to study and apply new findings in practice. Participants stated that students have limited time to complete their theses, which can affect the quality of their research. Similarly, healthcare personnel have limited time to use the results of all research findings and study their details due to their heavy workload in hospital wards.

"Sometimes these student researchers are in such a hurry to defend their theses and graduate that they resort to doing anything." (Participant 6)

Lack of trust in research findings: The study participants further stated that one of the significant reasons preventing the use of thesis results is mistrusting the validity or applicability of those results. Poor design and methodology, insufficient supervision by study supervisors and advisors, possibility of data manipulation by some student researchers, inappropriate statistical analysis particularly by non-experts, lack of student engagement in their own research work, outsourcing the work, failure to inform supervisors in a timely manner for supervision, lack of strict supervisors,

alteration of the results, requirements for publication of articles for promotion purposes and publication with imprecise results, and lack of commitment to presenting proper results can account for the mistrust associated with student thesis reports. The statement below can be of interest:

"When neither the thesis advisor nor the project supervisor oversees the research, what do you think will come out of it? Potential consequences include methodological errors, an unfocused research question, and ethical oversights. Without expert guidance, the project is unlikely to achieve its potential contribution to the field and may not fulfill the criteria for a credible academic exercise. Consequently, the project often fails to make a meaningful contribution to the field or meet the standards of a credible academic exercise..." (Participant 4)

Barriers related to policy and regulations

This concept emerged from two primary subcategories: “inappropriate laws” and “lack of governmental support”. Obstacles stemming from 'Policies and Regulations' constitute a critical, overarching framework that shapes other organizational and individual barriers. The two primary subcategories in this domain—inadequate regulations and insufficient institutional support—share a reciprocal and reinforcing relationship. Restrictive regulations constrain the ability of institutions to provide effective support, while a lack of financial and executive backing renders enacted legislation ineffective.

This negative synergy creates an implementation gap that fundamentally impedes the achievement of reform objectives at the ground level. Consequently, breaking this cycle requires the concurrent revision of outdated policies and the provision of concrete, targeted institutional support.

Inappropriate laws: Participants stated that some rules and regulations may prevent the implementation of student research findings.

They highlighted several regulations set by the research council, including the rejection of repetitive study designs—even when such designs are necessary to confirm previous findings, the absence of active collaboration with industry, the lack of a committee to establish genuine research priorities within healthcare sectors, and insufficient discipline and oversight for rigorous thesis monitoring. Collectively, these issues have weakened results and pushed them further from practical application. Note the statement below:

"Well, for study findings to be applicable in clinical practice, it needs to be researched several times in several settings, but the council for postgraduate studies often emphasizes that the research must be innovative..." (Participant 1)

Lack of governmental support: Lack of financial and policy support from the government can hinder the implementation of applied projects. Participants stated that the government can assist by providing arrangements for conducting systematic reviews, providing new protocols to hospitals and health centers, helping in the commercialization of manufactured products, determining the right priorities for conducting applied research, assigning the mission to conduct research in each applied field to a university, and most importantly, providing financial support to researchers in conducting applied research. Consider the following statement:

"For the past few years, incentive policies have decreased, and the funds approved for projects are not at all sufficient, and impactful work can no longer be done. The pathway to clinically applicable research requires validation through repeated studies in diverse settings. Researchers must therefore navigate the challenge of designing studies that are both original and capable of contributing to a robust evidence base…" (Participant 8)

Discussion

Graduate student research in medical sciences is recognized as one of the most important sources of novel findings that can be applied to address challenges within healthcare systems. However, findings from recent studies investigating barriers to the utilization of results reported in student theses indicate that multiple factors hinder the practical implementation of research outcomes.

These barriers fall into four main categories: those related to researchers and the research itself, those associated with organizational and managerial environments, those concerning healthcare professionals and staff, and those linked to policy and regulations. The present study revealed several significant barriers related to researchers and the research process that impede the use of research findings. These include researcher demotivation, low research quality, misalignment with practical healthcare needs, and delays in disseminating results. In line with these findings, Dadipoor et al. also demonstrated that lack of motivation among academic authorities and faculty members constitutes the largest proportion of research-related barriers, respectively [18]. It appears that a misalignment of incentives exists between supervisors and students. This misalignment of motivations often leads to research that is theoretical, non-applied, and disconnected from practical needs. The present analysis suggests that the mere identification of research-related barriers is insufficient unless coupled with a robust assessment of their causal relationships and the underlying systemic mechanisms. A deeper understanding of the dynamic interactions among these factors and an exploration of their structural root causes are paramount. This more comprehensive analysis is a necessary prerequisite for formulating effective strategies and evidence-based policies.

Furthermore, the findings indicated that the low quality of some theses acts as a major barrier to the clinical application of their results. Weak study designs, inappropriate sampling methods, inadequate data analysis, and failure to adhere to international scientific standards collectively undermine the validity and credibility of reported findings. This not only limits the practical application of research but also erodes trust in student-generated evidence. Similarly, Mokhtari et al. reported that student research may be compromised by technical limitations, poor methodological quality, and confounding factors that affect study outcomes [19].

Currently, educational policies in Iran remain largely non-applied in nature. Both faculty and students perceive the primary purpose of thesis work as mastering research methodology, rather than generating actionable knowledge. The medical education system continues to emphasize knowledge production over knowledge translation and utilization. Courses such as “Knowledge Translation,” “Health Innovation,” or “Implementation Project Management” are absent from the curricula, further reinforcing this gap [20]. The findings indicate that the limited application of research findings in clinical practice stems from a systemic and multidimensional gap. Methodological weaknesses in scholarly works—such as flawed study designs, unrepresentative sampling, and inadequate data analysis—directly undermine the scientific credibility and generalizability of results. Concurrently, prevailing educational policies that overemphasize knowledge generation at the expense of translation and implementation further exacerbate this issue. Bridging this divide between knowledge creation and its practical application in healthcare necessitates a concerted, integrated effort addressing both fronts.

The study also emphasized the importance of providing adequate resources and academic supervision to enhance the quality of student research and ensure the validity of findings. In this regard, Mahmoudi et al. found that although students express interest in research, they require greater support and mentorship to conduct high-quality studies [21]. Notably, interviews in the present study revealed that many theses are designed without considering the actual needs of the healthcare system or the target population. This disconnect means that even methodologically sound findings may lack practical applicability. Therefore, strengthening communication and collaboration between students, researchers, and healthcare professionals is essential to align research projects with real-world priorities.

In addition, organizational and managerial barriers were identified as critical factors limiting the implementation of thesis findings. These include misalignment between academic research objectives and clinical service needs, weaknesses in knowledge management systems, and the lack of allocated financial and human resources for implementing research results. For instance, healthcare centers often resist adopting new strategies reported in student theses due to budgetary and time constraints. This highlights that without an integrated and coordinated linkage between academic and clinical sectors; research outputs remain confined to theoretical domains and are rarely translated into practice. Consistent with this, Dadipoor et al. highlighted organizational barriers and limited access to information resources as key contributors to poor research quality in medical sciences [22]. Nejatizadeh et al. also identified insufficient time allocation by faculty members for research supervision as a significant organizational barrier to high-quality student research [23].

Currently, there is a critical weakness in knowledge management systems, with no formal mechanisms in place for translating, summarizing, or disseminating research findings to key stakeholders such as hospital managers or policymakers. As a result, thesis findings remain buried on library shelves, effectively rendering them invisible and unused in decision-making processes [24]. One limitation of this study is its restricted geographical and institutional scope, which may limit the transferability of the findings to other contexts. However, a key strength lies in the use of a qualitative approach that enabled a rich, in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences. The application of maximum variation sampling further enhanced the diversity and depth of perspectives, contributing to data saturation and conceptual richness.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, the underutilization of research findings in the healthcare system cannot be attributed to an isolated factor. Instead, it stems from a complex and interdependent set of barriers operating across four distinct levels: individual (researchers and health professionals), organizational, policy, and the research process itself. At the research level, key obstacles include low methodological quality, misalignment with practical needs, and delayed publication.

At the organizational level, deficiencies manifest as resource constraints, a culture resistant to change, and ineffective knowledge management. The human resource level is characterized by a lack of skills, time pressures, and distrust in evidence, while the macro level is defined by restrictive regulations and insufficient government support.

These factors form a self-reinforcing cycle that perpetuates a systemic failure to translate knowledge into practice. Addressing this multifaceted challenge requires a comprehensive and synergistic strategy that simultaneously focuses on revising research and educational policies, strengthening infrastructural capacity, and cultivating an ecosystem conducive to problem-oriented research and the commercialization of findings.

Only through such an integrated approach can the gap between knowledge production and practical application be effectively bridged to enhance healthcare quality and outcomes.

The non-utilization of thesis findings indicates a structural gap between knowledge production and its application within the education, and healthcare systems. On the researchers’ side, there is a lack of motivation, low research quality, and insufficient focus on real-world needs. On the organizational side, limited resources, non-research-oriented culture, and weak knowledge management hinder implementation. Healthcare professionals and staff also avoid using research findings due to insufficient training, limited time, and lack of trust in research outcomes.

At the systemic level, inappropriate regulations and lack of policy support further widen this gap. To address these challenges, it is recommended to improve the quality and applicability of research, establish knowledge translation units within universities, provide financial support and incentives, strengthen research-oriented organizational culture, reform policies and enhance governmental support, and develop a national platform for sharing research findings.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.MEDSAB.REC.1403.134. The aims of the research were explained to all participants, and written informed consent was obtained. Participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential and that they could discontinue participation at any stage of the study.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Sider (GPT-4.1 mini) to improve readability and language. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the esteemed Deputy of Research and Technology at Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, as well as to the faculty members who participated in this study. We extend our thanks to the Clinical Research Development Unit of Vasei Hospital, affiliated with Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, for their kind support.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the editorial MR, HYM, MF, HA, RCh. SAJ, drafted the initial manuscript. All authors participated in literature review, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and approval of the final version.

Funding

This research was fully supported by Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (grant number 403252).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Background & Objective: Graduate and postgraduate theses in medical sciences aim to identify clinical problems, propose therapeutic strategies, and inform health policies. However, their findings are often not applied in practice. This study explored barriers to implementing results from postgraduate theses.

Materials & Methods: This qualitative study employed a conventional content analysis approach and was conducted from January 31 to March 31, 2025. Ten faculty members participated, selected through purposive sampling until data saturation was achieved. Data were collected via semi-structured, individual interviews and analyzed using Elo and Kyngäs’s method. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, Lincoln and Guba’s criteria—credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability—were applied.

Results: Qualitative data analysis yielded 500 initial codes, which were organized into 63 subcategories, 12 primary categories, and ultimately synthesized into 4 main categories. The four categories included: “barriers related to researchers and research itself”, “barriers related to organizational and managerial environments”, “barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff”, and “barriers related to policy and regulations”. The overarching, abstracted theme was identified as “systematic barriers to the application of research findings in the health system”.

Conclusion: This study identified four main categories of barriers that hinder the use of research evidence in healthcare: researcher- and research-related, organizational, professional, and policy barriers. Overcoming these challenges requires coordinated, multi-level strategies engaging researchers, healthcare providers, managers, and policymakers. Systematic action in these areas can promote evidence-informed decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

As a scientific and applied field, medical sciences play a significant role in improving public health and advancing healthcare systems [1]. Graduate and post-graduate theses in biomedical fields represent essential academic requirements that often generate valuable knowledge and enhance medical service quality [2]. However, many completed research projects remain shelved in libraries or buried in databases, with estimates indicating that 60-80% of student theses never reach practical application [3]. This situation not only wastes financial resources, time, and energy but also results in missed opportunities to improve public health [4].

The process of evidence-based policymaking relies on systematically identifying, evaluating, and applying the best available evidence for decision-making [5]. In this context, student theses constitute a significant knowledge source that could advance the field. The standard workflow for updating medical care involves reviewing literature and evaluating previous research before determining intervention methods [6], which necessitates evidence-based healthcare practices to achieve favorable patient outcomes [7].

The rising healthcare costs underscore the necessity for research-based practice in biomedical sciences, requiring cost-reduction measures across healthcare institutions. Contemporary medical students must demonstrate the benefits of their work to various stakeholders, including society, professions, service recipients, and governmental agencies. These imperative demands greater awareness of the obstacles preventing the application of research in practice. [8].

Addressing current challenges and anticipating future issues through scientific inquiry represents a crucial development pathway [9].

A significant concern in health services remains the gap between known effective treatments and routine care practices. Bridging this gap requires coordinated efforts to implement scientific findings and train skilled researchers [10], while ensuring research validity and reliability through comprehensive and reproducible results [11,12].

Clinical research remains fundamental to medical science advancement, with graduate students bearing substantial research responsibility in medical universities [13]. Consequently, their findings' quality directly influences practical application. The healthcare industry's ongoing digital transformation, characterized by cloud-based data storage and machine learning, is transforming healthcare data into valuable assets [14]. This evolution necessitates student engagement with emerging technologies to expand scientific knowledge. Well-conducted student research can generate high-quality, evidence-based knowledge that benefits decision-makers and reduces resource waste [15].

Previous research has identified various implementation barriers.

Latifi et al. highlighted knowledge stagnation, poor resource utilization, unpublished results, and low research quality in nursing [16].

Azizian et al. found that dental students faced research skill deficiencies, methodological knowledge gaps, statistical unfamiliarity, and limited information access. Insufficient research skills and inadequate resource access were identified as the primary individual and organizational barriers, respectively [17]. Research-active students predominantly reported organizational barriers, while non-research students cited personal obstacles [18].

Generally, graduate research in medical sciences aims to identify clinical problems, develop innovative therapies, and improve health policies [8].

Organizational support deficiencies and decision-making authority limitations have been identified as research utilization barriers [10]. The persistent underutilization of research results represents both missed opportunities and weaknesses in medical research management systems [18].

Previous studies have primarily investigated research barriers from faculty and researchers' perspectives, with limited attention to research utilization obstacles. This study addresses this gap by focusing on knowledge production-application disconnects.

Therefore, identifying existing barriers to implementing graduate research findings and developing effective strategies to overcome them becomes imperative. Employing qualitative methods, this investigation explores faculty members' experiences and perspectives to extract key themes and understand contextual nuances. The study aims to generate new knowledge and offer practical clinical guidance by identifying barriers to the application of graduate and postgraduate thesis findings.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This qualitative study employed a conventional content analysis approach, as outlined by Elo and Kyngäs from January, 31, 2025 to March, 31, 2025, and was conducted at the faculty members of the faculties of Nursing and Midwifery, Allied Health Sciences, and the Public Health Department at Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran Participants and sampling Participants were recruited through purposive sampling with maximum variation to ensure representation of a wide range of experiences and characteristics relevant to the research question.

The inclusion criteria were having already supervised at least one master’s thesis; having had its findings published in at least one scholarly article; and willingness to participate and share personal experiences.

The sole exclusion criterion was withdrawal of consent at any stage of the research.

In keeping with qualitative principles, the number of participants was not fixed in advance but was determined by the richness and depth of the data obtained; recruitment continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, defined as the point at which no new codes were identified and subsequent interviews merely confirmed previously collected data. For planning purposes, an initial range of 40–90 individuals per group had been anticipated.

Tools/Instruments

Semi-structured in-depth interview was used for data collection. Maximum variation sampling (considering age, gender, work experience, professional experience, educational level, managerial experience, and the number of these supervised) was employed to select the participants.

Data collection methods

Data were collected through semi structured, in depth interviews, a method valued in qualitative research for its flexibility and ability to elicit rich descriptions of lived experience. An interview guide, adapted to each participant group, ensured consistent coverage of key issues.

Data saturation was achieved after eight interviews. No new codes or subcategories emerged in the final two interviews, indicating that data saturation had been reached. The time and location of the interviews were agreed upon between the participants and the interviewer.

The researcher introduced herself at the start of each session, explained the study objectives, obtained written informed consent for participation and audio recording, reassured participants regarding confidentiality, and established rapport before initiating formal questioning. Interviews were conducted in a private setting, audio recorded with permission, transcribed verbatim immediately after completion, and supplemented with field notes. With participants’ consent, the interview commenced with warm-up questions, including the participant's self-introduction, age, work experience, professional academic experience, educational level, managerial experience, and the number of theses they had supervised. Following this, the main portion of the interview began with a general question regarding the obstacles to the application of research findings reported in master's theses. Gradually, more specific questions were asked, such as “What conditions can lead to these issues?”, “What strategies could improve the situation?”, and “What actions did you take as a supervisor?”."

If necessary, further probing questions were asked, such as "Could you explain more about this?", "What happened next?", "What occupied your thoughts?", "How did you feel?", etc.

Each interview session ended with the following two questions: "In your opinion, is there any other question I should have asked but failed to ask?" and "Do you have any questions for me?"

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis proceeded concurrently. Each transcript was read repeatedly to achieve immersion, condensed into initial codes, compared for similarities and differences, grouped into subcategories, merged into broader generic categories, and finally abstracted into a main overarching category. This process followed the stages of open coding, categorization, and abstraction described by Elo and Kyngäs [17]. After multiple rounds of listening, reading, and immersion in the data, an overall picture was obtained, meanings were extracted, key ideas were highlighted, and codes were assigned based on their relationships to one another.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured according to Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability, achieved through prolonged engagement with participants and data, iterative coding and review, member checking (returning transcripts and preliminary codes to participants for verification), peer debriefing with the research team, and maintaining a detailed audit trail documenting the study process from inception to completion. Additional measures included spending sufficient time on data collection and analysis to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants, reviewing the interviews and codes within the research team, building strong rapport with participants to facilitate deeper interviews, engaging in prolonged data processing, reading the interviews multiple times to refine codes, reviewing various stages of analysis in repeated team sessions, and having other colleagues review the codes.

Interviews, codes and extracted categories were given to some experts familiar with qualitative research methods; they were asked to review the coding and analysis methods and provide comments on its accuracy. In controversial cases, discussions were made and consensus was achieved. Different stages of analysis were recorded and described to be used for evaluation by external experts. Data were analyzed using MAXQDA 24 software.

Results

In this qualitative study, a total of 10 semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with faculty members. Participants included six men and four women aged 40 to 60 years, with work experience ranging from 5 to 30 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

Abbreviation: EDC, educational development center.

Qualitative data analysis yielded 500 initial codes, which were organized into 63 subcategories, 12 primary categories, and ultimately synthesized into 4 main categories. The four categories were: ‘barriers related to researchers and research itself,’ ‘barriers related to organizational and managerial environments,’ ‘barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff,’ and ‘barriers related to policy and regulations.’ The overarching, abstracted theme was identified as: “systematic barriers to the application of research findings in the health system” (Table 2).

Table 2. Themes, main categories, subcategories, and initial codes

Barriers related to researchers and research itself

This concept emerged from four primary subcategories: “researcher demotivation”, “quality of research”, “lack of adaptation to practical needs”, and “delay in publishing the results”. This concept reveals that the failure to implement research findings in the health system does not result from a single issue, but from a complex interplay of systemic barriers. These obstacles, categorized as research-related and researcher, managerial and organizational, healthcare professional-related, and legal challenges and policy, are deeply interconnected and often self-reinforcing.

Researcher demotivation: The experiences of participants revealed that the necessary facilities for conducting high-quality research were not provided for them.

Additionally, low research budgets and the high costs of implementing projects often led to a bias in student theses toward questionnaire-based, low-quality projects. The goal became merely publishing a paper rather than applying the findings in a real setting where problems awaited scientific solutions; note the statement below by one participant: "Research work needs money; if it is not provided, the student or his/her supervisor has to pay it out of pocket, and that means that useful work is not undertaken..." (Participant 6)

Quality of research: Some research studies never turn out to be applicable in practice due to their weaknesses of methodology, inappropriate sampling, or dissociation from clinical needs. Participants stated that some of the theses they completed were not of high quality. Contributing factors included supervisors’ busy instructional schedules and lack of time for student research, viewing theses merely as educational exercises, small sample sizes that hampered generalizability, theses not based on real problems or healthcare priorities, goals set for employment or promotion purposes, and students’ hasty selection of topics and completion of research. Even in priority-oriented topics provided by the Ministry of health, research questions were hastily formulated, which tended to reduce their quality; note the statement below by one of the supervisors:

“The thesis constitutes a foundational exercise in research methods. It is a supervised learning process in which the student acquires research competencies systematically. Given that students are novice researchers with minimal experience, their work cannot be expected to attain perfection..." (Participant 10)

Lack of adaptation to practical needs: Research is often conducted either in laboratory or under certain circumstances that are different from real healthcare settings; accordingly, most of the results obtained in student dissertations tend to become less applicable to real settings. Participants stated that there was little attention paid to research arising from real problems, and the actual problems in clinical practice and society were not addressed. Thesis topics are often rooted in the latest published articles, but action research is not utilized due to students' unfamiliarity with this type of research. Consequently, thesis research does not precisely correspond to the practical needs of society and clinical practice, hindering the use of obtained results in practice; note the statement below by one of the professors:

"The theses we supervise are not based on the actual problems of the wards; the students come to us with a research title borrowed from a newly published article, and we approve it..." (Participant 7)

Delay in publishing the results: Participants stated that sometimes research is published long after it is completed, and by that time, the obtained results lose their relevance and novelty. For them, that was because journals tended to accept contradictory results while they are less interested in insignificant findings. Other reasons included the student researchers’ reluctance to publish articles extracted from their theses and supervisors’ lack of time to assist students in publication. However, care provision should be evidence-based and rooted in scientific findings. This requires systematic reviews and the inclusion of research findings in reference books or ministry declarations, which altogether delays public accessibility to those findings: note the statement below by one of the supervisors.

“The student works on the thesis and then abandons it...; the professor, who also doesn't have time to publish, might get around to publishing it a few years later...” (Participant 1)

Barriers related to organizational and managerial environments

This concept emerged from three primary subcategories: “lack of financial and infrastructural resources”, “organizational structure and culture”, and “weaknesses in knowledge management”. The obstacles within the ‘organizational and managerial environment’ represent some of the most fundamental challenges an organization can face. The three primary barriers—a lack of financial and infrastructural resources, an ineffective organizational structure and culture, and deficiencies in knowledge management—are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

This interplay traps the organization in a vicious cycle, severely impeding its capacity for innovation, adaptation, and long-term goal achievement. Consequently, overcoming these challenges requires a comprehensive, simultaneous approach addressing all three dimensions.

Lack of financial and infrastructural resources: Participants stated that the implementation of research findings required adequate financial resources, equipment, and infrastructure, which are often not available to junior researchers; note the statement below by one of the participants:

"For example, health education theses require the preparation of software or gamification designs, etc., which is very costly, and effective research cannot be conducted under these conditions..." (Participant 4)

Organizational structure and culture: Many healthcare centers and organizations have traditional structures with no flexibility to accommodate and implement changes. A culture of resistance to change can also prevent the implementation of new findings. Participants stated that in the organizational culture of medical sciences which are resistance to change, the emphasis on publishing articles and non-applied indicators such as the effect of H-index in a professor's promotion, the lengthened process of approving study designs, the implementation of quick-return theses, and the lenience of research councils towards students to conduct high-quality and applied studies are among the reasons for the low quality of theses and, ultimately, their non-applicability. For instance, note the statement below:

“Contemporary academic systems often prioritize quantitative research output, such as publication count and H-index, in hiring and promotion decisions. This can create an environment where the perceived impact of these metrics outweighs considerations of a study's intrinsic scholarly or practical utility..." (Participant 8)

Weaknesses in knowledge management: Participants stated that the organization does not have an effective knowledge management system to identify, organize, and implement scientific knowledge in practice. Participants noted several factors contributing to weak knowledge management, which hinder the application of research results. These included a lack of interdepartmental coordination to present research findings for practical use, managers’ failure to apply results, stakeholders’ lack of engagement with findings, and insufficient consultation with experts on how to use scientific evidence. Consider the statement below by one of the supervisors:

"The current knowledge translation that exists is not accessible to everyone; many people do not even know what it is or where it is. Even the researchers themselves do not have access to the knowledge translation of other universities. Widespread unfamiliarity with KT resources, coupled with institutional barriers that restrict access even for researchers, severely limits the dissemination and utility of scientific evidence..." (Participant 9)

Barriers related to healthcare professionals and staff

This concept emerged from three primary subcategories: “lack of training and skills”, “time constraints”, “lack of trust in research findings”. The barriers at the level of healthcare professionals represent a pivotal challenge in the process of healthcare system transformation. These three core obstacles—deficiencies in training and skills, limited time, and distrust of research evidence—interact in a vicious cycle: insufficient skills foster skepticism toward new evidence, while time constraints exacerbate these issues by preventing meaningful engagement with new knowledge or skill development. Collectively, they pose a major impediment to implementing evidence-based care, compromising service quality. Addressing these interrelated barriers therefore requires a coordinated strategy that targets all three dimensions simultaneously.

Lack of training and skills: Some healthcare staff are not familiar with the necessary knowledge and skills to implement new findings. Participants stated that utilizing thesis findings required certain training and skills because the reported findings were only in the form of numbers, figures, and statistics. The gap between theory and practice lies in how to apply these results, which entails an expert committee to operationalize the findings in society and make the research results publicly available. It further demands holding in-person meetings with researchers to present the findings or report the results from an operational perspective in the form of knowledge translation. Currently, knowledge translation is not available in public media, and stakeholders are even unaware of it; therefore, they require the necessary training in this regard; look at the following statement:

" The technical language of medical research can pose a barrier to clinicians seeking to apply new findings. When confronted with such specialized literature, clinicians often rely on intermediaries to translate the results or provide a concise summary of the core evidence." (Participant 2)

Time constraints: Workers of the healthcare and therapeutic sections often encounter a heavy workload and cannot allocate enough time to study and apply new findings in practice. Participants stated that students have limited time to complete their theses, which can affect the quality of their research. Similarly, healthcare personnel have limited time to use the results of all research findings and study their details due to their heavy workload in hospital wards.

"Sometimes these student researchers are in such a hurry to defend their theses and graduate that they resort to doing anything." (Participant 6)

Lack of trust in research findings: The study participants further stated that one of the significant reasons preventing the use of thesis results is mistrusting the validity or applicability of those results. Poor design and methodology, insufficient supervision by study supervisors and advisors, possibility of data manipulation by some student researchers, inappropriate statistical analysis particularly by non-experts, lack of student engagement in their own research work, outsourcing the work, failure to inform supervisors in a timely manner for supervision, lack of strict supervisors,

alteration of the results, requirements for publication of articles for promotion purposes and publication with imprecise results, and lack of commitment to presenting proper results can account for the mistrust associated with student thesis reports. The statement below can be of interest:

"When neither the thesis advisor nor the project supervisor oversees the research, what do you think will come out of it? Potential consequences include methodological errors, an unfocused research question, and ethical oversights. Without expert guidance, the project is unlikely to achieve its potential contribution to the field and may not fulfill the criteria for a credible academic exercise. Consequently, the project often fails to make a meaningful contribution to the field or meet the standards of a credible academic exercise..." (Participant 4)

Barriers related to policy and regulations

This concept emerged from two primary subcategories: “inappropriate laws” and “lack of governmental support”. Obstacles stemming from 'Policies and Regulations' constitute a critical, overarching framework that shapes other organizational and individual barriers. The two primary subcategories in this domain—inadequate regulations and insufficient institutional support—share a reciprocal and reinforcing relationship. Restrictive regulations constrain the ability of institutions to provide effective support, while a lack of financial and executive backing renders enacted legislation ineffective.

This negative synergy creates an implementation gap that fundamentally impedes the achievement of reform objectives at the ground level. Consequently, breaking this cycle requires the concurrent revision of outdated policies and the provision of concrete, targeted institutional support.

Inappropriate laws: Participants stated that some rules and regulations may prevent the implementation of student research findings.

They highlighted several regulations set by the research council, including the rejection of repetitive study designs—even when such designs are necessary to confirm previous findings, the absence of active collaboration with industry, the lack of a committee to establish genuine research priorities within healthcare sectors, and insufficient discipline and oversight for rigorous thesis monitoring. Collectively, these issues have weakened results and pushed them further from practical application. Note the statement below:

"Well, for study findings to be applicable in clinical practice, it needs to be researched several times in several settings, but the council for postgraduate studies often emphasizes that the research must be innovative..." (Participant 1)

Lack of governmental support: Lack of financial and policy support from the government can hinder the implementation of applied projects. Participants stated that the government can assist by providing arrangements for conducting systematic reviews, providing new protocols to hospitals and health centers, helping in the commercialization of manufactured products, determining the right priorities for conducting applied research, assigning the mission to conduct research in each applied field to a university, and most importantly, providing financial support to researchers in conducting applied research. Consider the following statement:

"For the past few years, incentive policies have decreased, and the funds approved for projects are not at all sufficient, and impactful work can no longer be done. The pathway to clinically applicable research requires validation through repeated studies in diverse settings. Researchers must therefore navigate the challenge of designing studies that are both original and capable of contributing to a robust evidence base…" (Participant 8)

Discussion

Graduate student research in medical sciences is recognized as one of the most important sources of novel findings that can be applied to address challenges within healthcare systems. However, findings from recent studies investigating barriers to the utilization of results reported in student theses indicate that multiple factors hinder the practical implementation of research outcomes.

These barriers fall into four main categories: those related to researchers and the research itself, those associated with organizational and managerial environments, those concerning healthcare professionals and staff, and those linked to policy and regulations. The present study revealed several significant barriers related to researchers and the research process that impede the use of research findings. These include researcher demotivation, low research quality, misalignment with practical healthcare needs, and delays in disseminating results. In line with these findings, Dadipoor et al. also demonstrated that lack of motivation among academic authorities and faculty members constitutes the largest proportion of research-related barriers, respectively [18]. It appears that a misalignment of incentives exists between supervisors and students. This misalignment of motivations often leads to research that is theoretical, non-applied, and disconnected from practical needs. The present analysis suggests that the mere identification of research-related barriers is insufficient unless coupled with a robust assessment of their causal relationships and the underlying systemic mechanisms. A deeper understanding of the dynamic interactions among these factors and an exploration of their structural root causes are paramount. This more comprehensive analysis is a necessary prerequisite for formulating effective strategies and evidence-based policies.

Furthermore, the findings indicated that the low quality of some theses acts as a major barrier to the clinical application of their results. Weak study designs, inappropriate sampling methods, inadequate data analysis, and failure to adhere to international scientific standards collectively undermine the validity and credibility of reported findings. This not only limits the practical application of research but also erodes trust in student-generated evidence. Similarly, Mokhtari et al. reported that student research may be compromised by technical limitations, poor methodological quality, and confounding factors that affect study outcomes [19].

Currently, educational policies in Iran remain largely non-applied in nature. Both faculty and students perceive the primary purpose of thesis work as mastering research methodology, rather than generating actionable knowledge. The medical education system continues to emphasize knowledge production over knowledge translation and utilization. Courses such as “Knowledge Translation,” “Health Innovation,” or “Implementation Project Management” are absent from the curricula, further reinforcing this gap [20]. The findings indicate that the limited application of research findings in clinical practice stems from a systemic and multidimensional gap. Methodological weaknesses in scholarly works—such as flawed study designs, unrepresentative sampling, and inadequate data analysis—directly undermine the scientific credibility and generalizability of results. Concurrently, prevailing educational policies that overemphasize knowledge generation at the expense of translation and implementation further exacerbate this issue. Bridging this divide between knowledge creation and its practical application in healthcare necessitates a concerted, integrated effort addressing both fronts.

The study also emphasized the importance of providing adequate resources and academic supervision to enhance the quality of student research and ensure the validity of findings. In this regard, Mahmoudi et al. found that although students express interest in research, they require greater support and mentorship to conduct high-quality studies [21]. Notably, interviews in the present study revealed that many theses are designed without considering the actual needs of the healthcare system or the target population. This disconnect means that even methodologically sound findings may lack practical applicability. Therefore, strengthening communication and collaboration between students, researchers, and healthcare professionals is essential to align research projects with real-world priorities.

In addition, organizational and managerial barriers were identified as critical factors limiting the implementation of thesis findings. These include misalignment between academic research objectives and clinical service needs, weaknesses in knowledge management systems, and the lack of allocated financial and human resources for implementing research results. For instance, healthcare centers often resist adopting new strategies reported in student theses due to budgetary and time constraints. This highlights that without an integrated and coordinated linkage between academic and clinical sectors; research outputs remain confined to theoretical domains and are rarely translated into practice. Consistent with this, Dadipoor et al. highlighted organizational barriers and limited access to information resources as key contributors to poor research quality in medical sciences [22]. Nejatizadeh et al. also identified insufficient time allocation by faculty members for research supervision as a significant organizational barrier to high-quality student research [23].

Currently, there is a critical weakness in knowledge management systems, with no formal mechanisms in place for translating, summarizing, or disseminating research findings to key stakeholders such as hospital managers or policymakers. As a result, thesis findings remain buried on library shelves, effectively rendering them invisible and unused in decision-making processes [24]. One limitation of this study is its restricted geographical and institutional scope, which may limit the transferability of the findings to other contexts. However, a key strength lies in the use of a qualitative approach that enabled a rich, in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences. The application of maximum variation sampling further enhanced the diversity and depth of perspectives, contributing to data saturation and conceptual richness.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, the underutilization of research findings in the healthcare system cannot be attributed to an isolated factor. Instead, it stems from a complex and interdependent set of barriers operating across four distinct levels: individual (researchers and health professionals), organizational, policy, and the research process itself. At the research level, key obstacles include low methodological quality, misalignment with practical needs, and delayed publication.

At the organizational level, deficiencies manifest as resource constraints, a culture resistant to change, and ineffective knowledge management. The human resource level is characterized by a lack of skills, time pressures, and distrust in evidence, while the macro level is defined by restrictive regulations and insufficient government support.

These factors form a self-reinforcing cycle that perpetuates a systemic failure to translate knowledge into practice. Addressing this multifaceted challenge requires a comprehensive and synergistic strategy that simultaneously focuses on revising research and educational policies, strengthening infrastructural capacity, and cultivating an ecosystem conducive to problem-oriented research and the commercialization of findings.

Only through such an integrated approach can the gap between knowledge production and practical application be effectively bridged to enhance healthcare quality and outcomes.

The non-utilization of thesis findings indicates a structural gap between knowledge production and its application within the education, and healthcare systems. On the researchers’ side, there is a lack of motivation, low research quality, and insufficient focus on real-world needs. On the organizational side, limited resources, non-research-oriented culture, and weak knowledge management hinder implementation. Healthcare professionals and staff also avoid using research findings due to insufficient training, limited time, and lack of trust in research outcomes.