Sun, Feb 22, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 4 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(4): 73-82 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.062

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rajabi Pour S, Ahmadi M, Dadanjani A. Spiritual care competence in nursing students: the predictive roles of spiritual well-being and emotional intelligence. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (4) :73-82

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2465-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2465-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran ,mer.ahmadi@gmail.com

2- Nursing Care Research Center in Chronic Diseases, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran ,

Keywords: spiritual care, spiritual care competency, emotional intelligence, spiritual well-being, nursing students

Full-Text [PDF 543 kb]

(175 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (946 Views)

Full-Text: (18 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Spiritual care is the essence of nursing services and one of the main duties of nurses. Also, spiritual well-being and emotional intelligence are factors affecting the caring behaviors of nurses. This study aimed to check the level of perceived Competence in Spiritual Care (CSC) and to look into the predictive roles of Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) and Emotional Intelligence (EI) among nursing students.

Materials & Methods: This descriptive-correlational research study involved 215 undergraduate nursing students. Participants were recruited using a census sampling way. Data collection took place between May 6 and July 18, 2023, using four standardized instruments: a demographic information checklist, the Scale for Assessment of Nurses' Competencies in Spiritual Care, the Spiritual Well-Being Scale, and the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25, which included independent t-tests, one-way Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA), Pearson's correlation coefficient, and multiple linear regression to look at the relationships among the variables.

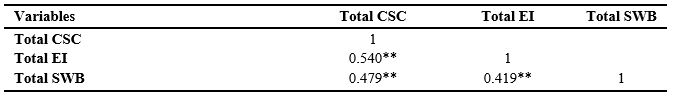

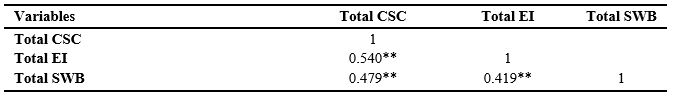

Results: The present study revealed a positive and significant correlation between CSC and EI (p < 0.001, r = 0.54), as well as between CSC and SWB (p < 0.001, r = 0.47). Regression models revealed that EI (β = 0.408, p < 0.001), SWB (β = 0.308, p = 0.004), age (β = -0.126, p = 0.021), and marital status (β = -0.117, p = 0.032) were significant predictors of CSC in nursing students. These variables accounted for 39% of the variance in spiritual care competencies.

Conclusion: EI and SWB have a significant effect on nursing students' ability to give spiritual care to patients. These results stress the significance of including emotional and spiritual growth into nursing education programs. By building these attributes through targeted training and helpful strategies, nursing students can be better prepared to address patients' spiritual needs, promote holistic healing, and improve the overall quality of care in various clinical settings.

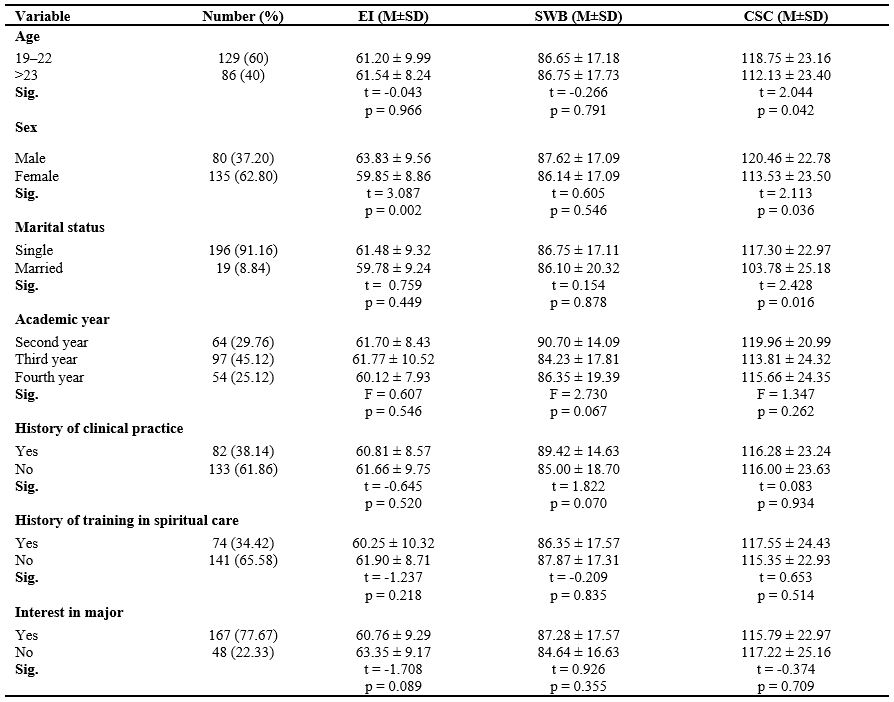

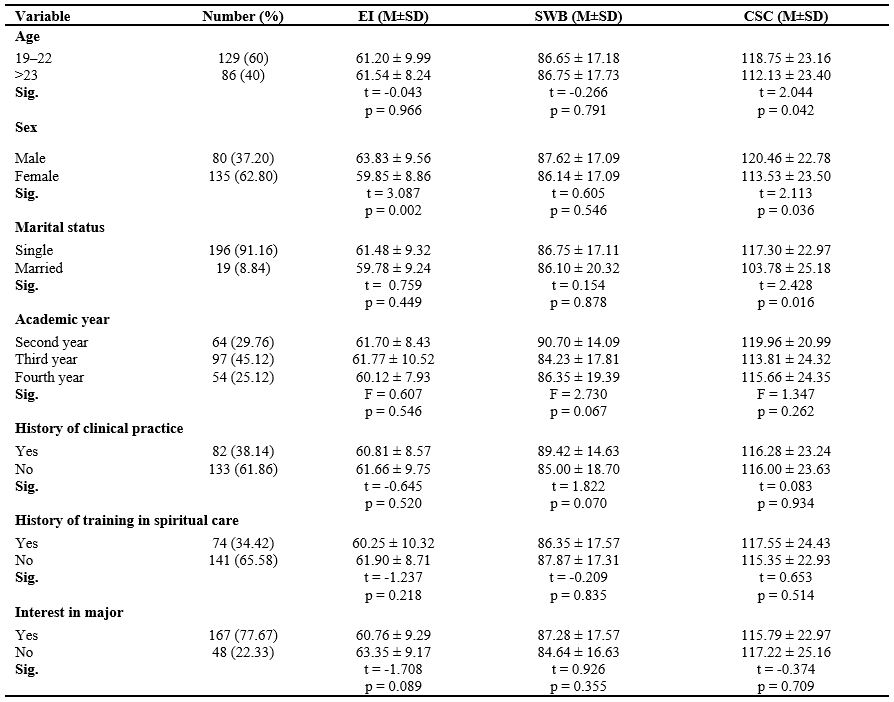

Table 1. Demographic variables of nursing students and their relationship with EI, SWB, and CSC

Table 2. Descriptive data for outcome variables, including CSC, EI, and SWB in nursing students (n = 215)

Note: Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between variables. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being; RWB, religious well-being; EWB, existential well-being.

Table 4. Stepwise multiple linear regression models for predictors of CSC in nursing students

Abbreviations: R², R square; AdjR², adjusted R square; SE, standard error; B, unstandardized coefficient; β, standardized coefficient; p, probability value; CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being.

Discussion

This study looked at the spiritual care competence of nursing students and its association with their SWB and EI. The present study revealed that nursing students showed moderate to high levels of clinical spiritual care competence (CSC), which aligns with previous research carried out in similar educational settings [17, 34, 35]. In contrast, studies involving practicing nurses have reported lower levels of competence [8, 9, 36], likely due to factors such as workload, time constraints, and occupational stress.

Nursing students, by comparison, may perceive themselves as more competent due to reduced clinical responsibilities and greater for reflection during supervised training. The recent inclusion of spiritual care concepts in nursing ethics curricula may have contributed to students' awareness and preparedness in this domain. Also, the cultural significance of spirituality in Iranian society—rooted in religious traditions and ethical norms—appears to enhance students' sensitivity to patients' spiritual needs. The integration of Islamic ethics into both academic and clinical training likely reinforces these values, shaping students' perceptions and self-reported competence in delivering spiritual care. Still, the potential for self-report bias should be acknowledged when explaining these findings. The study found that younger nursing students reported higher levels of spiritual care competence, which is consistent with findings from Yang et al. [11], who watched similar trends among younger nurses. This association may reflect lower levels of academic burnout [20, 28] and greater emotional engagement among students at earlier stages of professional growth [37]. But, due to the limited age range in the current sample, caution is warranted when generalizing these results. Also, unmarried students reported higher CSC scores compared to their married peers. This may be attributed to fewer external responsibilities, such as family obligations, allowing for greater focus on holistic care [23]. Conversely, the dual demands of marital and academic roles may limit the capacity for such involvement among married students [38]. Although age and marital status emerged as significant predictors in the regression analysis, these associations are likely affected by complicated personal and environmental factors. Previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding demographic variables, maybe due to differences in research settings, sampling strategies, and cultural contexts [17, 34, 35]. Further research is needed to look for the mechanisms underlying these relationships. The present study found no significant differences in CSC scores based on academic year, clinical experience, or prior spiritual care education. This finding is consistent with Ahmadi et al. [35], but contrasts with Guo et al. [17], who reported higher competence among students who had received formal spiritual care training. The discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size, curriculum quality, or instructional ways. These findings stress the importance of not only giving spiritual care education but also ensuring its quality and effective implementation. Including experiential learning, mentorship, and simulation-based training may help bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice in this area. The present study revealed a positive and significant correlation between nursing students' spiritual care competence, EI, and SWB. Also, the regression analysis revealed that EI was the strongest predictor of CSC among nursing students, next by SWB. This finding stresses the pivotal role of emotional awareness, regulation, and interpersonal sensitivity in delivering holistic and compassionate care. The positive association between SWB and CSC further suggests that students with deeper spiritual engagement and inner peace may be more attuned to patients' spiritual needs. These results are consistent with previous studies that stress the affect of emotional and spiritual capacities on nursing competence [18, 23, 39, 40]. Our findings also align with Zhang et al.'s research, which showed the mediating role of EI in the relationship between spiritual care competence and core nursing competencies among interns in China [39].

Multiple studies have showed a positive association between nurses' SWB and their competence in giving spiritual care. For instance, nurses with higher SWB tend to show more favorable attitudes toward spiritual care [41] and show greater professional commitment [11]. Wang et al. also reported a strong correlation between SWB and perceived competence among Chinese nurses [42]. Also, SWB appears to make better nurses' sensitivity and responsiveness to patients' spiritual needs through empathetic and value-driven interactions [37, 43]. These findings back up the results of the present study, suggesting that SWB may contribute to better performance and a higher quality of holistic nursing care. As a multidimensional construct including beliefs, values, and emotional experiences, spirituality can shape a nurse's approach to care and increase engagement with patients' spiritual concerns [44, 45]. But, some studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between SWB and the competence to give spiritual care. For instance, Jalali et al. found no significant association between SWB and clinical competence among ICU nurses, suggesting that SWB alone may not be a enough predictor of professional performance [46]. These discrepancies stress the importance of clinical experience and targeted education, highlighting the need for further research to look for the multifaceted factors that affect competence in spiritual care. Given the strong predictive power of EI and SWB, combining these constructs into nursing education should be considered a pedagogical priority. Structured interventions—such as reflective journaling, empathy-based communication exercises, and simulated spiritual care scenarios—can make better students' emotional responsiveness and spiritual sensitivity.

Embedding EI and SWB growth across both theoretical and clinical components of the curriculum may foster holistic competencies that align with patient-centered care models. These strategies are backed up by prior research advocating for emotional intelligence training to make better nursing performance and caregiving behaviors [18, 24, 26, 28, 40].

This study is significant as one of the few to look into the relationship between EI and spiritual care competence among nursing students. But, this study has several limitations that should be considered when explaining the findings.

Although a census sampling approach was employed by distributing the questionnaire to all eligible nursing students, the final sample size was limited to 215 respondents, and no data were available on the characteristics of non-respondents.

The study was carried out at a single university within a specific cultural and religious context in Iran, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other educational or cultural settings.

Also, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, particularly in checking competencies and emotional traits. Future research employing mixed-way approaches—joining self-reports with direct observations and evaluations from clinical educators—is recommended to make better the accuracy of the findings. Also, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot set up causal relationships between emotional intelligence, spiritual well-being, and spiritual care competence. Longitudinal studies across diverse institutions and cultural backgrounds are needed to check and expand upon these results.

Conclusion

This study revealed that EI and SWB are significant predictors of nursing students' competence in giving spiritual care. Students with higher levels of EI and SWB reported greater readiness to address patients' spiritual needs, stressing the importance of building these attributes during nursing education. The findings also showed that younger and unmarried students showed higher levels of spiritual care competence, suggesting that personal characteristics may affect students' perceptions and performance in this area.

These results stress the necessity for nursing curricula to include emotional and spiritual growth into clinical training.

By fostering empathy, emotional regulation, and spiritual sensitivity, educators can more effectively prepare nursing students to give holistic care that addresses both the physical and spiritual needs of patients. This study contributes to the expanding body of evidence that backs up the importance of emotional and spiritual competencies in nursing education and stresses the value of targeted interventions aimed at making better students' caregiving abilities.

Ethical considerations

This research has been approved by the ethics committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (Ethical Code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.062). Ethical considerations, including getting permission from the appropriate authorities, clearly telling the study's objectives to participants, ensuring the confidentiality of data, and obtaining verbal consent from participants, were followed.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

We acknowledge the use of WORDVICE.AI (https://wordvice.ai/proofreading/6c21e242-4286-4ed0-93c7-ea479dd98f86) to proofread some sentences of our work.

Acknowledgment

This study was extracted from a research proposal approved by the Student Research Committee, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (NO:02s8). The researchers appreciate all staff in the "Student Research Committee" and "Research & Technology Chancellor" at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences for their financial support. In addition, the researchers are thankful to all the nursing students who took part in this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared no possible conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

MA and SRP contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection,

and analysis were performed by MA, SRP, and AD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MA and SRP. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MA as a principal investigator, supervised the project.

Funding

This research was funded by Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran under Grant No. 02s8.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For access to more data, please reach out to the corresponding author.

Background & Objective: Spiritual care is the essence of nursing services and one of the main duties of nurses. Also, spiritual well-being and emotional intelligence are factors affecting the caring behaviors of nurses. This study aimed to check the level of perceived Competence in Spiritual Care (CSC) and to look into the predictive roles of Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) and Emotional Intelligence (EI) among nursing students.

Materials & Methods: This descriptive-correlational research study involved 215 undergraduate nursing students. Participants were recruited using a census sampling way. Data collection took place between May 6 and July 18, 2023, using four standardized instruments: a demographic information checklist, the Scale for Assessment of Nurses' Competencies in Spiritual Care, the Spiritual Well-Being Scale, and the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25, which included independent t-tests, one-way Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA), Pearson's correlation coefficient, and multiple linear regression to look at the relationships among the variables.

Results: The present study revealed a positive and significant correlation between CSC and EI (p < 0.001, r = 0.54), as well as between CSC and SWB (p < 0.001, r = 0.47). Regression models revealed that EI (β = 0.408, p < 0.001), SWB (β = 0.308, p = 0.004), age (β = -0.126, p = 0.021), and marital status (β = -0.117, p = 0.032) were significant predictors of CSC in nursing students. These variables accounted for 39% of the variance in spiritual care competencies.

Conclusion: EI and SWB have a significant effect on nursing students' ability to give spiritual care to patients. These results stress the significance of including emotional and spiritual growth into nursing education programs. By building these attributes through targeted training and helpful strategies, nursing students can be better prepared to address patients' spiritual needs, promote holistic healing, and improve the overall quality of care in various clinical settings.

Introduction

Spirituality is a basic aspect of human existence, including values and connections that foster well-being and healing. Its significance in recovery has attracted growing scholarly attention [1]. Spiritual care is vital in nursing practice, as it affects patient responses to illness by addressing their spiritual needs through interventions such as empathy, active listening, and respect for cultural differences [2–4]. The increasing demand for spiritual care stresses the necessity of building spiritual care competence among nurses, beginning in nursing education [5]. Clinical competence is defined as an individual's experience level and readiness to effectively combine knowledge, attitudes, values, beliefs, and skills [6]. Spiritual care competence is characterized as an ongoing active process that combines three elements, namely awareness of human values, empathy for clients, and the ability to tailor individualized interventions to each client [7]. Despite the acknowledged significance of spiritual care, many nurses overlook this aspect, frequently leaving patients' spiritual needs unaddressed [8, 9]. This issue may arise from various factors, including not enough training, excessive workloads, time limitations, cultural diversity, ethical dilemmas, and a reluctance to engage in spiritual care [9, 10]. Several factors can serve as predictors of spiritual attentiveness among nurses and nursing students. Notably, understanding one's own spirituality and possessing strong Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) are crucial for understanding the spiritual needs of others [11, 12]. SWB, defined as a harmonious and combined relationship between inner and external forces, includes two dimensions: religious and existential [13]. The religious dimension pertains to connection with a higher power, while the existential dimension involves seeking life's meaning and purpose [13]. The SWB of the healthcare team plays a crucial role in delivering quality patient care and achieving health goals [14]. Studies have shown that nurses with higher SWB show greater competence and a stronger sense of control [15]. Conversely, impaired SWB has been reported to be associated with negative consequences in nurse-patient relationships and a decline in caregiving behaviors [16]. Also, nurses with higher SWB exhibit positive attitudes towards spirituality and display greater competence in giving spiritual care [11, 12]. Since the formation of spiritual beliefs and values during the nursing education period can affect one's spiritual approach to patients and care delivery [17], looking into the role of SWB in predicting nursing students' competence in giving spiritual care is essential. Another important factor that can be effective in giving care services to patients is Emotional Intelligence (EI) [18]. EI, a subset of social intelligence, includes the ability to monitor, distinguish, and use one's own and others' emotions to guide thoughts and actions [19]. According to the theory of emotional intelligence, this type of intelligence plays a key role in emotion regulation and interpersonal relationships [20]. Nursing is considered an emotional profession that demands that nurses have skills such as problem solving, appropriate decision-making, correct judgment in different clinical situations, the ability to recognize and manage their own and their clients' emotions and feelings, and set up appropriate and empathetic social communication with patients. These abilities are part of the factors that make up emotional intelligence [21, 22]. So, EI has a basic role in effective job performance among nurses [23]. Individuals with high EI possess a strong understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, realistically manage their emotions and actions, and foster empathy and trust [21, 22]. Also, nurses who have higher EI perform better at the work environment [23, 24] and have higher job satisfaction [25]. In addition, studies have shown that EI makes better nurses' caregiving behaviors [26] and enables them to better identify patients' spiritual needs [27]. EI also serves as a significant factor affecting nursing students' clinical performance, helping them effectively manage clinical challenges and make better their leadership and performance skills [28]. So, a rigorous exploration of the impact of EI on spiritual care competence within the nursing student population is warranted. By gaining a deeper understanding of this impact, we can create practical interventions to holistically make better students' competence for the best provision of this type of care. Although numerous studies have looked into the individual effects of SWB and EI on nurses' competence in delivering spiritual care, there is limited research looking at their joined affect on spiritual care competence, particularly among nursing students. Most existing literature puts first practicing nurses, overlooking the formative stage of nursing education where students' values, attitudes, and competencies are built. This gap is critical, as nursing students represent the future workforce, and their preparedness to address patients' spiritual needs can significantly impact the quality of care. Also, the lack of combined educational strategies targeting both emotional and spiritual growth in nursing curricula stresses the need for empirical evidence to tell curriculum design. So, this study aims to look into the predictive roles of emotional intelligence and spiritual well-being in determining nursing students' competence in giving spiritual care, thereby addressing a critical gap in nursing education research.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This research is a cross-sectional study carried out between May 6 and July 18, 2023, at the Faculty of Nursing, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

Participants and sampling

Participants were selected using a census sampling method. Of the 280 nursing students who met the eligibility standards, 65 chose not to take part. As a result, the final sample consisted of 215 students who voluntarily took part in the study. The inclusion standards stipulated that participants must have completed a minimum of two semesters of undergraduate nursing education. This requirement was set up to ensure that students had gotten foundational knowledge of essential care principles and had started their clinical internships in hospital settings.

Tools/Instruments

Nursing students provided information on their age, sex, academic year, marital status, history of training in spiritual care (yes or no), history of clinical practice (yes or no), and interest in the field of nursing (yes or no).

The competence of nursing students in giving spiritual care was checked using the Iranian Scale for Assessment of Nurses' Competencies in Spritual Care (SANCSC), built by Adib-Hajbaghery et al. This scale comprises 32 items across five dimensions: knowledge (4 items); attitudes (3 items); human values (6 items); assessment and implementation of spiritual care (17 items); and self-recognition (2 items). Participants provide ratings for all items using a 5-point Likert scale, where 'always' corresponds to a score of 5 and 'never' corresponds to a score of 1. The total score range possible is from 32 to 160. A score of 118 or above signifies excellent professional proficiency in spiritual care, while scores ranging from 74 to 117 and 73 or less are classified as moderate and not enough competence, respectively. The reliability and validity of the SANCSC were checked by Adib-Hajbaghery et al. According to their research, the scale showed a reliability ranging from 0.75 to 0.93 for the total scale and all subscales, as measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient [29]. In the current study, the reliability of the SANCSC, as measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient, was found to be 0.953.

The Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) was used to check students' EI. This questionnaire was designed and built by Wong & Law [30]. In the present study, the Persian version of the WLEIS, translated and psychometrically validated by Ali Babaei et al. [31], was employed. The questionnaire consists of four subscales: self-emotion perception (4 items), emotion perception of others (4 items), emotion usage (4 items), and emotion regulation (4 items). Students' answers were checked using a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score of the WLEIS falls between 16 and 80, with a higher score suggesting a higher level of EI in nursing students. The score is divided into three categories: low EI (16–31.99), moderate EI (32–47.99), and high EI (48-80). In Wong's study, the questionnaire's reliability was documented as 0.89 [30]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were checked by Ali Babaei et al. [31]. In the present research, the WLEIS showed satisfactory reliability with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.90. The SWB of nursing students was measured using the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS). The scale was made by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1991 and includes 20 items divided into two categories: Religious Wellbeing (RWB) with 10 items, and Existential Wellbeing (EWB) with 10 items. Students rate their responses on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total score can range from 20 to 120, with a higher score reflecting greater SWB [32]. The scale's score is divided into three tiers: low (20-40), moderate (41-99), and high level (100-120) of SWB. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the SWBS have been checked by Biglari Abhari et al [33]. In this research, the scale's reliability was deemed acceptable with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85.

Data collection methods

To collect data, the questionnaire links accompanied by an informed consent form outlining the study's objectives, procedures, and participants' rights were distributed via a Google survey through official university channels and class groups hosted on social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Eita, and Telegram. Faculty members directly disseminated the survey to student groups through these platforms. To ensure data quality, the questionnaire was designed to prevent incomplete submissions. Importantly, to check that third-semester nursing students had completed their clinical coursework and were familiar with basic care concepts, the survey link was distributed electronically at the end of the semester. This timing ensured that participants had already gone through the needed clinical training prior to completing the questionnaire, thereby making better the relevance and reliability of their responses.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS version 22 software. The normality of the primary continuous variables was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, given a sample size of 215 participants. The results showed that the SWB variable had a p-value of 0.09, suggesting a normal distribution. In contrast, the p-values for spiritual care competence and EI were both 0.05, which is at the threshold of significance. Considering the large sample size and the visual inspection of histograms and Q–Q plots, the distributions were deemed about normal. As a result, parametric statistical tests were employed in the analysis. Specifically, independent samples t-tests and one-way Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA) were employed to compare the mean scores of spiritual care competence, SWB, and EI across various demographic subgroups. The correlation between these variables was looked at using a correlation matrix with Pearson correlation coefficients. Also, stepwise-selection multiple linear regression analyses were carried out to determine predictors of spiritual care competence among nursing students, with a significance level set at P < 0.05 for entry.

Results

The study included 215 nursing students with a mean age of 22.94 years. Most participants were female (62.8%), 38.1% had prior clinical experience, and 34.4% had received training in giving spiritual care (Table 1).

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This research is a cross-sectional study carried out between May 6 and July 18, 2023, at the Faculty of Nursing, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

Participants and sampling

Participants were selected using a census sampling method. Of the 280 nursing students who met the eligibility standards, 65 chose not to take part. As a result, the final sample consisted of 215 students who voluntarily took part in the study. The inclusion standards stipulated that participants must have completed a minimum of two semesters of undergraduate nursing education. This requirement was set up to ensure that students had gotten foundational knowledge of essential care principles and had started their clinical internships in hospital settings.

Tools/Instruments

Nursing students provided information on their age, sex, academic year, marital status, history of training in spiritual care (yes or no), history of clinical practice (yes or no), and interest in the field of nursing (yes or no).

The competence of nursing students in giving spiritual care was checked using the Iranian Scale for Assessment of Nurses' Competencies in Spritual Care (SANCSC), built by Adib-Hajbaghery et al. This scale comprises 32 items across five dimensions: knowledge (4 items); attitudes (3 items); human values (6 items); assessment and implementation of spiritual care (17 items); and self-recognition (2 items). Participants provide ratings for all items using a 5-point Likert scale, where 'always' corresponds to a score of 5 and 'never' corresponds to a score of 1. The total score range possible is from 32 to 160. A score of 118 or above signifies excellent professional proficiency in spiritual care, while scores ranging from 74 to 117 and 73 or less are classified as moderate and not enough competence, respectively. The reliability and validity of the SANCSC were checked by Adib-Hajbaghery et al. According to their research, the scale showed a reliability ranging from 0.75 to 0.93 for the total scale and all subscales, as measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient [29]. In the current study, the reliability of the SANCSC, as measured by Cronbach's alpha coefficient, was found to be 0.953.

The Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) was used to check students' EI. This questionnaire was designed and built by Wong & Law [30]. In the present study, the Persian version of the WLEIS, translated and psychometrically validated by Ali Babaei et al. [31], was employed. The questionnaire consists of four subscales: self-emotion perception (4 items), emotion perception of others (4 items), emotion usage (4 items), and emotion regulation (4 items). Students' answers were checked using a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score of the WLEIS falls between 16 and 80, with a higher score suggesting a higher level of EI in nursing students. The score is divided into three categories: low EI (16–31.99), moderate EI (32–47.99), and high EI (48-80). In Wong's study, the questionnaire's reliability was documented as 0.89 [30]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were checked by Ali Babaei et al. [31]. In the present research, the WLEIS showed satisfactory reliability with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.90. The SWB of nursing students was measured using the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS). The scale was made by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1991 and includes 20 items divided into two categories: Religious Wellbeing (RWB) with 10 items, and Existential Wellbeing (EWB) with 10 items. Students rate their responses on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total score can range from 20 to 120, with a higher score reflecting greater SWB [32]. The scale's score is divided into three tiers: low (20-40), moderate (41-99), and high level (100-120) of SWB. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the SWBS have been checked by Biglari Abhari et al [33]. In this research, the scale's reliability was deemed acceptable with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85.

Data collection methods

To collect data, the questionnaire links accompanied by an informed consent form outlining the study's objectives, procedures, and participants' rights were distributed via a Google survey through official university channels and class groups hosted on social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Eita, and Telegram. Faculty members directly disseminated the survey to student groups through these platforms. To ensure data quality, the questionnaire was designed to prevent incomplete submissions. Importantly, to check that third-semester nursing students had completed their clinical coursework and were familiar with basic care concepts, the survey link was distributed electronically at the end of the semester. This timing ensured that participants had already gone through the needed clinical training prior to completing the questionnaire, thereby making better the relevance and reliability of their responses.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS version 22 software. The normality of the primary continuous variables was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, given a sample size of 215 participants. The results showed that the SWB variable had a p-value of 0.09, suggesting a normal distribution. In contrast, the p-values for spiritual care competence and EI were both 0.05, which is at the threshold of significance. Considering the large sample size and the visual inspection of histograms and Q–Q plots, the distributions were deemed about normal. As a result, parametric statistical tests were employed in the analysis. Specifically, independent samples t-tests and one-way Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA) were employed to compare the mean scores of spiritual care competence, SWB, and EI across various demographic subgroups. The correlation between these variables was looked at using a correlation matrix with Pearson correlation coefficients. Also, stepwise-selection multiple linear regression analyses were carried out to determine predictors of spiritual care competence among nursing students, with a significance level set at P < 0.05 for entry.

Results

The study included 215 nursing students with a mean age of 22.94 years. Most participants were female (62.8%), 38.1% had prior clinical experience, and 34.4% had received training in giving spiritual care (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic variables of nursing students and their relationship with EI, SWB, and CSC

Note: T-test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare participants based on quantitative demographic variables (n = 215).

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; %, percentage; p, probability-value; n, number of participants; CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; %, percentage; p, probability-value; n, number of participants; CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being.

The distribution of EI, SWB, and CSC levels is presented in Table 2. The majority of students (94.9%) showed high EI, while 91.2% reported moderate SWB and 8.8% high SWB. Regarding CSC, 51.2% of students reported favorable competence, 45.6% moderate, and only 3.3% poor competence. According to Table 1, significant differences in CSC scores were seen based on age, gender, and marital status (p < 0.05). Also, EI scores differed significantly by gender (p = 0.002). Students with prior clinical experience scored significantly higher in the RWB dimension of SWB (p = 0.008), and those with greater interest in their major showed higher scores in the emotional perception of others (a subscale of EI) (p = 0.03).

Table 2. Descriptive data for outcome variables, including CSC, EI, and SWB in nursing students (n = 215)

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being; RWB, religious well-being; EWB, existential well-being.

A correlation matrix revealed strong positive relationships between CSC and both EI and SWB, including all subcomponents (Table 3). Hierarchical multiple regression analysis identified EI as the strongest predictor of CSC (β = 0.540, p < 0.001), next by SWB (β = 0.307, p < 0.001). Age (β = -0.147, p = 0.007) and marital status (β = -0.117, p = 0.032) were negatively associated with CSC. The final model explained 39.3% of the variance in CSC (F = 35.638, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3. Correlation matrix between CSC, EI, and SWB in nursing students

Note: Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between variables. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being; RWB, religious well-being; EWB, existential well-being.

Table 4. Stepwise multiple linear regression models for predictors of CSC in nursing students

Abbreviations: R², R square; AdjR², adjusted R square; SE, standard error; B, unstandardized coefficient; β, standardized coefficient; p, probability value; CSC, competence in spiritual care; EI, emotional intelligence; SWB, spiritual well-being.

Discussion

This study looked at the spiritual care competence of nursing students and its association with their SWB and EI. The present study revealed that nursing students showed moderate to high levels of clinical spiritual care competence (CSC), which aligns with previous research carried out in similar educational settings [17, 34, 35]. In contrast, studies involving practicing nurses have reported lower levels of competence [8, 9, 36], likely due to factors such as workload, time constraints, and occupational stress.

Nursing students, by comparison, may perceive themselves as more competent due to reduced clinical responsibilities and greater for reflection during supervised training. The recent inclusion of spiritual care concepts in nursing ethics curricula may have contributed to students' awareness and preparedness in this domain. Also, the cultural significance of spirituality in Iranian society—rooted in religious traditions and ethical norms—appears to enhance students' sensitivity to patients' spiritual needs. The integration of Islamic ethics into both academic and clinical training likely reinforces these values, shaping students' perceptions and self-reported competence in delivering spiritual care. Still, the potential for self-report bias should be acknowledged when explaining these findings. The study found that younger nursing students reported higher levels of spiritual care competence, which is consistent with findings from Yang et al. [11], who watched similar trends among younger nurses. This association may reflect lower levels of academic burnout [20, 28] and greater emotional engagement among students at earlier stages of professional growth [37]. But, due to the limited age range in the current sample, caution is warranted when generalizing these results. Also, unmarried students reported higher CSC scores compared to their married peers. This may be attributed to fewer external responsibilities, such as family obligations, allowing for greater focus on holistic care [23]. Conversely, the dual demands of marital and academic roles may limit the capacity for such involvement among married students [38]. Although age and marital status emerged as significant predictors in the regression analysis, these associations are likely affected by complicated personal and environmental factors. Previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding demographic variables, maybe due to differences in research settings, sampling strategies, and cultural contexts [17, 34, 35]. Further research is needed to look for the mechanisms underlying these relationships. The present study found no significant differences in CSC scores based on academic year, clinical experience, or prior spiritual care education. This finding is consistent with Ahmadi et al. [35], but contrasts with Guo et al. [17], who reported higher competence among students who had received formal spiritual care training. The discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size, curriculum quality, or instructional ways. These findings stress the importance of not only giving spiritual care education but also ensuring its quality and effective implementation. Including experiential learning, mentorship, and simulation-based training may help bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice in this area. The present study revealed a positive and significant correlation between nursing students' spiritual care competence, EI, and SWB. Also, the regression analysis revealed that EI was the strongest predictor of CSC among nursing students, next by SWB. This finding stresses the pivotal role of emotional awareness, regulation, and interpersonal sensitivity in delivering holistic and compassionate care. The positive association between SWB and CSC further suggests that students with deeper spiritual engagement and inner peace may be more attuned to patients' spiritual needs. These results are consistent with previous studies that stress the affect of emotional and spiritual capacities on nursing competence [18, 23, 39, 40]. Our findings also align with Zhang et al.'s research, which showed the mediating role of EI in the relationship between spiritual care competence and core nursing competencies among interns in China [39].

Multiple studies have showed a positive association between nurses' SWB and their competence in giving spiritual care. For instance, nurses with higher SWB tend to show more favorable attitudes toward spiritual care [41] and show greater professional commitment [11]. Wang et al. also reported a strong correlation between SWB and perceived competence among Chinese nurses [42]. Also, SWB appears to make better nurses' sensitivity and responsiveness to patients' spiritual needs through empathetic and value-driven interactions [37, 43]. These findings back up the results of the present study, suggesting that SWB may contribute to better performance and a higher quality of holistic nursing care. As a multidimensional construct including beliefs, values, and emotional experiences, spirituality can shape a nurse's approach to care and increase engagement with patients' spiritual concerns [44, 45]. But, some studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between SWB and the competence to give spiritual care. For instance, Jalali et al. found no significant association between SWB and clinical competence among ICU nurses, suggesting that SWB alone may not be a enough predictor of professional performance [46]. These discrepancies stress the importance of clinical experience and targeted education, highlighting the need for further research to look for the multifaceted factors that affect competence in spiritual care. Given the strong predictive power of EI and SWB, combining these constructs into nursing education should be considered a pedagogical priority. Structured interventions—such as reflective journaling, empathy-based communication exercises, and simulated spiritual care scenarios—can make better students' emotional responsiveness and spiritual sensitivity.

Embedding EI and SWB growth across both theoretical and clinical components of the curriculum may foster holistic competencies that align with patient-centered care models. These strategies are backed up by prior research advocating for emotional intelligence training to make better nursing performance and caregiving behaviors [18, 24, 26, 28, 40].

This study is significant as one of the few to look into the relationship between EI and spiritual care competence among nursing students. But, this study has several limitations that should be considered when explaining the findings.

Although a census sampling approach was employed by distributing the questionnaire to all eligible nursing students, the final sample size was limited to 215 respondents, and no data were available on the characteristics of non-respondents.

The study was carried out at a single university within a specific cultural and religious context in Iran, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other educational or cultural settings.

Also, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, particularly in checking competencies and emotional traits. Future research employing mixed-way approaches—joining self-reports with direct observations and evaluations from clinical educators—is recommended to make better the accuracy of the findings. Also, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot set up causal relationships between emotional intelligence, spiritual well-being, and spiritual care competence. Longitudinal studies across diverse institutions and cultural backgrounds are needed to check and expand upon these results.

Conclusion

This study revealed that EI and SWB are significant predictors of nursing students' competence in giving spiritual care. Students with higher levels of EI and SWB reported greater readiness to address patients' spiritual needs, stressing the importance of building these attributes during nursing education. The findings also showed that younger and unmarried students showed higher levels of spiritual care competence, suggesting that personal characteristics may affect students' perceptions and performance in this area.

These results stress the necessity for nursing curricula to include emotional and spiritual growth into clinical training.

By fostering empathy, emotional regulation, and spiritual sensitivity, educators can more effectively prepare nursing students to give holistic care that addresses both the physical and spiritual needs of patients. This study contributes to the expanding body of evidence that backs up the importance of emotional and spiritual competencies in nursing education and stresses the value of targeted interventions aimed at making better students' caregiving abilities.

Ethical considerations

This research has been approved by the ethics committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (Ethical Code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.062). Ethical considerations, including getting permission from the appropriate authorities, clearly telling the study's objectives to participants, ensuring the confidentiality of data, and obtaining verbal consent from participants, were followed.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

We acknowledge the use of WORDVICE.AI (https://wordvice.ai/proofreading/6c21e242-4286-4ed0-93c7-ea479dd98f86) to proofread some sentences of our work.

Acknowledgment

This study was extracted from a research proposal approved by the Student Research Committee, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (NO:02s8). The researchers appreciate all staff in the "Student Research Committee" and "Research & Technology Chancellor" at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences for their financial support. In addition, the researchers are thankful to all the nursing students who took part in this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared no possible conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

MA and SRP contributed to the study's conception and design. Material preparation, data collection,

and analysis were performed by MA, SRP, and AD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MA and SRP. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MA as a principal investigator, supervised the project.

Funding

This research was funded by Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran under Grant No. 02s8.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For access to more data, please reach out to the corresponding author.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2025/04/25 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2025/10/18

Received: 2025/04/25 | Accepted: 2025/09/28 | Published: 2025/10/18

References

1. de Brito Sena MA, Damiano RF, Lucchetti G, Peres MFP. Defining spirituality in healthcare: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Front Psychol. 2021;12:756080. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.756080] [PMID] []

2. Hawthorne DM, Gordon SC. The invisibility of spiritual nursing care in clinical practice. J Holist Nurs. 2020;38(1):147-55. [DOI:10.1177/0898010119889704] [PMID]

3. Connerton CS, Moe CS. The essence of spiritual care. Creat Nurs. 2018;24(1):36-41. [DOI:10.1891/1078-4535.24.1.36] [PMID]

4. Khalajinia Z, Heidari A. Explaining the perception of spiritual care from the perspective of health personnel: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:599. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_599_20] [PMID] []

5. Sedighie L, Akin Abadi AS, Ahmadi M, Shirozhan S, Rassouli M. An overview of the status of spiritual care in nursing education in Iran and the world. Afr J Nurs Midwifery. 2021;23(2). [DOI:10.25159/2520-5293/9783]

6. Fukada M. Nursing competency: Definition, structure and development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018;61(1):1-7. [DOI:10.33160/yam.2018.03.001] [PMID] []

7. Sarrión-Bravo JA, González-Aguña A, Abengózar-Muela R, et al. Competence in spiritual and emotional care: Learning outcomes for the evaluation of nursing students. Healthcare. 2022;10(10):2062. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10102062] [PMID] []

8. Adib-Hajbaghery M, Zehtabchi S, Fini IA. Iranian nurses' professional competence in spiritual care in 2014. Nurs Ethics. 2017;24(4):462-73. [DOI:10.1177/0969733015600910] [PMID]

9. Momeni G, Hashemi MS, Hemati Z. Barriers to providing spiritual care from a nurses' perspective: a content analysis study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2022;27(6):575-80. [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_422_21] [PMID] []

10. Green A, Kim-Godwin YS, Jones CW. Perceptions of spiritual care education, competence, and barriers in providing spiritual care among registered nurses. J Holist Nurs. 2020;38(1):41-51. [DOI:10.1177/0898010119885266] [PMID]

11. Yang SH, Tsan YT, Hsu WT, Lin YC, Lin CS, Chen LC. et al. Association between self-efficacy, spiritual well-being and the willingness to provide spiritual care among nursing staff in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):299. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01978-x] [PMID] []

12. Jafari M, Fallahi-Khoshknab M. Competence in providing spiritual care and its relationship with spiritual well-being among Iranian nurses. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:388. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_203_21] [PMID] []

13. Ghaderi A, Tabatabaei SM, Nedjat S, Javadi M, Larijani B. Explanatory definition of the concept of spiritual health: a qualitative study in Iran. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2018;11:3.

14. Naservand A, Elahi N, Dashtebozorg B, Cheraghian B. The relationship between spiritual health and clinical competency of nurses in teaching hospitals of Ahvaz Jundishapur university of medical sciences (2017). Educ Ethics Nurs. 2022;11(1-2):1-8.

15. Shamsi F, Pakdaman M, Malekpour N. The relationship between spiritual health and job stress of nurses in selected teaching hospitals in Yazd in 2020. J Evid Based Health Policy Manag Econ. 2022;6(3). [DOI:10.18502/jebhpme.v6i3.10862]

16. Abdian T, Rahimi Z, Shadfard Z, Dowlatkhah H, Mardaneh A. Effect of spiritual health in the quality of nursing care for patients with COVID-19. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2024;23(2):463-70. [DOI:10.3329/bjms.v23i2.72173]

17. Guo Z, Zhang Y, Li P, Zhang Q, Shi C. Student nurses' spiritual care competence and attitude: an online survey. Nurs Open. 2023;10(3):1811-20. [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1441] [PMID] []

18. da Costa Martins MD, Rodrigues AP, Marques CD, Carvalho RM. Do spirituality and emotional intelligence improve the perception of the ability to provide care at the end of life? The role of knowledge and self-efficacy. Palliat Support Care. 2024;22(5):1109-17. [DOI:10.1017/S1478951524000257] [PMID]

19. Raghubir AE. Emotional intelligence in professional nursing practice: a concept review using Rodgers's evolutionary analysis approach. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018;5(2):126-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.03.004] [PMID] []

20. Xu J, Zhang L, Ji Q, et al. Nursing students' emotional empathy, emotional intelligence and higher education-related stress: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):437. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-023-01607-z] [PMID] []

21. Jafari J, Nassehi A, Zareez M, Dadkhah S, Saberi N, Jafari M. Relationship of spiritual well-being and emotional intelligence among Iranian nursing students. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2021;15(6):1634-40. [DOI:10.53350/pjmhs211561634]

22. Masoudi K, Alavi A. Relationship between nurses' emotional intelligence and clinical decision-making. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2021;29(1):14-22. [DOI:10.30699/ajnmc.29.1.14]

23. Ranjdoust S. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and emotional intelligence with performance of female nurses in Tabriz hospitals in 2018. J Pizhuhish dar Din va Salamat. 2020;6(1):19-35.

24. Pérez-Fuentes MDC, Molero Jurado MdM, Gázquez Linares JJ, Oropesa Ruiz NF. The role of emotional intelligence in engagement in nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):1915. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15091915] [PMID] []

25. Soto-Rubio A, Giménez-Espert MC, Prado-Gascó V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses' health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7998. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17217998] [PMID] []

26. Khademi E, Abdi M, Saeidi M, Piri S, Mohammadian R. Emotional intelligence and quality of nursing care: a need for continuous professional development. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2021;26(4):361-7. [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_268_19] [PMID] []

27. Sabanciogullari S, Çatal N, Doğaner F. Comparison of newly graduated nurses' and doctors' opinions about spiritual care and their emotional intelligence levels. J Relig Health. 2020;59(3):1220-32. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-019-00760-7] [PMID]

28. Budler LC, Gosak L, Vrbnjak D, Pajnkihar M, Štiglic G. Emotional intelligence among nursing students: Findings from a longitudinal study. Healthcare. 2022;10(10):2032. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10102032] [PMID] []

29. Adib-Hajbaghery M, Zehtabchi S. Developing and validating an instrument to assess the nurses' professional competence in spiritual care. J Nurs Meas. 2016;24(1):15-27. [DOI:10.1891/1061-3749.24.1.15] [PMID]

30. Wong CS, Law KS. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: an exploratory study. Leadersh Q. 2002;13(3):243-74. [DOI:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1]

31. Ali Babaei G, Rahimi H, Nabizadeh S, Abdollahi Moghadam M, Ramezani S, Shad Gahraz S. Validation of Wang and Law emotional intelligence scale. Cult Islam Univ. 2024;14(51):139-64.

32. Paloutzian RF, Ellison CW. Manual for the spiritual well-being scale. Nyack (NY): Life Advance; 1991.

33. Biglari Abhari M, Fisher JW, Kheiltash A, Nojomi M. Validation of the Persian version of spiritual well-being questionnaires. Iran J Med Sci. 2018;43(3):276-85.

34. Asgari M, Pouralizadeh M, Pashaki NJ, et al. Perceived spiritual care competence and the related factors in nursing students during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2022;17:100488. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100488] [PMID] []

35. Ahmadi M, Estebsari F, Poormansouri S, Jahani S, Sedighie L. Perceived professional competence in spiritual care and predictive role of spiritual intelligence in Iranian nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;57:103227. [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103227] [PMID]

36. Anshasi HA, Fawaz M, Aljawarneh YM, Alkhawaldeh JfM. Exploring nurses' experiences of providing spiritual care to cancer patients: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):207. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01830-2] [PMID] []

37. Mangolian Shahrbabaki P, Nouhi E. Explaining professionalism and professional socialization process in nursing students. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2023;12(1):1-8. [DOI:10.34172/jqr.2023.01]

38. Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, Ghose N, Moore M, Ali MK. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469. [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469] [PMID] []

39. Zhang Z, Zhang X, Fei Y, Zong X, Wang H, Xu C, et al. Emotional intelligence as a mediator between spiritual care-giving competency and core competencies in Chinese nursing interns: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(6):367. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-023-07839-8] [PMID] []

40. Kaur D, Sambasivan M, Kumar N. Impact of emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence on the caring behavior of nurses: a dimension-level exploratory study among public hospitals in Malaysia. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28(4):293-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.01.006] [PMID]

41. Chiang YC, Lee HC, Chu TL, Han CY, Hsiao YC. The impact of nurses' spiritual health on their attitudes toward spiritual care, professional commitment, and caring. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(3):215-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.outlook.2015.11.012] [PMID]

42. Wang Z, Zhao H, Zhang S, et al. Correlations among spiritual care competence, spiritual care perceptions and spiritual health of Chinese nurses: a cross-sectional correlational study. Palliat Support Care. 2022;20(2):243-54. [DOI:10.1017/S1478951521001966] [PMID]

43. Rabiei Vaziri M, Jaramillo J, Almagharbeh WT, Khajehhasani T, Dehghan M. Spiritual care competency and spiritual sensitivity among nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025;24:884. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-025-03549-0] [PMID] []

44. Heidari A, Afzoon Z, Heidari M. The correlation between spiritual care competence and spiritual health among Iranian nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):277. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-022-01056-0] [PMID] []

45. Shen YH, Hsiao YC, Lee MT, Hsieh CC, Yeh SH. The spiritual health status and spiritual care behaviors of nurses in intensive care units and related factors. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2018;65(6):67-77.

46. Jalali A, Rahmati M, Dastmozd B, Salari N, Bazrafshan MR. Relationship between spiritual health and clinical competency of nurses working in intensive care units. J Health Sci Surveill Syst. 2019;7(4):183-7

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |