Mon, Dec 29, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 3 (2025)

JMED 2025, 18(3): 47-57 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.197

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kharaghani R, Ahmadnia E, Mousavi E, Norouzi Z. The efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on feeling of inferiority and academic engagement of midwifery students: a randomized controlled trial. JMED 2025; 18 (3) :47-57

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2411-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2411-en.html

1- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran ,zahranorouzi23178@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran

3- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran ,

Keywords: counseling, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, inferiority, academic engagement, midwifery students

Full-Text [PDF 582 kb]

(389 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1079 Views)

Full-Text: (20 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Midwifery students are more at risk of psychological harm than other students due to their specific professional characteristics. Feeling of inferiority and lack of academic engagement can lead to reduced academic performance and increased psychological problems. This study aimed to investigate the impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on feeling of inferiority and academic engagement among midwifery students.

Materials & Methods: This randomized controlled trial involved 2023-2024. Sixty-four undergraduate midwifery students were selected using a convenience sampling method. After obtaining written informed consent, the students were randomly assigned to two groups: one intervention group and one control group, each consisting of 32 participants. The intervention consisted of eight 60-minute sessions (once a week) of group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. The control group did not receive any intervention. The research tools included a demographic checklist, Yao et al. Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire and Schaufeli et al. Academic Engagement Questionnaire. The questionnaires were completed by the participants in three stages: before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and one month after the intervention. Relevant statistical tests, using SPSS version 16, were employed to analyze the data.

Results: The results showed that after the intervention, the mean scores of feeling of inferiority and academic engagement between the intervention and control groups were significantly different (p < 0.05). In the intervention group, the mean of overall feeling of inferiority before the intervention was 58.12 ± 24.06; after the intervention, it decreased to 52.59 ± 21.13 and at follow-up, it further declined to 51.55 ± 17.30. In terms of overall academic engagement, the mean scores before the intervention were 53.47 ± 9.74, which changed to 58.21 ± 7.22 after the intervention and increased slightly to 58.62 ± 7.40 at follow-up. For the control group, the mean scores for general feeling of inferiority were as follows: before the intervention, it was 69.38 ± 26.73; after the intervention, it was 73.75 ± 28.06; and at follow-up, it was 73.59 ± 22.11. Regarding general academic engagement, the scores were 49.38 ± 4.31 before the intervention, 48.94 ± 4.50 after the intervention, and 47.84 ± 3.06 at follow-up.

Conclusion: Based on the study's findings, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is recommended to enhance students' feeling of inferiority and academic engagement. It seems that teaching this counseling method to students in the form of a workshop will help them deal with academic and clinical problems more efficiently.

Introduction

Students are the spiritual backbone of society and the future architects of our nation. The importance of the field of midwifery is evident through maternal and neonatal outcomes, which serve as indicators of health and quality of life among countries [1]. Midwifery students, as the future midwives of the country, play a vital role in promoting maternal and neonatal health, as well as encouraging childbearing. However, medical students often face a higher risk of psychological harm compared to their peers due to unique challenges. These challenges include the mental and emotional pressures of the hospital environment, difficulties in managing patients' issues, and uncertainty about their career futures [2]. Among paramedical students, the highest levels of stress are found in the midwifery group, particularly about unpleasant emotions, clinical experiences, humiliating situations, the educational environment, and interpersonal relationships [3] Feeling of inferiority often stem from a sense of weakness and helplessness, which can persist from childhood and be exacerbated by physical or mental challenges. This can lead to feelings of despair and failure [4]. Increased levels of negative feeling of inferiority in students are directly related to rumination, social anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation [5, 6]. This feeling also causes students to experience a decline in academic performance and achievement, ultimately leading to lower psychological well-being [7-9]. Therefore, approaches such as group counseling based on inferiority management, group psychodrama, and social skills training have been used to reduce students' feeling of inferiority [10-12]. Although feeling of inferiority hurt academic achievement, support from parents, teachers, and peers indirectly affects academic achievement through perceived academic engagement [13]. Schaufeli et al. define academic engagement as a positive, satisfying, and academically relevant state of mind characterized by three dimensions: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Rather than being a momentary, specific state, academic engagement refers to a more enduring and pervasive cognitive-emotional state that is not focused on any specific object, event, person, or behavior [14]. Academic engagement is positively correlated with psychological capital and academic success and negatively correlated with academic burnout [15, 16]. Additionally, students that are more anxious tend to experience poorer sleep quality, which in turn negatively affects their academic engagement [17]. Researchers have reported conflicting results on the effects of mindfulness interventions and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on academic engagement in students [18, 19]. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy introduced by Hayes et al. in 1982. This approach is based on mindfulness, and increasing psychological flexibility is considered one of its primary goals [20]. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy includes six processes: 1- acceptance (being open to unwanted thoughts and feelings as they are), 2- cognitive fusion (withdrawing from unhelpful thoughts and feelings to reduce their dominance over behaviors), 3- present moment awareness (maintaining a voluntary and flexible connection with the present), 4- self as a context (flexible self-concept and perspective-taking), 5- values (clarifying personal values), and 6- committed action (creating behavioral patterns for a worthwhile life)] [21]. This approach has been effective in reducing anger, psychological distress, and social anxiety and improving interpersonal relationships among students [22, 23]. The internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is effective in reducing stress and depression while also enhancing the psychological well-being of students [24, 25]. By promoting psychological flexibility, this approach enables individuals to confront life's challenges more effectively. Midwifery students play a crucial role in maternal and newborn health, as well as in supporting childbearing. However, they often encounter issues that may jeopardize their mental health. Considering the limitations of existing studies and the presence of conflicting results, this research was designed to assess the impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on feeling of inferiority and academic engagement among midwifery students.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This study was a randomized controlled trial without blinding that commenced on 2023 November 21, following the receipt of the ethics approval from the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences. It was also registered on the Iranian Clinical Trials Center website.

Participants and sampling

This study was conducted at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences. The study population consisted of all undergraduate midwifery students at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences who were enrolled in the 2023-2024 academic year. Inclusion criteria included studying in the field of midwifery at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, full consent to participate in the study, and having physical and mental health (based on the participants' self-report form). Exclusion criteria for the study included failure to complete the post-intervention and follow-up questionnaires, submitting incomplete responses, missing more than two educational sessions, participating in concurrent other psychotherapy programs, unwillingness to continue participation, and the occurrence of unforeseen events. For sample size calculations, we used the formula for randomized clinical trials:

n = ((S12 + S22) × (Z2 (1-α⁄2) + Z2 (1-β))) ÷ (X1 – X2)2

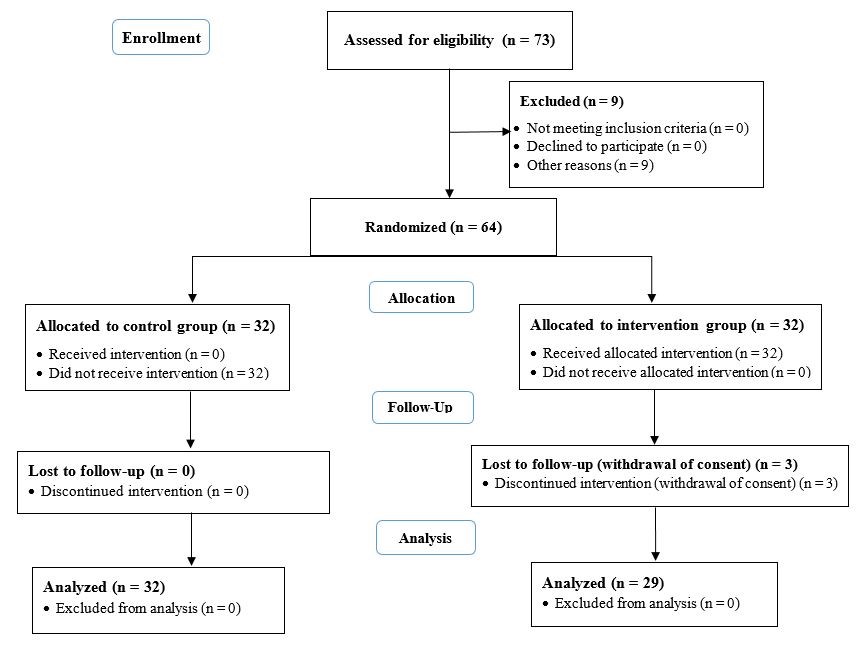

Based on the study by Fang and Ding [26], the estimated mean scores for total academic engagement in the control and intervention groups were 70.76 and 81.33, respectively, with standard deviations of 15.32 and 11.68. Considering a 95% confidence level and an 80% test power, the sample size was calculated to be 26 people in each group. With a 20% probability of attrition, 32 people in each group and 64 people were included in the study [26]. The participants in the study were 64 undergraduate midwifery students from Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, who were recruited through convenience sampling. Individuals were allocated to the intervention (A) and control (B) groups by randomly selecting 16 blocks of four from a set of six possible sequences: AABB, BBAA, ABAB, BABA, ABBA, or BAAB. Each of these blocks was assigned a number, and then 16 blocks were selected using a random number table. To conceal the allocation of participants to the two intervention and control groups, 64 envelopes were prepared before the work began. Each envelope was numbered from one to 64 (participant code). According to the list of blocks selected in the previous stage, apiece of paper with the word "intervention" or "control" written on it was placed inside each envelope. Each of the eligible individuals who entered the study was given a sealed envelope in numerical order. The content inside the envelope determined the participant's allocation to the intervention or control group. Thus, each of the 64 participants who entered the study was assigned to one of the two groups: intervention (32 participants) or control (32 participants). This study lacked post-allocation concealment. After the intervention began, three participants in the intervention group dropped out of the study due to unwillingness to continue cooperation, and ultimately, data from 61 participants were reviewed and statistically analyzed (Figure 1).

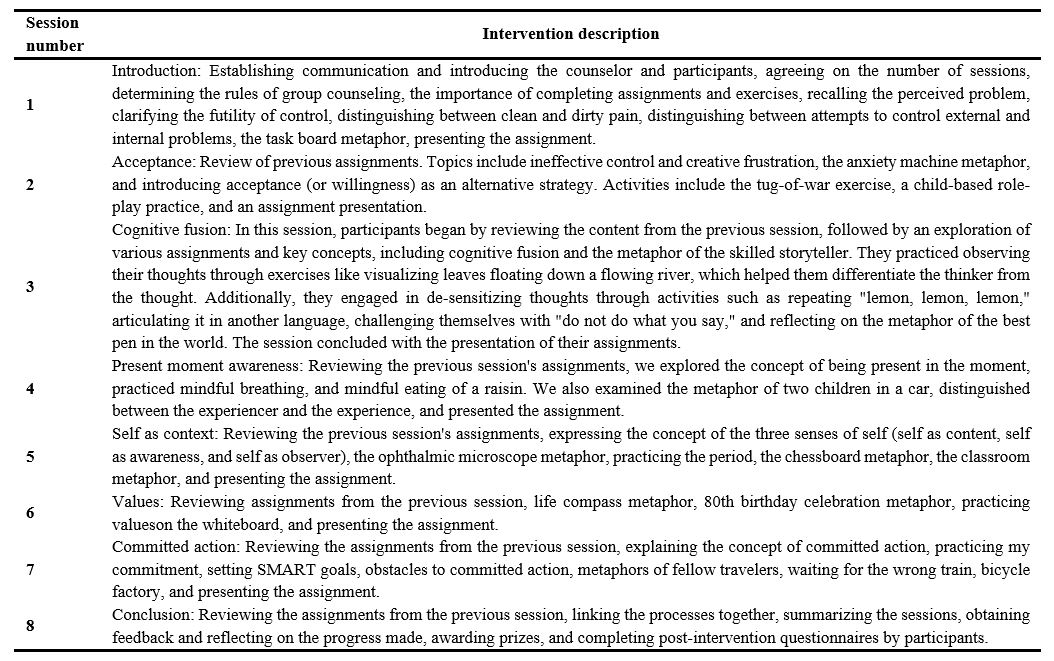

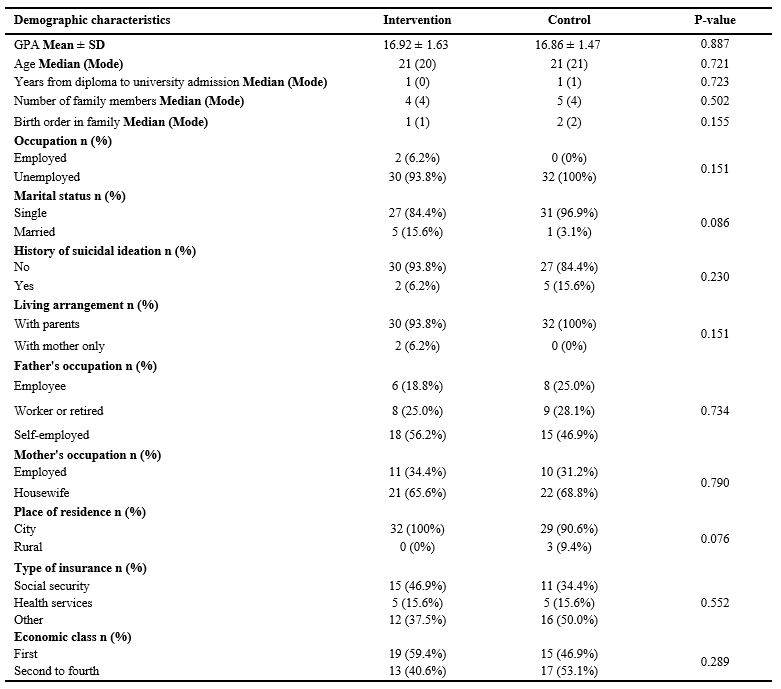

Table 1. Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

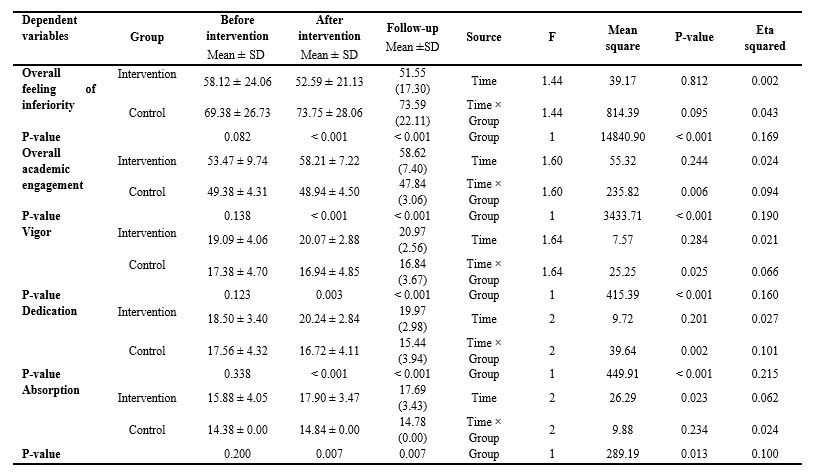

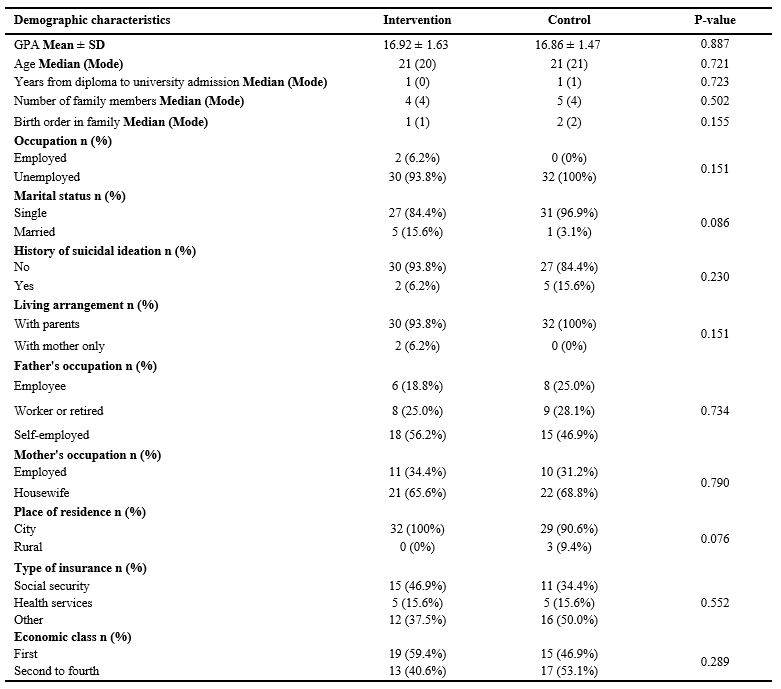

Table 2. Comparison of demographic characteristics between intervention and control groups

Note: Independent t-test was used for comparing quantitative demographic variables with mean and standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U test was used for quantitative variables with median and mode. Chi-square test was employed for qualitative variables.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P-value, probability-value; n, number of participants.

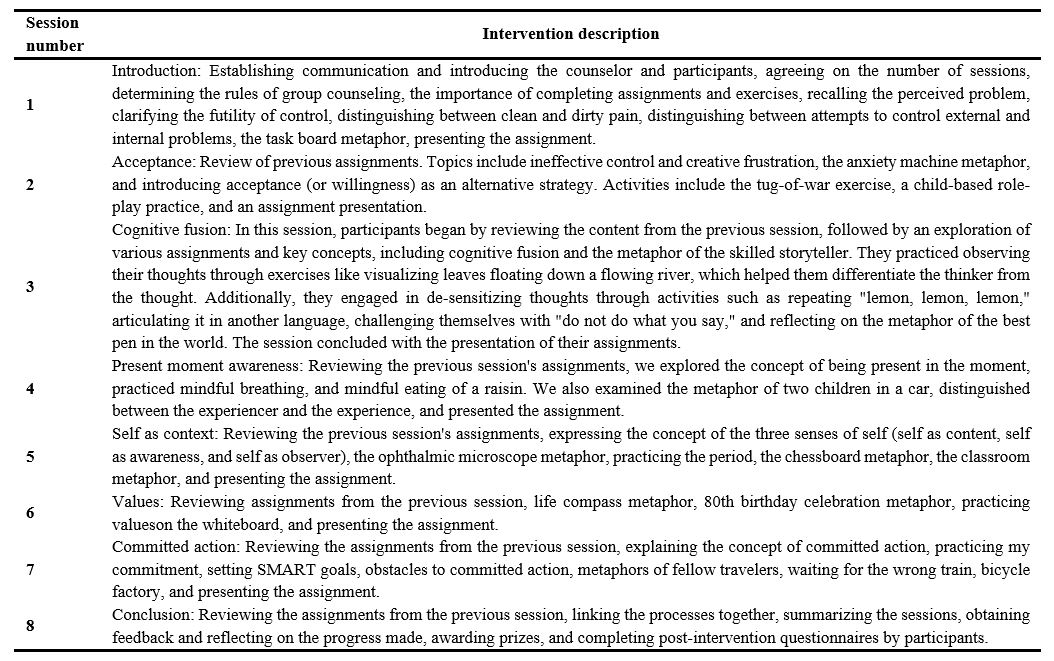

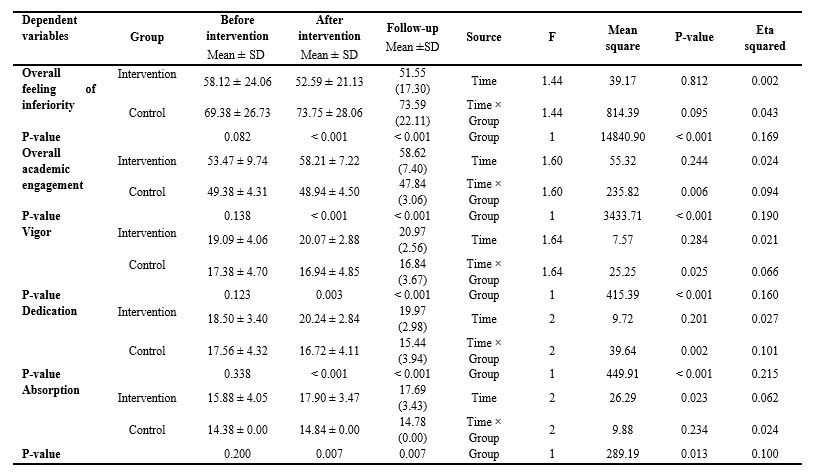

Table 3. Comparison of dependent variables across three study phases based on repeated measures ANOVA results

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy was effective on general feeling of inferiority, general academic engagement, and its subgroups, including vigor, dedication, and absorption.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy reduced feeling of inferiority in the intervention group compared to the control group. In line with this study, Sundah [31] demonstrated that group counseling based on Adler's theory was effective in overcoming inferiority, increasing self-confidence, and enhancing academic achievement among students. Additionally, Li et al. demonstrated that the group counseling program designed to manage inferiority not only reduced negative attitudes toward it but also increased positive attitudes toward it [6]. What they have in common with the present study is the use of the group counseling method. Group dynamics encourage individuals to engage in group activities and support one another in improving their abilities, regardless of their differences. Studies by Aghili and Ramrodi [32] and Varposhti Ghameshloo [33] demonstrated that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy effectively reduced feeling of inferiority in individuals with physical and motor disabilities, as well as in mothers of children with severe intellectual disabilities. A key similarity between these studies and the present research is the use of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for counseling and, in some instances, the application of the same tool, specifically the one developed by Yao et al. Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire. Inconsistent with this study, Shaghaqi et al. [11] examined a sample of 40 students using the same methodology as the authors of this study. The Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire (12 items) showed that social skills training increased hope, while this training did not affect their feeling of inferiority. Different results from some studies may be due to differences in the type of intervention, sample size, or measurement tools. It is suggested that the interventions and tools used be selected based on the characteristics of the research population.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy increased academic engagement in the intervention group compared to the control group. In alignment with this study, research by Fang and Ding [26] and Grégoire et al. [34] has indicated that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy enhances psychological resilience, well-being, and academic engagement while also reducing symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression among students and adolescents. While earlier studies focused on school students populations, the current study specifically examines university students population. What they have in common with this study is the type of intervention used. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, by increasing psychological resilience, enables individuals to approach life's problems more effectively and realistically. In contrast to the findings of this study, Dunnigan [18] found no significant relationship between teaching acceptance and commitment-based strategies and the improvement of students' academic engagement during the coronavirus pandemic. The different results from the present study are likely because the participants enrolled in that study did not have baseline levels that indicated the need for intervention. In addition, it is hypothesized that stressors related to the coronavirus pandemic may have outweighed the effect of acceptance and commitment-based strategy training.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy significantly increased the components of academic engagement—vigor, dedication, and absorption—in the intervention group compared to the control group. Supporting this study, research by Rajabian et al. [35] and Sadeghi et al. [36] demonstrated that blended learning and positive thinking skills effectively improved self-concept, academic optimism, academic engagement, and its components (vigor, dedication, and absorption) among students. A commonality between the current study and previous research is the use of the same instrument, the Schaufeli Academic Engagement Questionnaire, and a nearly similar sample size. Additionally, Rahmani [37] examined 30 students and found that group training using an acceptance and commitment approach was effective in promoting academic flourishing, willingness to continue education, and academic engagement along with its components, including vigor and dedication. However, unlike the present study, Rahmani's findings indicated that this approach was not effective in enhancing the component of absorption. The differing sample size and population—school students versus university students—may account for this discrepancy.

One limitation of the present study is the short follow-up period, which was constrained by the duration of the student's academic semester. A more extended follow-up period should be considered in future research. Additionally, the present study did not incorporate a tool to assess which of the six counseling processes based on acceptance and commitment had the most significant impact on improving students' feeling of inferiority and

academic engagement. It is recommended that such tools be utilized in future studies to assess the performance of these processes more accurately. The strengths of this study include the fact that the educational sessions were held in person. Face-to-face education, considering nonverbal communication, can have a more effective impact than holding online sessions. Furthermore, while most related studies have focused on the school students community, the present study specifically examined the aforementioned variables within the university students population. Another strength of this study is the comprehensiveness of the review of previous studies, which has attempted to examine most of the studies related to the subject.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy are effective in improving the feeling of inferiority and academic engagement of midwifery students. Therefore, it is recommended that educational policymakers make the necessary plans to hold Acceptance and Commitment Therapy training workshops for midwifery professors and students. This approach will first enhance students' personal lives and subsequently help them build better relationships with professors, staff, and clients in healthcare centers. By increasing students' flexibility, they will be better equipped to tackle academic and clinical challenges more effectively. The implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy by midwifery professors, who maintain continuous and effective communication with their students, can play a crucial role in preventing feeling of inferiority and lack of academic engagement, thereby reducing related complications. Ultimately, this can improve the quality of life for midwifery students by fostering behaviors that are more efficient.

Ethical considerations

This article is part of the corresponding author's master's thesis, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vice-Chancellor of Research, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, under the ID number IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.197 and registered on the website of the Iranian Clinical Trials Registry under the code IRCT20160608028352N12. All participants were informed about the study's objectives, the confidentiality of their information, and the voluntary nature of their participation. All students also completed a written informed consent form.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

No artificial intelligence programs were used to write this article.

Acknowledgment

We hereby sincerely thank and appreciate the support of the Honorable Vice Chancellor and Research Council of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences and the cooperation of the officials of the School of Nursing and Midwifery and the students participating in the study.

Conflict of interest statement

The researchers declare that they have no conflict of interest in any stage of the study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design of the idea: RK and ZN; design of the intervention protocol: RK and ZN; data collection: ZN; data analysis and interpretation of results: RK and ZN; preparation of draft and editing: ZN; final approval, control, and supervision: RK, EA, and EM; responsibility for accountability: ZN.

Funding

Zanjan University of Medical Sciences has financialy supported this study.

Data availability statement

The data for this study are available in full in the article. For further information, please contact the corresponding author.

Background & Objective: Midwifery students are more at risk of psychological harm than other students due to their specific professional characteristics. Feeling of inferiority and lack of academic engagement can lead to reduced academic performance and increased psychological problems. This study aimed to investigate the impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on feeling of inferiority and academic engagement among midwifery students.

Materials & Methods: This randomized controlled trial involved 2023-2024. Sixty-four undergraduate midwifery students were selected using a convenience sampling method. After obtaining written informed consent, the students were randomly assigned to two groups: one intervention group and one control group, each consisting of 32 participants. The intervention consisted of eight 60-minute sessions (once a week) of group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. The control group did not receive any intervention. The research tools included a demographic checklist, Yao et al. Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire and Schaufeli et al. Academic Engagement Questionnaire. The questionnaires were completed by the participants in three stages: before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and one month after the intervention. Relevant statistical tests, using SPSS version 16, were employed to analyze the data.

Results: The results showed that after the intervention, the mean scores of feeling of inferiority and academic engagement between the intervention and control groups were significantly different (p < 0.05). In the intervention group, the mean of overall feeling of inferiority before the intervention was 58.12 ± 24.06; after the intervention, it decreased to 52.59 ± 21.13 and at follow-up, it further declined to 51.55 ± 17.30. In terms of overall academic engagement, the mean scores before the intervention were 53.47 ± 9.74, which changed to 58.21 ± 7.22 after the intervention and increased slightly to 58.62 ± 7.40 at follow-up. For the control group, the mean scores for general feeling of inferiority were as follows: before the intervention, it was 69.38 ± 26.73; after the intervention, it was 73.75 ± 28.06; and at follow-up, it was 73.59 ± 22.11. Regarding general academic engagement, the scores were 49.38 ± 4.31 before the intervention, 48.94 ± 4.50 after the intervention, and 47.84 ± 3.06 at follow-up.

Conclusion: Based on the study's findings, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is recommended to enhance students' feeling of inferiority and academic engagement. It seems that teaching this counseling method to students in the form of a workshop will help them deal with academic and clinical problems more efficiently.

Introduction

Students are the spiritual backbone of society and the future architects of our nation. The importance of the field of midwifery is evident through maternal and neonatal outcomes, which serve as indicators of health and quality of life among countries [1]. Midwifery students, as the future midwives of the country, play a vital role in promoting maternal and neonatal health, as well as encouraging childbearing. However, medical students often face a higher risk of psychological harm compared to their peers due to unique challenges. These challenges include the mental and emotional pressures of the hospital environment, difficulties in managing patients' issues, and uncertainty about their career futures [2]. Among paramedical students, the highest levels of stress are found in the midwifery group, particularly about unpleasant emotions, clinical experiences, humiliating situations, the educational environment, and interpersonal relationships [3] Feeling of inferiority often stem from a sense of weakness and helplessness, which can persist from childhood and be exacerbated by physical or mental challenges. This can lead to feelings of despair and failure [4]. Increased levels of negative feeling of inferiority in students are directly related to rumination, social anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation [5, 6]. This feeling also causes students to experience a decline in academic performance and achievement, ultimately leading to lower psychological well-being [7-9]. Therefore, approaches such as group counseling based on inferiority management, group psychodrama, and social skills training have been used to reduce students' feeling of inferiority [10-12]. Although feeling of inferiority hurt academic achievement, support from parents, teachers, and peers indirectly affects academic achievement through perceived academic engagement [13]. Schaufeli et al. define academic engagement as a positive, satisfying, and academically relevant state of mind characterized by three dimensions: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Rather than being a momentary, specific state, academic engagement refers to a more enduring and pervasive cognitive-emotional state that is not focused on any specific object, event, person, or behavior [14]. Academic engagement is positively correlated with psychological capital and academic success and negatively correlated with academic burnout [15, 16]. Additionally, students that are more anxious tend to experience poorer sleep quality, which in turn negatively affects their academic engagement [17]. Researchers have reported conflicting results on the effects of mindfulness interventions and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on academic engagement in students [18, 19]. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy introduced by Hayes et al. in 1982. This approach is based on mindfulness, and increasing psychological flexibility is considered one of its primary goals [20]. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy includes six processes: 1- acceptance (being open to unwanted thoughts and feelings as they are), 2- cognitive fusion (withdrawing from unhelpful thoughts and feelings to reduce their dominance over behaviors), 3- present moment awareness (maintaining a voluntary and flexible connection with the present), 4- self as a context (flexible self-concept and perspective-taking), 5- values (clarifying personal values), and 6- committed action (creating behavioral patterns for a worthwhile life)] [21]. This approach has been effective in reducing anger, psychological distress, and social anxiety and improving interpersonal relationships among students [22, 23]. The internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is effective in reducing stress and depression while also enhancing the psychological well-being of students [24, 25]. By promoting psychological flexibility, this approach enables individuals to confront life's challenges more effectively. Midwifery students play a crucial role in maternal and newborn health, as well as in supporting childbearing. However, they often encounter issues that may jeopardize their mental health. Considering the limitations of existing studies and the presence of conflicting results, this research was designed to assess the impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on feeling of inferiority and academic engagement among midwifery students.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This study was a randomized controlled trial without blinding that commenced on 2023 November 21, following the receipt of the ethics approval from the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences. It was also registered on the Iranian Clinical Trials Center website.

Participants and sampling

This study was conducted at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences. The study population consisted of all undergraduate midwifery students at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences who were enrolled in the 2023-2024 academic year. Inclusion criteria included studying in the field of midwifery at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, full consent to participate in the study, and having physical and mental health (based on the participants' self-report form). Exclusion criteria for the study included failure to complete the post-intervention and follow-up questionnaires, submitting incomplete responses, missing more than two educational sessions, participating in concurrent other psychotherapy programs, unwillingness to continue participation, and the occurrence of unforeseen events. For sample size calculations, we used the formula for randomized clinical trials:

n = ((S12 + S22) × (Z2 (1-α⁄2) + Z2 (1-β))) ÷ (X1 – X2)2

Based on the study by Fang and Ding [26], the estimated mean scores for total academic engagement in the control and intervention groups were 70.76 and 81.33, respectively, with standard deviations of 15.32 and 11.68. Considering a 95% confidence level and an 80% test power, the sample size was calculated to be 26 people in each group. With a 20% probability of attrition, 32 people in each group and 64 people were included in the study [26]. The participants in the study were 64 undergraduate midwifery students from Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, who were recruited through convenience sampling. Individuals were allocated to the intervention (A) and control (B) groups by randomly selecting 16 blocks of four from a set of six possible sequences: AABB, BBAA, ABAB, BABA, ABBA, or BAAB. Each of these blocks was assigned a number, and then 16 blocks were selected using a random number table. To conceal the allocation of participants to the two intervention and control groups, 64 envelopes were prepared before the work began. Each envelope was numbered from one to 64 (participant code). According to the list of blocks selected in the previous stage, apiece of paper with the word "intervention" or "control" written on it was placed inside each envelope. Each of the eligible individuals who entered the study was given a sealed envelope in numerical order. The content inside the envelope determined the participant's allocation to the intervention or control group. Thus, each of the 64 participants who entered the study was assigned to one of the two groups: intervention (32 participants) or control (32 participants). This study lacked post-allocation concealment. After the intervention began, three participants in the intervention group dropped out of the study due to unwillingness to continue cooperation, and ultimately, data from 61 participants were reviewed and statistically analyzed (Figure 1).

Interventions

Eight 60-minute sessions (once a week) of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy were held for the intervention group in a group and in person (Table 1). To properly implement the intervention, the researcher used the guidance of the psychologists in the research team and

obtained a certificate of participation in the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy training workshop. The control group did not receive any intervention; however, it was explained to them that they could access the educational materials after the study concluded if they wished.

Eight 60-minute sessions (once a week) of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy were held for the intervention group in a group and in person (Table 1). To properly implement the intervention, the researcher used the guidance of the psychologists in the research team and

obtained a certificate of participation in the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy training workshop. The control group did not receive any intervention; however, it was explained to them that they could access the educational materials after the study concluded if they wished.

Table 1. Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Tools/Instruments

The instruments of this study included the demographic checklist, Yao et al. [28] Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire, and Schaufeli et al. [14] Academic Engagement Questionnaire.

The demographic checklist was used to collect information on personal, educational, family, and economic backgrounds. Scores from housing, infrastructure, and vehicle ownership questions were summed to calculate economic class [27]. Yao et al.

Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire (1997): This questionnaire is a self-report instrument comprising 34 items, including negative thoughts.

Seventeen of its items measure the individual's assessment of his or her feeling of inferiority, and 17 of its items measure feeling of inferiority related to the judgments of others (no reverse-scoring questions).

The content includes 15 items related to negative events, such as feelings of weakness, fatigue, mistakes, and criticism. It also features 15 items associated with positive events, such as feelings of worth, success, and praise. Additionally, four items reflect unconditional principles. This scale is graded on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all (1) to completely (5), and the total score of the scale ranges from 34 to 170. Higher scores than the mean indicate greater feeling of inferiority. The inferiority feeling scale exhibits a significant direct correlation with the Beck Depression Inventory (r = 0.61, p = 0.001), indicating the validity of this scale. Its reliability was also confirmed after five months through retesting (r = 0.84, p < 0.001), and the internal consistency of its items was established using Cronbach's

alpha coefficient of α = 0.95 [28]. Yousefi et al conducted the translation and psychometric evaluation of this instrument in Iran. They reported a correlation of the scale scores with the Beck Depression Inventory of r = 0.55, p < 0.001.

The reliability of the inferiority feeling scale was assessed, yielding a test-retest coefficient of r = 0.76 and a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of α = 0.89. These results indicate that the questionnaire possesses appropriate validity and reliability for use in Iran [29]. Schaufeli et al. [14] Academic Engagement Questionnaire: This questionnaire consists of 17 items and has three dimensions: vigor (items 1-6), dedication (items 7-11), and absorption (items 12-17). This scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from never (1) to always (5), and the total score range of the scale is between 17 and 85 (no questions with reverse scoring). Higher scores than the average indicate higher academic engagement. Experts and psychology professors have examined the content validity of the scale.

Additionally, the overall reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which was 0.73. The internal consistency of the scale for the dimensions of vigor, dedication, and absorption was reported to be 0.78, 0.91, and 0.73, respectively. In Iran, Qadmpour et al. translated and psychometrically evaluated the instrument with the assistance of five psychology professors, confirming its face and content validity.

To assess reliability, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the dimensions of vigor, dedication, absorption, and the total scale were found to be 0.94, 0.92, 0.79, and 0.88, respectively [30].

Data collection methods

After obtaining written informed consent and explaining the study's objectives, the primary data from participants were collected through a demographic checklist, Yao et al.'s Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire, and Schaufeli's Academic Engagement Questionnaire.

This process was conducted in a self-reported and face-to-face manner. Immediately and one month after the sessions, the participants in both the intervention and control groups completed the questionnaires again.

The corresponding author also provided his contact information to answer any questions from the participants.

Data analysis

After data collection, SPSS version 16 was used for data analysis. In descriptive analysis, the mean and standard deviation were reported for quantitative variables, and frequency and percentage were reported for qualitative variables. Independent t-tests, repeated measures tests, and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to calculate inferential statistics. The significance level in all tests was considered less than 0.05.

Results

The instruments of this study included the demographic checklist, Yao et al. [28] Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire, and Schaufeli et al. [14] Academic Engagement Questionnaire.

The demographic checklist was used to collect information on personal, educational, family, and economic backgrounds. Scores from housing, infrastructure, and vehicle ownership questions were summed to calculate economic class [27]. Yao et al.

Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire (1997): This questionnaire is a self-report instrument comprising 34 items, including negative thoughts.

Seventeen of its items measure the individual's assessment of his or her feeling of inferiority, and 17 of its items measure feeling of inferiority related to the judgments of others (no reverse-scoring questions).

The content includes 15 items related to negative events, such as feelings of weakness, fatigue, mistakes, and criticism. It also features 15 items associated with positive events, such as feelings of worth, success, and praise. Additionally, four items reflect unconditional principles. This scale is graded on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all (1) to completely (5), and the total score of the scale ranges from 34 to 170. Higher scores than the mean indicate greater feeling of inferiority. The inferiority feeling scale exhibits a significant direct correlation with the Beck Depression Inventory (r = 0.61, p = 0.001), indicating the validity of this scale. Its reliability was also confirmed after five months through retesting (r = 0.84, p < 0.001), and the internal consistency of its items was established using Cronbach's

alpha coefficient of α = 0.95 [28]. Yousefi et al conducted the translation and psychometric evaluation of this instrument in Iran. They reported a correlation of the scale scores with the Beck Depression Inventory of r = 0.55, p < 0.001.

The reliability of the inferiority feeling scale was assessed, yielding a test-retest coefficient of r = 0.76 and a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of α = 0.89. These results indicate that the questionnaire possesses appropriate validity and reliability for use in Iran [29]. Schaufeli et al. [14] Academic Engagement Questionnaire: This questionnaire consists of 17 items and has three dimensions: vigor (items 1-6), dedication (items 7-11), and absorption (items 12-17). This scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from never (1) to always (5), and the total score range of the scale is between 17 and 85 (no questions with reverse scoring). Higher scores than the average indicate higher academic engagement. Experts and psychology professors have examined the content validity of the scale.

Additionally, the overall reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which was 0.73. The internal consistency of the scale for the dimensions of vigor, dedication, and absorption was reported to be 0.78, 0.91, and 0.73, respectively. In Iran, Qadmpour et al. translated and psychometrically evaluated the instrument with the assistance of five psychology professors, confirming its face and content validity.

To assess reliability, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the dimensions of vigor, dedication, absorption, and the total scale were found to be 0.94, 0.92, 0.79, and 0.88, respectively [30].

Data collection methods

After obtaining written informed consent and explaining the study's objectives, the primary data from participants were collected through a demographic checklist, Yao et al.'s Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire, and Schaufeli's Academic Engagement Questionnaire.

This process was conducted in a self-reported and face-to-face manner. Immediately and one month after the sessions, the participants in both the intervention and control groups completed the questionnaires again.

The corresponding author also provided his contact information to answer any questions from the participants.

Data analysis

After data collection, SPSS version 16 was used for data analysis. In descriptive analysis, the mean and standard deviation were reported for quantitative variables, and frequency and percentage were reported for qualitative variables. Independent t-tests, repeated measures tests, and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to calculate inferential statistics. The significance level in all tests was considered less than 0.05.

Results

The mean Grade Point Average (GPA) of the participants in the intervention group was 16.92 ± 1.63, while the control group had a mean of 16.86 ± 1.47. The median age of the students in both groups was 21 years. The mean of the demographic variables of the two intervention and control groups did not differ significantly (Table 2). In the intervention group, the mean (standard deviation) of the general feeling of inferiority before the intervention was 58.12 ± 24.06, and in the control group, it was 69.38 ± 26.73. Additionally, in the intervention group, the general academic engagement prior to the intervention was 53.47 ± 9.74, while in the control group, it was 49.38 ± 4.31. The mean scores for general feeling of inferiority, overall academic engagement, and its subgroups—including vigor, dedication, and absorption—did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups at the pre-intervention stage, indicating that the two groups were homogeneous in these behaviors. In the intervention group, the mean (standard deviation) for the overall feeling of inferiority after the intervention was 52.59 ± 21.13, with a follow-up score of 51.55 ± 17.30. In contrast, the control group had scores of 73.75 ± 28.06 after the intervention and 73.59 ± 22.11 at follow-up. The mean score for the overall feeling of inferiority in the intervention group decreased compared to the control group, and this trend remained stable during the follow-up period. Regarding overall academic engagement, the intervention group had mean (standard deviation) scores of 58.21 ± 7.22 after the intervention and 58.62 ± 7.40 at follow-up. In contrast, the control group recorded scores of 48.94 ± 4.50 after the intervention and 47.84 ± 3.06 at follow-up. The mean score of overall academic engagement in the intervention group increased compared to the control group after the intervention, and this trend remained stable during the follow-up period. The results of the repeated measures test indicated that the changes in general feeling of inferiority and absorption between the intervention and control groups were significant after adjusting for baseline variables. Additionally, the changes in general academic engagement, vigor, and dedication were found to be

significant due to the interaction between group and time. The Bonferroni post hoc test was used to explain the direction of the relationship. The results revealed that in the intervention group, the vigor score changed significantly from pre-intervention to post-intervention and follow-up, and the general academic engagement

score also showed significant changes over the same period (p < 0.05). In the control group, the dedication score decreased significantly from pre-intervention to post-intervention and follow-up; however, there were no significant changes in the scores of the other variables mentioned (Table 3).

significant due to the interaction between group and time. The Bonferroni post hoc test was used to explain the direction of the relationship. The results revealed that in the intervention group, the vigor score changed significantly from pre-intervention to post-intervention and follow-up, and the general academic engagement

score also showed significant changes over the same period (p < 0.05). In the control group, the dedication score decreased significantly from pre-intervention to post-intervention and follow-up; however, there were no significant changes in the scores of the other variables mentioned (Table 3).

Table 2. Comparison of demographic characteristics between intervention and control groups

Note: Independent t-test was used for comparing quantitative demographic variables with mean and standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U test was used for quantitative variables with median and mode. Chi-square test was employed for qualitative variables.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P-value, probability-value; n, number of participants.

Table 3. Comparison of dependent variables across three study phases based on repeated measures ANOVA results

Note: Independent t-test was used to compare group differences at each time point. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate changes over time and interaction effects.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P-value, probability-value; F, analysis of variance test; Eta squared, effect size; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P-value, probability-value; F, analysis of variance test; Eta squared, effect size; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy was effective on general feeling of inferiority, general academic engagement, and its subgroups, including vigor, dedication, and absorption.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy reduced feeling of inferiority in the intervention group compared to the control group. In line with this study, Sundah [31] demonstrated that group counseling based on Adler's theory was effective in overcoming inferiority, increasing self-confidence, and enhancing academic achievement among students. Additionally, Li et al. demonstrated that the group counseling program designed to manage inferiority not only reduced negative attitudes toward it but also increased positive attitudes toward it [6]. What they have in common with the present study is the use of the group counseling method. Group dynamics encourage individuals to engage in group activities and support one another in improving their abilities, regardless of their differences. Studies by Aghili and Ramrodi [32] and Varposhti Ghameshloo [33] demonstrated that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy effectively reduced feeling of inferiority in individuals with physical and motor disabilities, as well as in mothers of children with severe intellectual disabilities. A key similarity between these studies and the present research is the use of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for counseling and, in some instances, the application of the same tool, specifically the one developed by Yao et al. Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire. Inconsistent with this study, Shaghaqi et al. [11] examined a sample of 40 students using the same methodology as the authors of this study. The Inferiority Feeling Questionnaire (12 items) showed that social skills training increased hope, while this training did not affect their feeling of inferiority. Different results from some studies may be due to differences in the type of intervention, sample size, or measurement tools. It is suggested that the interventions and tools used be selected based on the characteristics of the research population.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy increased academic engagement in the intervention group compared to the control group. In alignment with this study, research by Fang and Ding [26] and Grégoire et al. [34] has indicated that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy enhances psychological resilience, well-being, and academic engagement while also reducing symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression among students and adolescents. While earlier studies focused on school students populations, the current study specifically examines university students population. What they have in common with this study is the type of intervention used. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, by increasing psychological resilience, enables individuals to approach life's problems more effectively and realistically. In contrast to the findings of this study, Dunnigan [18] found no significant relationship between teaching acceptance and commitment-based strategies and the improvement of students' academic engagement during the coronavirus pandemic. The different results from the present study are likely because the participants enrolled in that study did not have baseline levels that indicated the need for intervention. In addition, it is hypothesized that stressors related to the coronavirus pandemic may have outweighed the effect of acceptance and commitment-based strategy training.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy significantly increased the components of academic engagement—vigor, dedication, and absorption—in the intervention group compared to the control group. Supporting this study, research by Rajabian et al. [35] and Sadeghi et al. [36] demonstrated that blended learning and positive thinking skills effectively improved self-concept, academic optimism, academic engagement, and its components (vigor, dedication, and absorption) among students. A commonality between the current study and previous research is the use of the same instrument, the Schaufeli Academic Engagement Questionnaire, and a nearly similar sample size. Additionally, Rahmani [37] examined 30 students and found that group training using an acceptance and commitment approach was effective in promoting academic flourishing, willingness to continue education, and academic engagement along with its components, including vigor and dedication. However, unlike the present study, Rahmani's findings indicated that this approach was not effective in enhancing the component of absorption. The differing sample size and population—school students versus university students—may account for this discrepancy.

One limitation of the present study is the short follow-up period, which was constrained by the duration of the student's academic semester. A more extended follow-up period should be considered in future research. Additionally, the present study did not incorporate a tool to assess which of the six counseling processes based on acceptance and commitment had the most significant impact on improving students' feeling of inferiority and

academic engagement. It is recommended that such tools be utilized in future studies to assess the performance of these processes more accurately. The strengths of this study include the fact that the educational sessions were held in person. Face-to-face education, considering nonverbal communication, can have a more effective impact than holding online sessions. Furthermore, while most related studies have focused on the school students community, the present study specifically examined the aforementioned variables within the university students population. Another strength of this study is the comprehensiveness of the review of previous studies, which has attempted to examine most of the studies related to the subject.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy are effective in improving the feeling of inferiority and academic engagement of midwifery students. Therefore, it is recommended that educational policymakers make the necessary plans to hold Acceptance and Commitment Therapy training workshops for midwifery professors and students. This approach will first enhance students' personal lives and subsequently help them build better relationships with professors, staff, and clients in healthcare centers. By increasing students' flexibility, they will be better equipped to tackle academic and clinical challenges more effectively. The implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy by midwifery professors, who maintain continuous and effective communication with their students, can play a crucial role in preventing feeling of inferiority and lack of academic engagement, thereby reducing related complications. Ultimately, this can improve the quality of life for midwifery students by fostering behaviors that are more efficient.

Ethical considerations

This article is part of the corresponding author's master's thesis, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vice-Chancellor of Research, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, under the ID number IR.ZUMS.REC.1402.197 and registered on the website of the Iranian Clinical Trials Registry under the code IRCT20160608028352N12. All participants were informed about the study's objectives, the confidentiality of their information, and the voluntary nature of their participation. All students also completed a written informed consent form.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

No artificial intelligence programs were used to write this article.

Acknowledgment

We hereby sincerely thank and appreciate the support of the Honorable Vice Chancellor and Research Council of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences and the cooperation of the officials of the School of Nursing and Midwifery and the students participating in the study.

Conflict of interest statement

The researchers declare that they have no conflict of interest in any stage of the study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design of the idea: RK and ZN; design of the intervention protocol: RK and ZN; data collection: ZN; data analysis and interpretation of results: RK and ZN; preparation of draft and editing: ZN; final approval, control, and supervision: RK, EA, and EM; responsibility for accountability: ZN.

Funding

Zanjan University of Medical Sciences has financialy supported this study.

Data availability statement

The data for this study are available in full in the article. For further information, please contact the corresponding author.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2025/02/5 | Accepted: 2025/07/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/02/5 | Accepted: 2025/07/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

References

1. Cunningham FG, Leveno K, Dashe J, Hoffman B, Spong C, Casey B. Williams obstetrics. 26th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2022. p. 1-20.

2. Shahabinejad M, Sadeghi T, Salem Z. Assessment of the mental health of nursing students. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;4(2):29-37. [DOI:10.21859/ijpn-04024]

3. Poorheidari M, Delvarian-Zadeh M, Yahyaee S, Montazeri AS. Study of the stressful experiences of midwifery students during clinical education in the labor room. Res Med Educ. 2018;9(4):58-66. [DOI:10.29252/rme.9.4.66]

4. Adler A, Wolfe WB. The feeling of inferiority and the striving for recognition. Proc R Soc Med. 1927;20(12):1881-6. [DOI:10.1177/003591572702001246] [PMID] []

5. Cimsir E. The roles of dispositional rumination, inferiority feelings and gender in interpersonal rumination experiences of college students. J Gen Psychol. 2019;146(3):217-33. [DOI:10.1080/00221309.2018.1553844] [PMID]

6. Li J, Jia S, Wang L, Zhang M, Chen S. Relationships among inferiority feelings, fear of negative evaluation, and social anxiety in Chinese junior high school students. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1-9. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015477] [PMID] []

7. Dhara R, Barman P. Inferiority complex, adjustment problem and academic performance of differently-abled students in the state of West Bengal. Humanit Soc Sci Rev. 2020;8(3):1383-94. [DOI:10.18510/hssr.2020.83139]

8. Kabir SS, Rashid UK. Interpersonal values, inferiority complex, and psychological well-being of teenage students. Jagannath Univ J Life Earth Sci. 2017;3(1):127-34.

9. Venkataraman S, Manivannan S. Inferiority complex of high school students in relation to their academic achievement. Int J Commun Media Stud. 2018;8(5):55-62. [DOI:10.24247/ijcmsdec20187]

10. Lee MH, Park YJ, Jang HC. Evaluating the effects of inferiority management using a group counseling program for university students in health science. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2019;13(4):557-63.

11. Shaghaqi F, Aghayousofi A, Georgian R. The effectiveness of social skills training on the level of hope and feeling of inferiority in students of the university of economic sciences. New Ideas Psychol Q. 2022;12(14):1-8.

12. Tümlü GÜ, Şimşek BK. The effects of psychodrama groups on feeling of inferiority, flourishing, and self-compassion in research assistants. Arts Psychother. 2021;73:1-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.aip.2021.101763]

13. Lei H, Cui Y, Zhou W. Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Soc Behav Personal. 2018;46(3):517-28. [DOI:10.2224/sbp.7054]

14. Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71-92. [DOI:10.1023/A:1015630930326]

15. Tomás JM, Gutiérrez M, Georgieva S, Hernández M. The effects of self-efficacy, hope, and engagement on the academic achievement of secondary education in the Dominican Republic. Psychol Sch. 2020;57(2):1-13. [DOI:10.1002/pits.22321]

16. Wang J, Bu L, Li Y, Song J, Li N. The mediating effect of academic engagement between psychological capital and academic burnout among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;1:102-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104938] [PMID] []

17. Ng HT, Zhang C-Q, Phipps D, Zhang R, Hamilton K. Effects of anxiety and sleep on academic engagement among university students. Aust Psychol. 2022;57(1):57-64. [DOI:10.1080/00050067.2021.1965854]

18. Dunnigan MR. Effects of teaching acceptance and commitment therapy-based strategies on improving academic engagement and participation for students in an applied behavior analysis master's program [dissertation]. East Lansing (MI): Michigan State University; 2021.

19. Ghasemi F, Emadian SO, Hassanzadeh R. Comparison of the effectiveness of mindfulness and acceptance and commitment education on academic motivation of female students during the COVID-19 epidemic. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2021;64(5):4131-44.

20. Hayes S, Strosahl K, Wilson K. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York (NY): The Guilford Press; 1999. p. 1-304.

21. Hayes SC, Pistorello J, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. Couns Psychol. 2012;40(7):976-1002. [DOI:10.1177/0011000012460836]

22. Repo S, Elovainio M, Pyörälä E, Iriarte-Lüttjohann M, Tuominen T, Härkönen T, et al. Comparison of two different mindfulness interventions among health care students in Finland: a randomised controlled trial. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2022;27(3):709-34. [DOI:10.1007/s10459-022-10116-8] [PMID] []

23. Toghiani Z, Ghasemi F, Samouei R. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment group therapy on social anxiety in female dormitory residents in Isfahan university of medical sciences. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8(41):1-5. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_111_18] [PMID] []

24. Ferrari M, Allan S, Arnold C, Eleftheriadis D, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gumley A, et al. Digital interventions for psychological well-being in university students: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(9):1-17. [DOI:10.2196/39686] [PMID] []

25. Räsänen P, Muotka J, Lappalainen R. Examining mediators of change in wellbeing, stress, and depression in a blended, Internet-based, ACT intervention for university students. Internet Interv. 2020;22:1-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.invent.2020.100343] [PMID] []

26. Fang S, Ding D. The efficacy of group-based acceptance and commitment therapy on psychological capital and school engagement: a pilot study among Chinese adolescents. J Context Behav Sci. 2020;16:134-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.04.005]

27. Rose D, Pevalin D. The national statistics socio-economic classification: unifying official and sociological approaches to the conceptualisation and measurement of social class in the United Kingdom. Soc Contemp. 2002;(45-46):75-106. [DOI:10.3917/soco.045.0075]

28. Yao S, Cottraux J, Martin R, et al. Inferiority, guilt and responsibility in OCD, social phobics and controls. Psychother Cogn Comport. 1997;3(2):304-18.

29. Yousefi R, Mazaheri MA, Adhamyan E. Inferiority feeling in social phobia and obsessive compulsive disorder patients. J Iran Psychol. 2008;5(17):63-8.

30. Qadmpour E, Ghasemi Pir Baluti M, Hasanvand B, Khalili Gashnigani Z. Psychometric characteristics of students' academic engagement scale. Q Educ Meas. 2017;8(29):167-84.

31. Sundah AJ. The impact of Adlerian group counseling on inferiority complex for academic success of public junior high school students. NeuroQuantology. 2022;20(18):884-91.

32. Aghili M, Ramrodi S. Effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on goal orientation and feeling of inferiority in individuals with physical-motor disabilities. Iran J Health Psychol. 2021;3(2):79-88.

33. Varposhti Ghameshloo A. Investigating the effectiveness of treatment based on admition and

34. commitment on worry and anxiety among exotic children's mother [dissertation]. Natanz: Payame Noor University; 2018.

35. Grégoire S, Lachance L, Bouffard T, Dionne F. The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to promote mental health and school engagement in university students: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2018;49(3):360-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2017.10.003] [PMID]

36. Rajabian M, Nazer Shandi M, Jangizehi H, Hosseini MA. The effect of blended education on students' self-concept and academic eagerness. Q J Educ Law Enforc Sci. 2022;9(35):150-83.

37. Sadeghi M, Abbasi M, Beiranvand Z. The effectiveness of training in positive thinking skills based on Quilliam's package on academic optimism and academic engagement of female students. Sch Educ Psychol. 2020;8(4):156-75.

38. Rahmani Z. The effect of group style ACT education on academic prosperity, desire to stay in education and academic motivation of high school students in Kermanshah [dissertation]. Esfahan: Payame Noor University; 2021.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |