Thu, Jan 29, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 4 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(4): 4-17 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IAU.TNB.REC.1398.009

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sedghi S, Sepehr F, Golestani A. Feasibility study and implementation of a questionnaire on the effectiveness of PhD curricula for knowledge management at medical universities in Iran. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (4) :4-17

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2396-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2396-en.html

1- Responsible Expert of the Library and Learning Center, Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Knowledge and Information Science, Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch, Tehran, Iran ,fereshteh.sepehr@yahoo.com

3- Department of Clinical Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Knowledge and Information Science, Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch, Tehran, Iran ,

3- Department of Clinical Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 635 kb]

(129 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (749 Views)

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Checking the quality and dynamics of higher education curricula and checking the effectiveness of courses provide valuable feedback for improving educational standards. This study aimed to design and carry out a questionnaire to investigate and compare the effectiveness of PhD. curricula in encouraging knowledge management, as perceived by graduates of medical sciences universities in Iran.

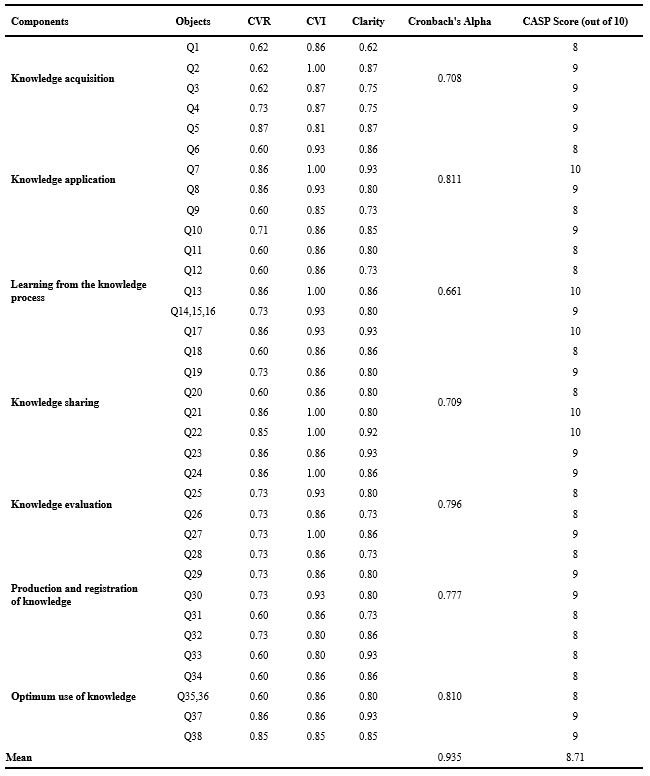

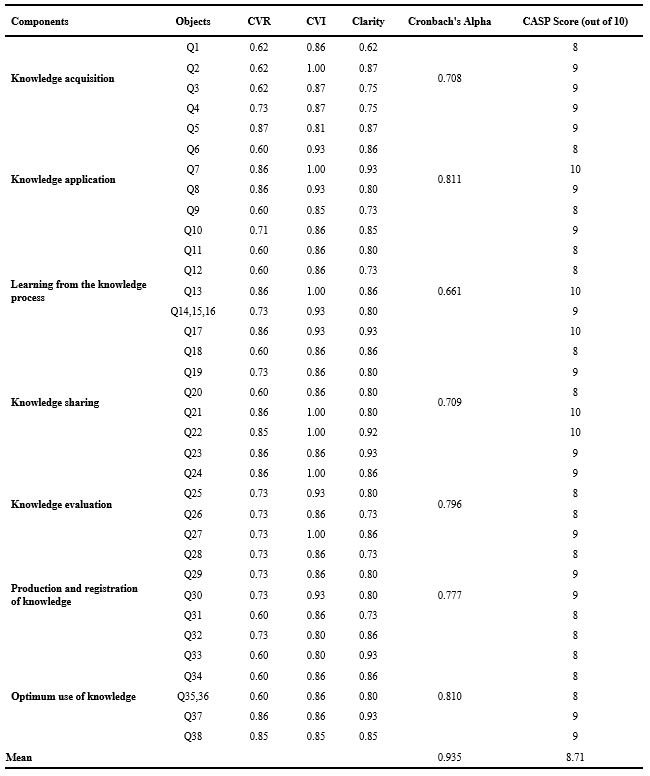

Materials & Methods: A questionnaire based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model was built, comprising 38 items. The Content Validity Index (CVI), Content Validity Ratio (CVR), and question clarity were checked. Internal consistency and reliability were confirmed using Cronbach's alpha and correlation coefficients. The finalized questionnaire was distributed to 221 PhD graduates in various fields of basic medical sciences from Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS). Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results: The questionnaire consisted of seven components, with a CVR of 0.72, CVI of 0.86, and clarity score of 0.82. The reliability of the questionnaire was strong, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.935, and a positive, significant correlation was seen among its components (p < 0.01). The mean scores for knowledge management in PhD courses, as rated by graduates, were similar across the three universities and above average. The highest mean scores were related to the "knowledge sharing" component (TUMS:3.2, IUMS:3.18, and SBUMS:3.14). The lowest mean scores were seen for the "learning from the knowledge process" component (IUMS:2.53, and SBUMS:2.65), and the "knowledge evaluation" component (TUMS:2.69).

Conclusion: The effectiveness of PhD curricula in encouraging knowledge management was rated above average by graduates of the investigated medical universities. However, the results highlight the need for greater stress on knowledge evaluation, knowledge elimination, and learning processes to improve the overall effectiveness of these programs.

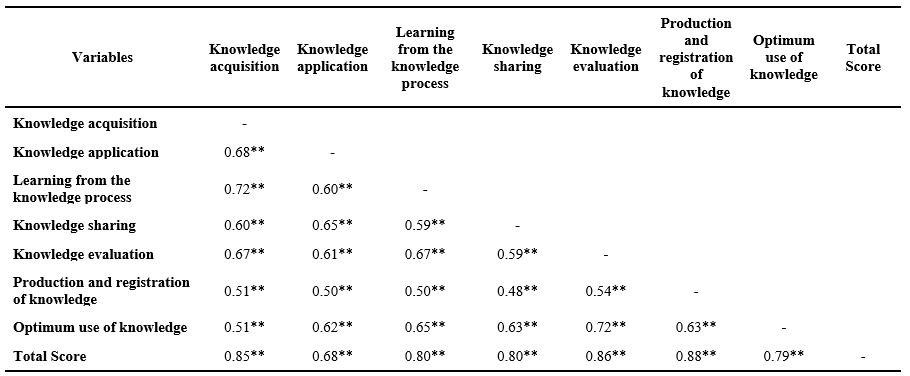

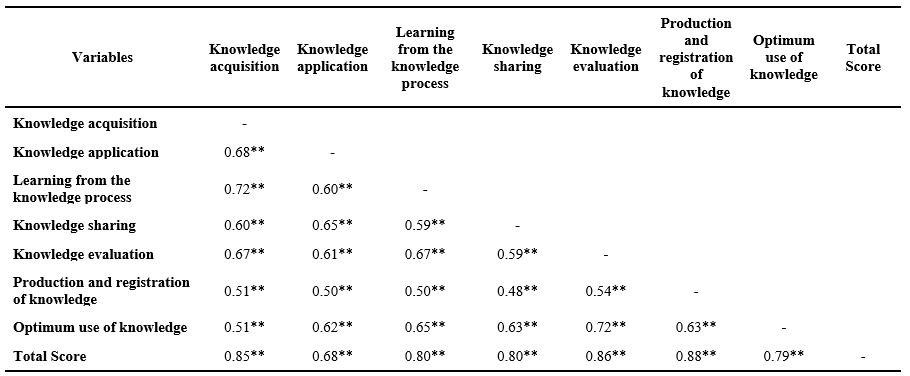

Table 2. Correlation matrix between knowledge management components and total score

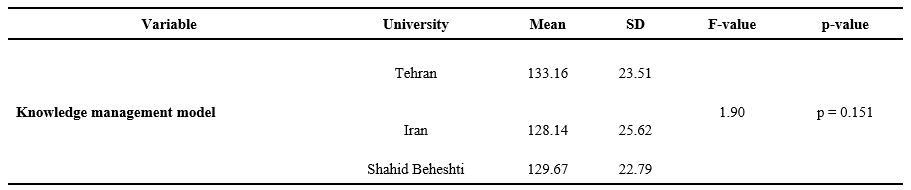

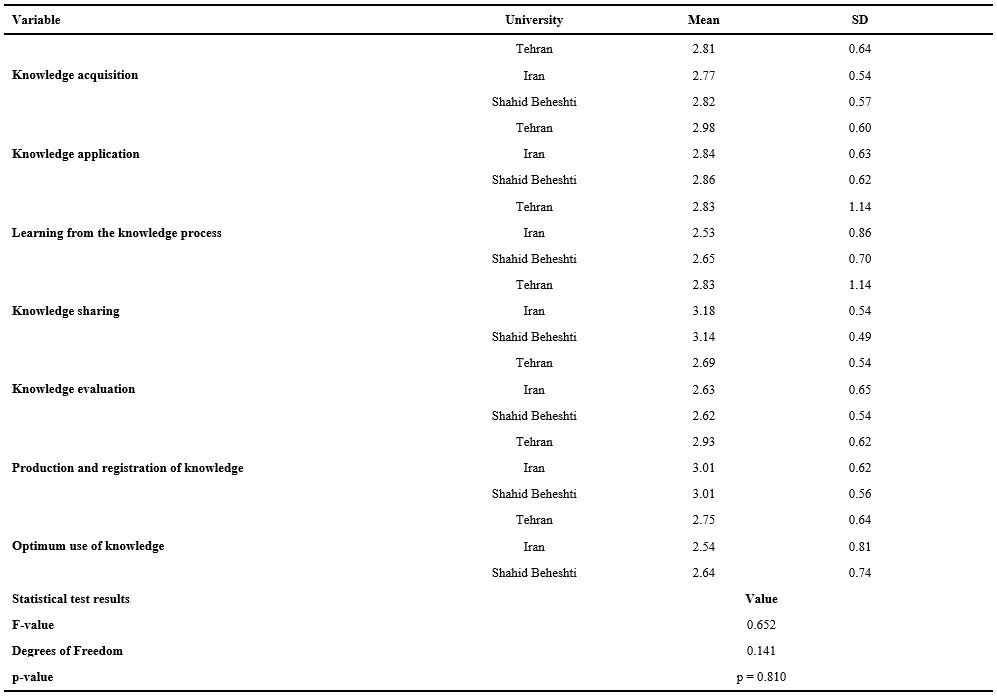

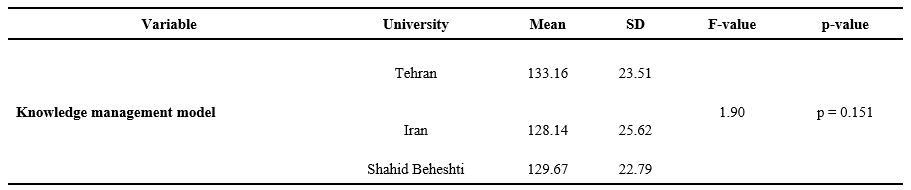

Table 3. One-way analysis of variance results comparing university effect on knowledge management level

Note: One-way ANOVA test was used to compare the effect of the university factor on the level of knowledge management.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; F, analysis of variance test; p, probability-value.

Note: MANOVA test was used to compare the knowledge management components in the courses based on the graduates' responses.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; F, analysis of variance test; p, probability-value.

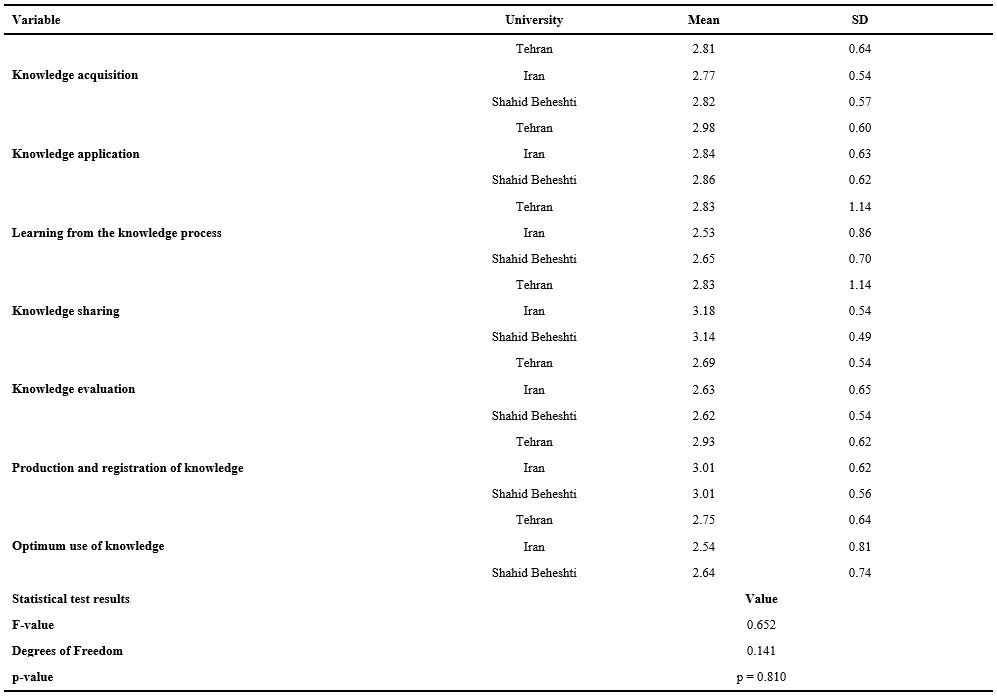

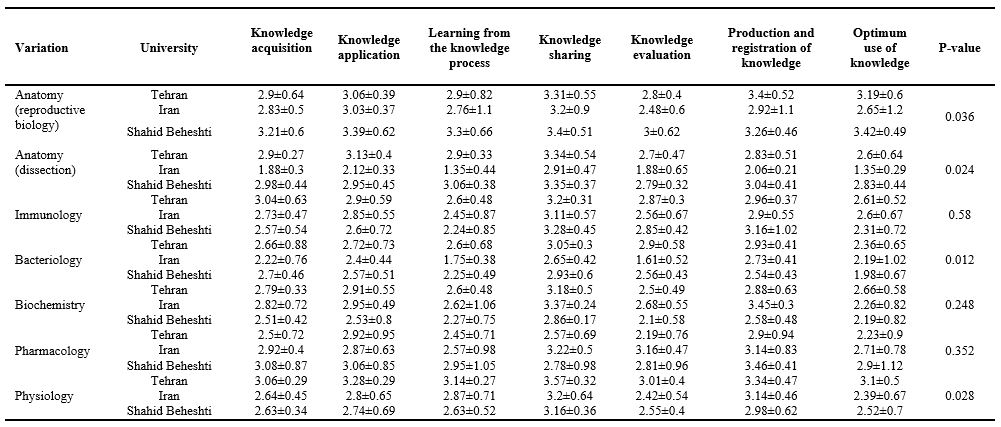

Table 5. Comparison of the average (± standard deviation) of knowledge management components in Ph.D. courses.

The findings showed that many participants felt the curricula were overly focused on theoretical instruction with limited opportunities for hands-on practice. Respondents frequently cited a disconnect between course content and real-world demands. Many participants mentioned that limited access to up-to-date laboratory facilities hindered innovation and creativity. Several respondents perceived the curriculum as rigid and not good for critical thinking or innovation.

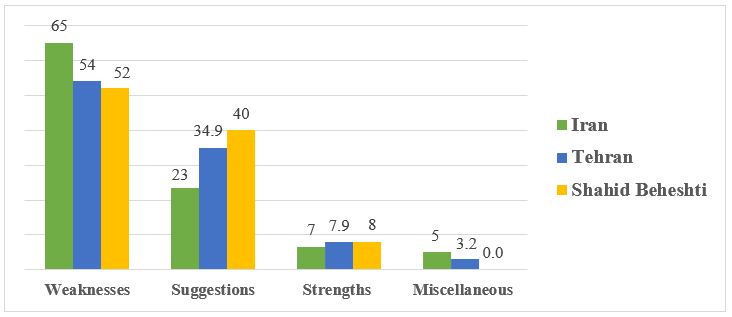

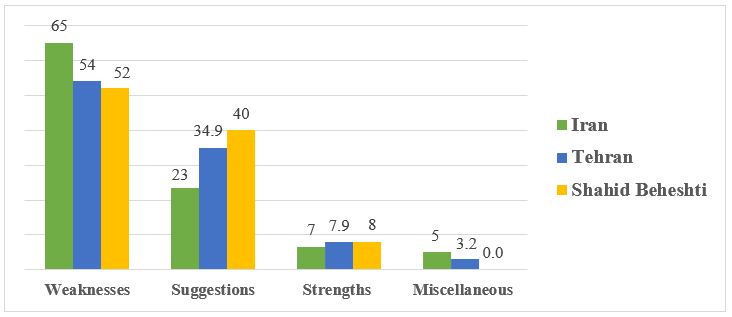

The frequency analysis revealed that weaknesses made up the most common response category across all three universities, particularly at IUMS (65% of comments). In contrast, strengths comprised less than 10% of responses at each institution, most often referring to isolated efforts such as journal clubs or up-to-date seminars led by select faculty members.

Figure 1. The frequency (%) of participants' comments categorized into the four main codes: weaknesses, suggestions, strengths, and miscellaneous points.

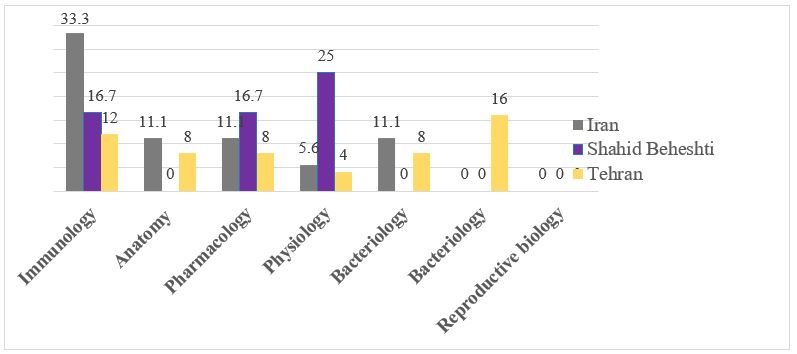

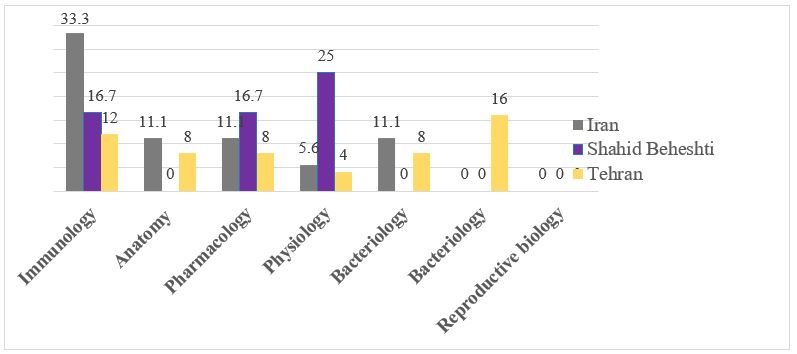

Figure 2. The frequency (%) of participants' responses to the qualitative section of the questionnaire, categorized by fields of basic medical sciences.

Overall, the qualitative data highlighted several critical areas for improvement in PhD curriculum design, particularly regarding relevance, engagement, infrastructure, and innovation. These findings contextualize the lower mean scores seen for "knowledge evaluation" and "learning from the knowledge process" in the quantitative phase and back up the need for complete curriculum reform. Regarding strengths, graduates from the Physiology department at IUMS and those in Pharmacology and Immunology at TUMS and SBUMS highlighted the inclusion of up-to-date topics by some professors and the regular organization of journal clubs and seminars. They believed that these journal clubs contribute to knowledge production, increase familiarity with global trends, and foster innovation and creativity among students.

Discussion

This study aimed to check the feasibility and implementation of a questionnaire designed to check the effectiveness of PhD courses in the specialized fields of basic medical sciences in Iran, with a focus on knowledge management among graduates. In the first phase of the study, a 38-item questionnaire was built, showing good validity with a CVI of 0.86, a CVR between 0.5 and 1, and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.935. While several researchers have attempted to create models that combine various aspects of knowledge management, no specific questionnaire has been designed to check syllabi. For instance, Aziz et al. [8] built a reliable and valid knowledge management model for companies, categorizing employees into strategic, executive, and operational levels. Their questionnaire provides a complete view of knowledge management in organizations. In a similar study, Karamitri et al. [23] built a valid and appropriate questionnaire for checking knowledge management processes in health organizations, focusing on dimensions such as perceptions of knowledge management, internal and external motivations, knowledge sharing, cooperation, leadership, organizational culture, and barriers.

The results of the present study showed that graduates from TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS rated the effectiveness of the PhD curriculum on knowledge management higher than the average scores reported in previous studies [23–29]. No statistically significant differences were seen (p > 0.05) among the universities checked in our study, showing similar effectiveness in terms of knowledge management. In a study by Kim et al. [26] on the quality of nursing doctoral curricula and related references, undesirable outcomes were reported for knowledge management and its components. Similarly, Wilson et al. [18], in their study on knowledge management in higher education institutions in Tanzania, found that both academic and non-academic staff at the MBA University of Science and Technology were unfamiliar with knowledge management practices. Studies by Asadi et al. [28] at TUMS hospitals and Vali et al. [29] at Kerman University of Medical Sciences reported average or below-average evaluations of knowledge management. In contrast, Davoodi et al. [10] found that knowledge management at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences was rated highly, with a mean of 3.16, which aligns with the findings of the present study. The differences across studies seen may be attributed to variations in organizational cultures, management and leadership styles, and the differing quality improvement and accreditation processes across institutions.

Among the components of the knowledge management model, "knowledge sharing" received the highest scores, with mean values of 3.2 at TUMS, 3.18 at IUMS, and 3.14 at SBUMS. No statistically significant differences were seen among these universities (p > 0.05). Several studies have also reported this component as one of the highest-scoring items [23, 30–32]. This suggests that the PhD curricula at these universities are well-suited for making easier the sharing of existing knowledge and its transfer to graduates. Alhammad et al. [30] looked into knowledge sharing among educational and administrative staff in Jordanian universities, identifying seven components: interactions, organizational experience, teamwork, creativity, positive attitudes toward knowledge sharing, knowledge about knowledge sharing, and knowledge sharing behavior. Their study revealed that educational staff were less willing to share knowledge compared to administrative staff. In a study by Kanzler et al. [33], knowledge sharing within a higher education institution in Mauritius was made easier through departmental meetings, curriculum discussions, annual research seminars, conferences, and journal publications. However, many organizations face challenges in knowledge sharing due to an inadequate organizational culture, which requires careful planning and attention. Knowledge sharing, which bridges knowledge management and creativity, is critical for creating a competitive advantage in today's world. To back up effective knowledge sharing, organizations need appropriate tools and techniques, such as knowledge bases (e.g., encyclopedias), collaborative virtual workspaces, knowledge portals, physical collaborative spaces, and learning repositories [33].

"Knowledge evaluation" in PhD courses in the fields of anatomy (reproductive biology), bacteriology, biochemistry, and physiology was found to be unsatisfactory according to university graduates. The mean score for this component in anatomy (reproductive biology) and bacteriology at IUMS was significantly lower than those at TUMS and SBUMS. Also, the mean score for physiology at IUMS was significantly lower than at TUMS (p < 0.05). These findings are consistent with studies by Mirghafoori et al. [34] and Mohammadi et al. [35]. The results highlight the need for these academic disciplines to set appropriate standards for checking both existing and future knowledge.

The results showed that the "best use of knowledge/elimination of outdated knowledge" component in the PhD course in the field of anatomy (dissection) was deemed unsatisfactory by the graduates. The mean score for this component at IUMS was significantly lower than at TUMS and SBUMS (p < 0.05). This component has not been included in other knowledge management models and has received limited attention in literature. However, it is important to focus on the elimination of outdated knowledge and the creation of repositories to archive such information. Identifying and removing obsolete guidelines, instructions, or directives, and replacing them with more effective other options, shows the "optimum use of knowledge/elimination of outdated knowledge" [35]. The component of "learning from the knowledge process" in the PhD course in the field of immunology was also considered unsatisfactory by the university graduates, although no statistically significant difference was seen (p > 0.05). The lack of practical units, short-term training courses, limited opportunities for interaction and teamwork, and not enough evaluation of graduates' performance may contribute to this outcome. Addressing these factors could lead to more effective growth of knowledge management in this field.

The relatively lower mean scores seen in the knowledge evaluation and knowledge advancement components, particularly at IUMS and SBUMS, may be related to critical gaps in curriculum implementation. These findings may result from a lack of, or poorly structured, checking mechanisms, as well as minimal opportunities for practice-based learning. The PhD students surveyed reported limited exposure to outcome-based learning strategies, insufficient feedback systems, and inadequate encouragement for critical thinking and knowledge integration. This aligns with previous studies reporting that traditional lecture-based formats, without practical checking or innovative tasks, often yield poor learning outcomes [11, 12]. It has been suggested that medical universities could carry out formative checking frameworks, problem-based learning, interdisciplinary case discussions, and continuous performance-based evaluations to address these issues [11, 12, 36–39]. Also, encouraging students to take on research projects and structured reflective practice can improve knowledge advancement and enable them to transform theoretical input into applied understanding and innovation [11, 12, 36–39].

Given the crucial role of post-graduation experience—particularly for PhD graduates who often lead various health-related or non-health-related organizations—providing short-term practical training courses within departments, supervised by experienced staff, is essential. Universities of Medical Sciences play a key role in integrating knowledge management into their mission, vision, and strategic plans across all departments. The successful implementation of knowledge management can significantly improve the application of systematic knowledge within the medical sciences field. The health system, being dynamic and continuously evolving, needs individuals with advanced knowledge and skills to deliver effective services.

Previous studies have shown that one of the key challenges for students during clinical training is bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, which can cause significant stress. According to Tessema [40], several factors affect students' satisfaction with the curriculum, including its structure and quality, content, diversity, opportunities for experiential learning, and the professional and scientific perspectives of both students and faculty [41]. Positive talking and mutual understanding between professors and students, as well as curricula built based on scientific evidence, contribute significantly to students' professional growth. The findings from the descriptive section of the present study align with these results, stressing the need to revise curricula to improve educational quality and create highly qualified graduates for the health system.

In the present study, although knowledge management in the curriculum—as perceived by PhD students at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS—was found to be above the average level, certain dimensions remain unsatisfactory. It is recommended that universities focus on updating knowledge sources, adding modern educational techniques, and ensuring that course content aligns with the modern needs of society. Also, providing practical and laboratory units, along with building specific standards to remove unnecessary and repetitive content, should be put first. By addressing the infrastructural aspects of knowledge management, universities can create an environment good for its full implementation and integration.

Conclusion

In terms of objectives, content, implementation, and evaluation, the approved curricula for basic sciences and graduate studies need periodic review from various perspectives, one of which is knowledge management. This study facilitated the design and validation of a questionnaire specifically focused on this area.

Based on the results, the questionnaire is a reliable and standardized tool for checking the PhD curriculum in specialized fields of the basic medical sciences at Tehran, Iran, and SBUMS” is unclear (Tehran and Iran are not parallel with SBUMS).

Likely you mean TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS. However, some aspects—such as evaluation, elimination of outdated knowledge, and learning from knowledge—are perceived as unsatisfactory and require more focused planning and attention.

Carrying out knowledge management frameworks within medical universities, where knowledge sharing is critical, will lead to improved service delivery and finally foster better learning, teaching, and research outcomes.

Ethical considerations

The modern research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch (Registration No. IAU.TNB.REC.1398.009).

Consent was received from the participants, and the anonymity of the questionnaires and the confidentiality of information were ensured.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

None.

Acknowledgment

We extend our sincere gratitude to all those who contributed to the successful completion of this research, including the professors and specialists in information science and epistemology, as well as the faculty members specializing in basic medical sciences.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

SS, and FS conceptualized and designed the study. SS collected the data, while FS and AG analyzed the data. All authors met the standards for authorship and contributed to preparing the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was excerpted from a PhD thesis and was funded by Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch, Tehran, Iran (No: 15721717971007).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Background & Objective: Checking the quality and dynamics of higher education curricula and checking the effectiveness of courses provide valuable feedback for improving educational standards. This study aimed to design and carry out a questionnaire to investigate and compare the effectiveness of PhD. curricula in encouraging knowledge management, as perceived by graduates of medical sciences universities in Iran.

Materials & Methods: A questionnaire based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model was built, comprising 38 items. The Content Validity Index (CVI), Content Validity Ratio (CVR), and question clarity were checked. Internal consistency and reliability were confirmed using Cronbach's alpha and correlation coefficients. The finalized questionnaire was distributed to 221 PhD graduates in various fields of basic medical sciences from Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS). Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results: The questionnaire consisted of seven components, with a CVR of 0.72, CVI of 0.86, and clarity score of 0.82. The reliability of the questionnaire was strong, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.935, and a positive, significant correlation was seen among its components (p < 0.01). The mean scores for knowledge management in PhD courses, as rated by graduates, were similar across the three universities and above average. The highest mean scores were related to the "knowledge sharing" component (TUMS:3.2, IUMS:3.18, and SBUMS:3.14). The lowest mean scores were seen for the "learning from the knowledge process" component (IUMS:2.53, and SBUMS:2.65), and the "knowledge evaluation" component (TUMS:2.69).

Conclusion: The effectiveness of PhD curricula in encouraging knowledge management was rated above average by graduates of the investigated medical universities. However, the results highlight the need for greater stress on knowledge evaluation, knowledge elimination, and learning processes to improve the overall effectiveness of these programs.

Introduction

Knowledge is a valuable resource, and its transformation from raw data into actionable knowledge depends on effective human management [1]. With the transition from the industrial age to the information era, knowledge has become a key driver of competitiveness for organizations and nations. Administration provides a platform for creating, checking, presenting, disseminating, and applying knowledge to benefit both organizations and clients [2, 3].

As a result, knowledge management has gained increasing importance and has become a central concern for organizations in recent years [4].

Various definitions of knowledge management stress its evolution, implementation, workflow, or technological aspects [2, 5]. Alavi and Leidner described it as the process of converting data into information and then into knowledge [1]. This process includes creating internal knowledge, getting external knowledge, storing and updating knowledge, and sharing it across systems [6]. Overall, knowledge management identifies values that improve products and services through the effective use of intellectual resources [7].

In a knowledge-based society, the role of knowledge management goes beyond enterprises [8]. Within education, it makes working together easier, effective use of knowledge, and transformation of personal knowledge into collective knowledge, thereby fostering innovation [9]. Universities, as the core institutions of higher education, play a vital role in knowledge production and dissemination, directly affecting societal growth [10]. Because education is basic to societal progress, curriculum quality—including its design, delivery, and outcomes—remains critical [11]. A curriculum provides structured pathways for knowledge and skill acquisition, shaping values and attitudes. Haav et al. identified two main objectives of higher education: preparing skilled professionals and growing engaged citizens [12]. To meet modern demands, curricula must be dynamic and continuously improved, which needs integration of knowledge management principles [13].

Survival in today's competitive environment depends on employee knowledge and skills. In universities and institutions, intellectual capital must be managed effectively by embedding knowledge into curricula, encouraging learning, working together, and innovation [14]. This is especially important in doctoral education, which addresses evolving societal needs amid technological advances and the rapid expansion of knowledge [15]. In health sciences, specialized doctoral programs are crucial due to healthcare complexities, demographic changes, and the centrality of human health in national growth.

Medical science universities must deliver curricula that adapt to external changes while keeping high quality. Curriculum evaluation is essential to refine content, improve implementation, and improve teaching ways. Adding feedback from students and faculty further guides improvement. Although tools exist for checking knowledge management in other fields [16], there is a lack of reliable instruments tailored to checking knowledge management in PhD graduates of medical sciences. This gap hinders efforts to strengthen postgraduate education and knowledge production.

So, the present study aimed to design and check a reliable questionnaire to check knowledge management components in PhD programs of basic medical sciences. By addressing this gap, the study provides university administrators with insights into curriculum strengths and weaknesses, helping efforts to improve educational quality and institutional performance.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The present study is applied in nature and uses a mixed- methods approach, adding both quantitative and qualitative components. In the first stage, a questionnaire was built based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model, and its validity and reliability were checked. In the second stage, the validated questionnaire was used to check the effectiveness of the PhD curriculum in terms of knowledge management. The study focused on specialized fields within the basic medical sciences at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS).

Participants and sampling

The study population comprised experts and professors in information science and knowledge studies, as well as specialists in basic sciences and graduate studies, including members of the curriculum evaluation committee.

Inclusion criteria were faculty members from these disciplines who served on the curriculum evaluation committee, while the exclusion standard was incomplete questionnaire responses. Convenience sampling was used because of limited access to eligible experts across faculties and the necessity to get timely responses from a specialized population. A total of 23 experts took part: 15 from information science and knowledge studies and 8 from basic sciences and graduate studies.

Tools/Instruments

The data collection tool was a researcher-built questionnaire based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model [17]. To build this tool, various dimensions of knowledge management were identified through a literature review and qualitative panel discussions.

The literature review was performed by searching keywords in the "Scopus," "PubMed," "ScienceDirect,"

"Google Scholar," "Medline," "Embase," "Web of Science," and "Cochrane" databases. The keywords, used alone and in combination, were: "effectiveness," "PhD curricula," "curricula," "curriculum," "knowledge management," "medical universities," "medical sciences," and "questionnaire."

We found 345 articles and excluded 266 due to unrelated content, 18 due to incomplete presentation of results relevant to our study, and 12 due to unavailability of the main text or because they were in languages other than English or Persian. Finally, 49 articles remained for further checking.

An early questionnaire comprising 64 questions was created.

To ensure the clarity and interpretability of questionnaire items, Cognitive Interviews (CI) were done between the authors and five PhD graduates in basic medical sciences from different specializations (anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, and immunology). Using think-aloud and verbal probing techniques, participants were asked to clearly articulate their understanding of each item, highlight ambiguities, and suggest improvements.

These interviews revealed issues such as vague terminology, double-barreled questions, and redundant phrasing.

Based on the feedback, items were revised to improve clarity, relevance, and consistency with the intended knowledge management dimensions. This CI phase played a crucial role in improving the content validity and user-friendliness of the final 38-item instrument (provided in the Appendix 1 as a supplementary table). After adding the suggested revisions, the final version of the questionnaire, consisting of 38 items, was approved by the authors.

For the quantitative content validity of the questionnaire, experts were asked to complete forms for the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI), and to provide comments on each item in the designated box or, if necessary, more generally at the end of the questionnaire. For CVR, the Lawshe table [18] was used, where a score above 0.42 was considered acceptable based on the critical value specified. CVI was checked using the method provided by Polit et al. [19], in which experts rated each item on a 4-point scale for relevance (1 = not relevant to 4 = highly relevant).

The item-level CVI was calculated as the proportion of experts rating the item as either 3 or 4. A score of 0.78 or higher was considered acceptable. To check the clarity of the questionnaire, experts rated each item on a four-point scale (completely clear, clear, relatively clear, and unclear).

The clarity score was calculated by dividing the number of experts who considered each item either "completely clear" or "clear" by the total number of experts. Based on various sources, an acceptable clarity score for a new tool was 0.8 [20, 21].

For checking the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha was used, with an acceptable value set at 0.8 or higher [22].

To check construct validity, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using principal component analysis with varimax rotation [22]. Sampling adequacy was backed up by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure (0.842), and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 3210.4, p < 0.001), confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, and items with loadings ≥ 0.40 were retained.

The final solution identified four factors that together accounted for 68.4% of the total variance.

The overall internal consistency was acceptable, with Cronbach's alpha = 0.82.

To check item-level quality and ensure rigor, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was applied to score each question.

Five PhD graduates from different medical disciplines checked each item regarding three dimensions: 1) relevance to the knowledge management construct, 2) clarity and wording precision, and 3) practical applicability within the context of PhD curricula in medical universities. Each item was rated between 1 and 10, with 10 showing the highest level and contextual quality.

Final scores were averaged across the evaluators. Items receiving a CASP score of 8 or higher were retained without modification, as they showed enough conceptual and linguistic quality.

On the other hand, items scoring below 8 were reviewed and revised for clarity or removed if deemed redundant or misaligned with the study objectives.

The CASP scoring process complemented the CVR and CVI analyses by adding expert judgment on the practical utility and interpretability of the questionnaire items.

In summary, the questionnaire was built using a multi-step process informed by the AMEE Guide No. 87. The growth stages included:

After confirming the reliability of the questionnaire, the opinions of graduates were checked across various knowledge management components.

Responses were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "very little" to "very much."

For this purpose, 221 PhD graduates from various departments of basic medical sciences—including anatomy, parasitology, immunology, bacteriology, biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology—at the medical faculties of TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS were included in the study. These graduates had completed all mandatory courses before the first or second semester of the 2018–2019 academic year and were selected through convenience sampling. To ensure the quality of the research, a final open-ended question was included in the questionnaire, focusing on graduates' opinions regarding the effect of the PhD curriculum on encouraging creativity, innovation, and knowledge. This question aimed to capture participants' views in four areas: weaknesses, suggestions, strengths, and other comments.

Graduates from each field answered this question descriptively, thinking about the curriculum relevant to their specific area of study.

Qualitative content analysis

The open-ended final question of the questionnaire was designed to check the effect of the PhD curriculum on creativity, innovation, and knowledge advancement. The responses were subjected to qualitative content analysis. Participant responses were coded inductively using content analysis techniques and categorized into four main themes: 1) theoretical overload with minimal application, 2) misalignment with societal and market needs, 3) lack of modern laboratory infrastructure, and 4) minimal fostering of creativity.

Data analysis

SPSS version 22 was used to analyze the questionnaire data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to check the normality of the data. Then, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated to assess the reliability of the data. To compare knowledge management components across different courses, a one-sample t-test and Friedman's test were used. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered for all statistical analyses.

Results

The CVR results were calculated to fall within the acceptable range of 0.5–1, with a mean of 0.72. The CVI values, with a mean of 0.86, and the clarity score, with a mean of 0.82, were both within acceptable ranges. The overall content validity of the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.8 (Table 1), showing that the researcher-built questionnaire used in this study was validated.

Cronbach's alpha for all seven components of knowledge management ranged from 0.661 to 0.811, showing acceptable reliability across the components. Also, the overall Cronbach's alpha for the 38 questions covering the seven components was calculated to be 0.935, showing the high reliability of the questionnaire used in this study (Table 1). The CASP scores for each question are presented in Table 1.

The mean CASP score across all items was 8.7, showing a generally high level of expert agreement on the relevance, clarity, and applicability of the items. Specifically, 33 out of 38 items received scores of ≥ 8, confirming their appropriateness for inclusion without revision.

The five items with CASP scores between 7 and 8 were re-checked and slightly revised for wording clarity based on expert feedback received during the cognitive interviewing phase.

Table 1. Content validity ratio, content validity index, clarity, Cronbach's Alpha, and CASP score for knowledge management capability questionnaire itemsAs a result, knowledge management has gained increasing importance and has become a central concern for organizations in recent years [4].

Various definitions of knowledge management stress its evolution, implementation, workflow, or technological aspects [2, 5]. Alavi and Leidner described it as the process of converting data into information and then into knowledge [1]. This process includes creating internal knowledge, getting external knowledge, storing and updating knowledge, and sharing it across systems [6]. Overall, knowledge management identifies values that improve products and services through the effective use of intellectual resources [7].

In a knowledge-based society, the role of knowledge management goes beyond enterprises [8]. Within education, it makes working together easier, effective use of knowledge, and transformation of personal knowledge into collective knowledge, thereby fostering innovation [9]. Universities, as the core institutions of higher education, play a vital role in knowledge production and dissemination, directly affecting societal growth [10]. Because education is basic to societal progress, curriculum quality—including its design, delivery, and outcomes—remains critical [11]. A curriculum provides structured pathways for knowledge and skill acquisition, shaping values and attitudes. Haav et al. identified two main objectives of higher education: preparing skilled professionals and growing engaged citizens [12]. To meet modern demands, curricula must be dynamic and continuously improved, which needs integration of knowledge management principles [13].

Survival in today's competitive environment depends on employee knowledge and skills. In universities and institutions, intellectual capital must be managed effectively by embedding knowledge into curricula, encouraging learning, working together, and innovation [14]. This is especially important in doctoral education, which addresses evolving societal needs amid technological advances and the rapid expansion of knowledge [15]. In health sciences, specialized doctoral programs are crucial due to healthcare complexities, demographic changes, and the centrality of human health in national growth.

Medical science universities must deliver curricula that adapt to external changes while keeping high quality. Curriculum evaluation is essential to refine content, improve implementation, and improve teaching ways. Adding feedback from students and faculty further guides improvement. Although tools exist for checking knowledge management in other fields [16], there is a lack of reliable instruments tailored to checking knowledge management in PhD graduates of medical sciences. This gap hinders efforts to strengthen postgraduate education and knowledge production.

So, the present study aimed to design and check a reliable questionnaire to check knowledge management components in PhD programs of basic medical sciences. By addressing this gap, the study provides university administrators with insights into curriculum strengths and weaknesses, helping efforts to improve educational quality and institutional performance.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The present study is applied in nature and uses a mixed- methods approach, adding both quantitative and qualitative components. In the first stage, a questionnaire was built based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model, and its validity and reliability were checked. In the second stage, the validated questionnaire was used to check the effectiveness of the PhD curriculum in terms of knowledge management. The study focused on specialized fields within the basic medical sciences at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS).

Participants and sampling

The study population comprised experts and professors in information science and knowledge studies, as well as specialists in basic sciences and graduate studies, including members of the curriculum evaluation committee.

Inclusion criteria were faculty members from these disciplines who served on the curriculum evaluation committee, while the exclusion standard was incomplete questionnaire responses. Convenience sampling was used because of limited access to eligible experts across faculties and the necessity to get timely responses from a specialized population. A total of 23 experts took part: 15 from information science and knowledge studies and 8 from basic sciences and graduate studies.

Tools/Instruments

The data collection tool was a researcher-built questionnaire based on the components of the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model [17]. To build this tool, various dimensions of knowledge management were identified through a literature review and qualitative panel discussions.

The literature review was performed by searching keywords in the "Scopus," "PubMed," "ScienceDirect,"

"Google Scholar," "Medline," "Embase," "Web of Science," and "Cochrane" databases. The keywords, used alone and in combination, were: "effectiveness," "PhD curricula," "curricula," "curriculum," "knowledge management," "medical universities," "medical sciences," and "questionnaire."

We found 345 articles and excluded 266 due to unrelated content, 18 due to incomplete presentation of results relevant to our study, and 12 due to unavailability of the main text or because they were in languages other than English or Persian. Finally, 49 articles remained for further checking.

An early questionnaire comprising 64 questions was created.

To ensure the clarity and interpretability of questionnaire items, Cognitive Interviews (CI) were done between the authors and five PhD graduates in basic medical sciences from different specializations (anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, and immunology). Using think-aloud and verbal probing techniques, participants were asked to clearly articulate their understanding of each item, highlight ambiguities, and suggest improvements.

These interviews revealed issues such as vague terminology, double-barreled questions, and redundant phrasing.

Based on the feedback, items were revised to improve clarity, relevance, and consistency with the intended knowledge management dimensions. This CI phase played a crucial role in improving the content validity and user-friendliness of the final 38-item instrument (provided in the Appendix 1 as a supplementary table). After adding the suggested revisions, the final version of the questionnaire, consisting of 38 items, was approved by the authors.

For the quantitative content validity of the questionnaire, experts were asked to complete forms for the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI), and to provide comments on each item in the designated box or, if necessary, more generally at the end of the questionnaire. For CVR, the Lawshe table [18] was used, where a score above 0.42 was considered acceptable based on the critical value specified. CVI was checked using the method provided by Polit et al. [19], in which experts rated each item on a 4-point scale for relevance (1 = not relevant to 4 = highly relevant).

The item-level CVI was calculated as the proportion of experts rating the item as either 3 or 4. A score of 0.78 or higher was considered acceptable. To check the clarity of the questionnaire, experts rated each item on a four-point scale (completely clear, clear, relatively clear, and unclear).

The clarity score was calculated by dividing the number of experts who considered each item either "completely clear" or "clear" by the total number of experts. Based on various sources, an acceptable clarity score for a new tool was 0.8 [20, 21].

For checking the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha was used, with an acceptable value set at 0.8 or higher [22].

To check construct validity, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using principal component analysis with varimax rotation [22]. Sampling adequacy was backed up by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure (0.842), and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 3210.4, p < 0.001), confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, and items with loadings ≥ 0.40 were retained.

The final solution identified four factors that together accounted for 68.4% of the total variance.

The overall internal consistency was acceptable, with Cronbach's alpha = 0.82.

To check item-level quality and ensure rigor, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was applied to score each question.

Five PhD graduates from different medical disciplines checked each item regarding three dimensions: 1) relevance to the knowledge management construct, 2) clarity and wording precision, and 3) practical applicability within the context of PhD curricula in medical universities. Each item was rated between 1 and 10, with 10 showing the highest level and contextual quality.

Final scores were averaged across the evaluators. Items receiving a CASP score of 8 or higher were retained without modification, as they showed enough conceptual and linguistic quality.

On the other hand, items scoring below 8 were reviewed and revised for clarity or removed if deemed redundant or misaligned with the study objectives.

The CASP scoring process complemented the CVR and CVI analyses by adding expert judgment on the practical utility and interpretability of the questionnaire items.

In summary, the questionnaire was built using a multi-step process informed by the AMEE Guide No. 87. The growth stages included:

- Identification of research objectives and questions aligned with the Bukowitz and Williams knowledge management model.

- Literature review to tell item generation and model suitability.

- Qualitative panel discussions to ensure contextual relevance.

- Item generation based on conceptual mapping of model components.

- Cognitive Interviews (CI): Five PhD graduates from different medical disciplines took part in CI to test question clarity, logic, and interpretation.

- Content validity checking using CVI and CVR metrics.

- Pilot testing and psychometric checking through reliability analysis and correlation matrices.

After confirming the reliability of the questionnaire, the opinions of graduates were checked across various knowledge management components.

Responses were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "very little" to "very much."

For this purpose, 221 PhD graduates from various departments of basic medical sciences—including anatomy, parasitology, immunology, bacteriology, biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology—at the medical faculties of TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS were included in the study. These graduates had completed all mandatory courses before the first or second semester of the 2018–2019 academic year and were selected through convenience sampling. To ensure the quality of the research, a final open-ended question was included in the questionnaire, focusing on graduates' opinions regarding the effect of the PhD curriculum on encouraging creativity, innovation, and knowledge. This question aimed to capture participants' views in four areas: weaknesses, suggestions, strengths, and other comments.

Graduates from each field answered this question descriptively, thinking about the curriculum relevant to their specific area of study.

Qualitative content analysis

The open-ended final question of the questionnaire was designed to check the effect of the PhD curriculum on creativity, innovation, and knowledge advancement. The responses were subjected to qualitative content analysis. Participant responses were coded inductively using content analysis techniques and categorized into four main themes: 1) theoretical overload with minimal application, 2) misalignment with societal and market needs, 3) lack of modern laboratory infrastructure, and 4) minimal fostering of creativity.

Data analysis

SPSS version 22 was used to analyze the questionnaire data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to check the normality of the data. Then, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated to assess the reliability of the data. To compare knowledge management components across different courses, a one-sample t-test and Friedman's test were used. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered for all statistical analyses.

Results

The CVR results were calculated to fall within the acceptable range of 0.5–1, with a mean of 0.72. The CVI values, with a mean of 0.86, and the clarity score, with a mean of 0.82, were both within acceptable ranges. The overall content validity of the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.8 (Table 1), showing that the researcher-built questionnaire used in this study was validated.

Cronbach's alpha for all seven components of knowledge management ranged from 0.661 to 0.811, showing acceptable reliability across the components. Also, the overall Cronbach's alpha for the 38 questions covering the seven components was calculated to be 0.935, showing the high reliability of the questionnaire used in this study (Table 1). The CASP scores for each question are presented in Table 1.

The mean CASP score across all items was 8.7, showing a generally high level of expert agreement on the relevance, clarity, and applicability of the items. Specifically, 33 out of 38 items received scores of ≥ 8, confirming their appropriateness for inclusion without revision.

The five items with CASP scores between 7 and 8 were re-checked and slightly revised for wording clarity based on expert feedback received during the cognitive interviewing phase.

Note: To assess item-level quality and ensure methodological rigor, the CASP checklist was applied to score each question. To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha was used.

Abbreviations: CVR, content validity ratio; CVI, content validity index; CASP, critical appraisal skills programme; Q, question.

Abbreviations: CVR, content validity ratio; CVI, content validity index; CASP, critical appraisal skills programme; Q, question.

The evaluation of the correlations among the measured components, using a correlation matrix, revealed that all seven components were significantly correlated with each other and with the total scale score (p < 0.01). Also, the highest correlation coefficient was seen between the total knowledge management score and the knowledge application component (p < 0.01, r = 0.88), while the lowest correlation coefficient was found between the knowledge production and knowledge application components (p < 0.01, r = 0.48) (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation matrix between knowledge management components and total score

Note: To compare knowledge management components across different courses, a one-sample t-test and Friedman's test were employed. An asterisk (**) indicates that p < 0.01.

The results of the knowledge management study in courses, based on responses from PhD students in various fields of basic medical sciences at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS (Table 3), revealed that the mean scores seen at TUMS (133.16), IUMS (128.14), and SBUMS (129.67) were all higher than the assumed benchmark value (x̄ = 114). This indicates that, based on graduates’ responses, the potential for implementing the knowledge management model in the courses is above the expected level.

Table 3. One-way analysis of variance results comparing university effect on knowledge management level

Note: One-way ANOVA test was used to compare the effect of the university factor on the level of knowledge management.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; F, analysis of variance test; p, probability-value.

According to Table 4, the most frequently used component of knowledge management is "knowledge sharing," with mean scores of 3.2 at TUMS, 3.18 at IUMS, and 3.14 at SBUMS.

In contrast, the least frequently used components are "learning from the knowledge process", with a mean score of 2.53 at IUMS, and "knowledge evaluation", with mean scores of 2.69 at TUMS and 2.62 at SBUMS. Table 5 presents the mean ± standard deviation for each of the knowledge management components in the PhD courses at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS. According to these results, "knowledge sharing" remains the most frequently used component, and no significant statistical differences were seen among the universities (p > 0.05).

To complement the quantitative findings, responses to the final open-ended question of the questionnaire — regarding the effect of the PhD curriculum on creativity, innovation, and knowledge advancement — were subjected to qualitative content analysis.

A total of 85 participants (52 from TUMS, 18 from IUMS, and 15 from SBUMS) provided narrative feedback.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of variance results comparing knowledge management components across universitiesIn contrast, the least frequently used components are "learning from the knowledge process", with a mean score of 2.53 at IUMS, and "knowledge evaluation", with mean scores of 2.69 at TUMS and 2.62 at SBUMS. Table 5 presents the mean ± standard deviation for each of the knowledge management components in the PhD courses at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS. According to these results, "knowledge sharing" remains the most frequently used component, and no significant statistical differences were seen among the universities (p > 0.05).

To complement the quantitative findings, responses to the final open-ended question of the questionnaire — regarding the effect of the PhD curriculum on creativity, innovation, and knowledge advancement — were subjected to qualitative content analysis.

A total of 85 participants (52 from TUMS, 18 from IUMS, and 15 from SBUMS) provided narrative feedback.

Note: MANOVA test was used to compare the knowledge management components in the courses based on the graduates' responses.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; F, analysis of variance test; p, probability-value.

Table 5. Comparison of the average (± standard deviation) of knowledge management components in Ph.D. courses.

Abbreviations: P, probability-value

As shown in Figure 1, 34 responses (54%) from TUMS, 39 responses (65%) from IUMS, and 12 responses (52%) from SBUMS highlighted weaknesses. Only 5 responses (7.9%), 4 responses (6.67%), and 2 responses (8%) from TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS, respectively, were related to curriculum strengths. Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses from graduates in various fields of basic medical sciences at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS to the qualitative question. As shown, 33.3% of respondents were from the Immunology department at IUMS, 25% from the Physiology department at SBUMS, and 16% from the Biochemistry department at TUMS. Graduates in Reproductive Biology from all three universities provided no responses to the qualitative question.The findings showed that many participants felt the curricula were overly focused on theoretical instruction with limited opportunities for hands-on practice. Respondents frequently cited a disconnect between course content and real-world demands. Many participants mentioned that limited access to up-to-date laboratory facilities hindered innovation and creativity. Several respondents perceived the curriculum as rigid and not good for critical thinking or innovation.

The frequency analysis revealed that weaknesses made up the most common response category across all three universities, particularly at IUMS (65% of comments). In contrast, strengths comprised less than 10% of responses at each institution, most often referring to isolated efforts such as journal clubs or up-to-date seminars led by select faculty members.

Figure 1. The frequency (%) of participants' comments categorized into the four main codes: weaknesses, suggestions, strengths, and miscellaneous points.

Figure 2. The frequency (%) of participants' responses to the qualitative section of the questionnaire, categorized by fields of basic medical sciences.

Overall, the qualitative data highlighted several critical areas for improvement in PhD curriculum design, particularly regarding relevance, engagement, infrastructure, and innovation. These findings contextualize the lower mean scores seen for "knowledge evaluation" and "learning from the knowledge process" in the quantitative phase and back up the need for complete curriculum reform. Regarding strengths, graduates from the Physiology department at IUMS and those in Pharmacology and Immunology at TUMS and SBUMS highlighted the inclusion of up-to-date topics by some professors and the regular organization of journal clubs and seminars. They believed that these journal clubs contribute to knowledge production, increase familiarity with global trends, and foster innovation and creativity among students.

Discussion

This study aimed to check the feasibility and implementation of a questionnaire designed to check the effectiveness of PhD courses in the specialized fields of basic medical sciences in Iran, with a focus on knowledge management among graduates. In the first phase of the study, a 38-item questionnaire was built, showing good validity with a CVI of 0.86, a CVR between 0.5 and 1, and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.935. While several researchers have attempted to create models that combine various aspects of knowledge management, no specific questionnaire has been designed to check syllabi. For instance, Aziz et al. [8] built a reliable and valid knowledge management model for companies, categorizing employees into strategic, executive, and operational levels. Their questionnaire provides a complete view of knowledge management in organizations. In a similar study, Karamitri et al. [23] built a valid and appropriate questionnaire for checking knowledge management processes in health organizations, focusing on dimensions such as perceptions of knowledge management, internal and external motivations, knowledge sharing, cooperation, leadership, organizational culture, and barriers.

The results of the present study showed that graduates from TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS rated the effectiveness of the PhD curriculum on knowledge management higher than the average scores reported in previous studies [23–29]. No statistically significant differences were seen (p > 0.05) among the universities checked in our study, showing similar effectiveness in terms of knowledge management. In a study by Kim et al. [26] on the quality of nursing doctoral curricula and related references, undesirable outcomes were reported for knowledge management and its components. Similarly, Wilson et al. [18], in their study on knowledge management in higher education institutions in Tanzania, found that both academic and non-academic staff at the MBA University of Science and Technology were unfamiliar with knowledge management practices. Studies by Asadi et al. [28] at TUMS hospitals and Vali et al. [29] at Kerman University of Medical Sciences reported average or below-average evaluations of knowledge management. In contrast, Davoodi et al. [10] found that knowledge management at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences was rated highly, with a mean of 3.16, which aligns with the findings of the present study. The differences across studies seen may be attributed to variations in organizational cultures, management and leadership styles, and the differing quality improvement and accreditation processes across institutions.

Among the components of the knowledge management model, "knowledge sharing" received the highest scores, with mean values of 3.2 at TUMS, 3.18 at IUMS, and 3.14 at SBUMS. No statistically significant differences were seen among these universities (p > 0.05). Several studies have also reported this component as one of the highest-scoring items [23, 30–32]. This suggests that the PhD curricula at these universities are well-suited for making easier the sharing of existing knowledge and its transfer to graduates. Alhammad et al. [30] looked into knowledge sharing among educational and administrative staff in Jordanian universities, identifying seven components: interactions, organizational experience, teamwork, creativity, positive attitudes toward knowledge sharing, knowledge about knowledge sharing, and knowledge sharing behavior. Their study revealed that educational staff were less willing to share knowledge compared to administrative staff. In a study by Kanzler et al. [33], knowledge sharing within a higher education institution in Mauritius was made easier through departmental meetings, curriculum discussions, annual research seminars, conferences, and journal publications. However, many organizations face challenges in knowledge sharing due to an inadequate organizational culture, which requires careful planning and attention. Knowledge sharing, which bridges knowledge management and creativity, is critical for creating a competitive advantage in today's world. To back up effective knowledge sharing, organizations need appropriate tools and techniques, such as knowledge bases (e.g., encyclopedias), collaborative virtual workspaces, knowledge portals, physical collaborative spaces, and learning repositories [33].

"Knowledge evaluation" in PhD courses in the fields of anatomy (reproductive biology), bacteriology, biochemistry, and physiology was found to be unsatisfactory according to university graduates. The mean score for this component in anatomy (reproductive biology) and bacteriology at IUMS was significantly lower than those at TUMS and SBUMS. Also, the mean score for physiology at IUMS was significantly lower than at TUMS (p < 0.05). These findings are consistent with studies by Mirghafoori et al. [34] and Mohammadi et al. [35]. The results highlight the need for these academic disciplines to set appropriate standards for checking both existing and future knowledge.

The results showed that the "best use of knowledge/elimination of outdated knowledge" component in the PhD course in the field of anatomy (dissection) was deemed unsatisfactory by the graduates. The mean score for this component at IUMS was significantly lower than at TUMS and SBUMS (p < 0.05). This component has not been included in other knowledge management models and has received limited attention in literature. However, it is important to focus on the elimination of outdated knowledge and the creation of repositories to archive such information. Identifying and removing obsolete guidelines, instructions, or directives, and replacing them with more effective other options, shows the "optimum use of knowledge/elimination of outdated knowledge" [35]. The component of "learning from the knowledge process" in the PhD course in the field of immunology was also considered unsatisfactory by the university graduates, although no statistically significant difference was seen (p > 0.05). The lack of practical units, short-term training courses, limited opportunities for interaction and teamwork, and not enough evaluation of graduates' performance may contribute to this outcome. Addressing these factors could lead to more effective growth of knowledge management in this field.

The relatively lower mean scores seen in the knowledge evaluation and knowledge advancement components, particularly at IUMS and SBUMS, may be related to critical gaps in curriculum implementation. These findings may result from a lack of, or poorly structured, checking mechanisms, as well as minimal opportunities for practice-based learning. The PhD students surveyed reported limited exposure to outcome-based learning strategies, insufficient feedback systems, and inadequate encouragement for critical thinking and knowledge integration. This aligns with previous studies reporting that traditional lecture-based formats, without practical checking or innovative tasks, often yield poor learning outcomes [11, 12]. It has been suggested that medical universities could carry out formative checking frameworks, problem-based learning, interdisciplinary case discussions, and continuous performance-based evaluations to address these issues [11, 12, 36–39]. Also, encouraging students to take on research projects and structured reflective practice can improve knowledge advancement and enable them to transform theoretical input into applied understanding and innovation [11, 12, 36–39].

Given the crucial role of post-graduation experience—particularly for PhD graduates who often lead various health-related or non-health-related organizations—providing short-term practical training courses within departments, supervised by experienced staff, is essential. Universities of Medical Sciences play a key role in integrating knowledge management into their mission, vision, and strategic plans across all departments. The successful implementation of knowledge management can significantly improve the application of systematic knowledge within the medical sciences field. The health system, being dynamic and continuously evolving, needs individuals with advanced knowledge and skills to deliver effective services.

Previous studies have shown that one of the key challenges for students during clinical training is bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, which can cause significant stress. According to Tessema [40], several factors affect students' satisfaction with the curriculum, including its structure and quality, content, diversity, opportunities for experiential learning, and the professional and scientific perspectives of both students and faculty [41]. Positive talking and mutual understanding between professors and students, as well as curricula built based on scientific evidence, contribute significantly to students' professional growth. The findings from the descriptive section of the present study align with these results, stressing the need to revise curricula to improve educational quality and create highly qualified graduates for the health system.

In the present study, although knowledge management in the curriculum—as perceived by PhD students at TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS—was found to be above the average level, certain dimensions remain unsatisfactory. It is recommended that universities focus on updating knowledge sources, adding modern educational techniques, and ensuring that course content aligns with the modern needs of society. Also, providing practical and laboratory units, along with building specific standards to remove unnecessary and repetitive content, should be put first. By addressing the infrastructural aspects of knowledge management, universities can create an environment good for its full implementation and integration.

Conclusion

In terms of objectives, content, implementation, and evaluation, the approved curricula for basic sciences and graduate studies need periodic review from various perspectives, one of which is knowledge management. This study facilitated the design and validation of a questionnaire specifically focused on this area.

Based on the results, the questionnaire is a reliable and standardized tool for checking the PhD curriculum in specialized fields of the basic medical sciences at Tehran, Iran, and SBUMS” is unclear (Tehran and Iran are not parallel with SBUMS).

Likely you mean TUMS, IUMS, and SBUMS. However, some aspects—such as evaluation, elimination of outdated knowledge, and learning from knowledge—are perceived as unsatisfactory and require more focused planning and attention.

Carrying out knowledge management frameworks within medical universities, where knowledge sharing is critical, will lead to improved service delivery and finally foster better learning, teaching, and research outcomes.

Ethical considerations

The modern research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch (Registration No. IAU.TNB.REC.1398.009).

Consent was received from the participants, and the anonymity of the questionnaires and the confidentiality of information were ensured.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

None.

Acknowledgment

We extend our sincere gratitude to all those who contributed to the successful completion of this research, including the professors and specialists in information science and epistemology, as well as the faculty members specializing in basic medical sciences.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

SS, and FS conceptualized and designed the study. SS collected the data, while FS and AG analyzed the data. All authors met the standards for authorship and contributed to preparing the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was excerpted from a PhD thesis and was funded by Islamic Azad University of Tehran North Branch, Tehran, Iran (No: 15721717971007).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2025/01/21 | Accepted: 2025/09/30 | Published: 2025/11/19

Received: 2025/01/21 | Accepted: 2025/09/30 | Published: 2025/11/19

References

1. Tian J, Nakamori Y, Wierzbicki AP. Knowledge management and knowledge creation in academia: a study based on surveys in a Japanese research university. J Knowl Manag. 2009;13(2):76-92. [DOI:10.1108/13673270910942718]

2. Clarke AJ. Quality management practices and organizational knowledge management: a quantitative and qualitative investigation [dissertation]. Cincinnati (OH): Graduate College of :union: Institute & University; 2006.

3. Zins C. Conceptual approaches for defining data, information, and knowledge. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2007;58(4):479-93. [DOI:10.1002/asi.20508]

4. Kaba A, Ramaiah CK. Measuring knowledge acquisition and knowledge creation: a review of the literature. Lib Philos Pract. 2020;2020:4723.

5. Bose R. Knowledge management-enabled health care management systems: capabilities, infrastructure, and decision-support. Expert Syst Appl. 2003;24(1):59-71. [DOI:10.1016/S0957-4174(02)00083-0]

6. McCarthy AF. Knowledge management: evaluating strategies and processes used in higher education [dissertation]. Fort Lauderdale (FL): Nova Southeastern University; 2006.

7. Brooks F, Scott P. Knowledge work in nursing and midwifery: an evaluation through computer-mediated communication. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(1):83-97. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.003] [PMID]

8. Aziz DT, Bouazza A, Jabur NH, Hassan DS, Al Aufi DA. Development and validation of a knowledge management questionnaire. J Inf Stud Technol. 2018;2018(1):1-16. [DOI:10.5339/jist.2018.2]

9. McElroy MW. The new knowledge management. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2002.

10. Davoodi M, LotfiZadeh Z, Arab ZM. Knowledge management and its influencing factors in Ahvaz Jundishapur university of medical sciences. J JundiShapur Educ Dev. 2018;7(2):120-8.

11. Alamri MZ, Jhanjhi NZ, Humayun M. Digital curriculum importance for new era education. In: Jhanjhi NZ, editor. Employing recent technologies for improved digital governance. Hershey (PA): IGI Global; 2020. p. 1-18. [DOI:10.4018/978-1-7998-1851-9.ch001]

12. Haav K. Implementation of curriculum theory in formation of specialists in higher education. In: Cai Y, editor. Sustainable futures for higher education. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 305-9. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-96035-7_25]

13. Ngugi J, Goosen L. Modelling course-design characteristics, self-regulated learning and the mediating effect of knowledge-sharing behavior as drivers of individual innovative behavior. EURASIA J Math Sci Technol Educ. 2018;14(8):em1575. [DOI:10.29333/ejmste/92087]

14. Sánchez LE, André P. Knowledge management in environmental impact assessment agencies: a study in Québec, Canada. J Environ Assess Policy Manag. 2013;15(3):1350015. [DOI:10.1142/S1464333213500154]

15. Fathi VK, Khosravi BA, Hajatmand F. Evaluating internal quality of educational programs of PhD medical ethics curriculum from point of professors and students. Med Ethics. 2014;8(27):129-62.

16. Aharony N. Librarians' attitudes toward knowledge management. Coll Res Libr. 2011;72(2):111-26. [DOI:10.5860/crl-87]

17. Bukowitz WR, Williams RL. The Knowledge Management Fieldbook. London: Financial Times Prentice Hall; 1999.

18. Wilson FR, Pan W, Schumsky DA. Recalculation of the critical values for Lawshe's content validity ratio. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2012;45(3):197-210. [DOI:10.1177/0748175612440286]

19. Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459-67. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199] [PMID]

20. Rubio DM, Berg-Weger M, Tebb SS, Lee ES, Rauch S. Objectifying content validity: conducting a content validity study in social work research. Soc Work Res. 2003;27(2):94-104. [DOI:10.1093/swr/27.2.94]

21. Schutz AL, Counte MA, Meurer S. Development of a patient safety culture measurement tool for ambulatory health care settings: analysis of content validity. Health Care Manag Sci. 2007;10(2):139-49. [DOI:10.1007/s10729-007-9014-y] [PMID]

22. DeVellis RF, Thorpe CT. Scale development: theory and applications. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2021.

23. Karamitri I, Kitsios F, Talias MA. Development and validation of a knowledge management questionnaire for hospitals and other healthcare organizations. Sustainability. 2020;12(7):2730. [DOI:10.3390/su12072730]

24. Akhavan P, Hosnavi R, Sanjaghi ME. Identification of knowledge management critical success factors in Iranian academic research centers. Educ Bus Soc Contemp Middle East Issues. 2009;2(4):276-88. [DOI:10.1108/17537980911001107]

25. Wang Z, Wang N. Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Syst Appl. 2012;39(10):8899-908. [DOI:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.017]

26. Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim HK, et al. Quality of faculty, students, curriculum and resources for nursing doctoral education in Korea: a focus group study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(3):295-306. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.07.005] [PMID]

27. Charles W, Nawe J. Knowledge management (KM) practices in institutions of higher learning in Tanzania with reference to Mbeya university of science and technology. Univ Dar Salaam Lib J. 2017;12(1):48-65.

28. Asadi S, Mahmoudi M. Survey of the relationship of knowledge management and organizational creativity and innovation among the employees of Tehran university of medical sciences. J Hosp. 2018;17(1):97-108.

29. Vali L, Izadi A, Jahani Y, Okhovati M. Investigating knowledge management status among faculty members of Kerman university of medical sciences based on the Nonaka model in 2015. Electron Physician. 2016;8(8):2738-44. [DOI:10.19082/2738] [PMID] []

30. Alhammad F, Al Faori S, Abu Husan LS. Knowledge sharing in the Jordanian universities. J Knowl Manag Pract. 2009;10(3):1-9.

31. Fullwood R, Rowley J, Delbridge R. Knowledge sharing amongst academics in UK universities. J Knowl Manag. 2013;17(1):123-36. [DOI:10.1108/13673271311300831]

32. Cabrera EF, Cabrera A. Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2005;16(5):720-35. [DOI:10.1080/09585190500083020]

33. Kanzler S, Niedergassel B, Leker J. Knowledge sharing in academic R&D collaborations: does culture matter? J Chin Entrep. 2012;4(1):42-59. [DOI:10.1108/17561391211200902]

34. Mirghafoori SH, Nejad F, Sadeghi Arani Z. Performance evaluation of Yazd's health sector on applying knowledge management process. J Health Adm. 2010;13(39):79-88.

35. Mohammadi Ostani M, Shojafard A. A feasibility implementation of Bukowitz & William's knowledge management model and its impact on knowledge contribution in Qom province public libraries. Digit Smart Libr Res. 2019;6(3):59-68.

36. Boud D, Falchikov N. Aligning assessment with long‐term learning. Assess Eval High Educ. 2006;31(4):399-413. [DOI:10.1080/02602930600679050]

37. Hmelo-Silver CE. Problem-based learning: what and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev. 2004;16(3):235-66. [DOI:10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3]

38. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595-621. [DOI:10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2] [PMID]

39. Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):387-96. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMra054784] [PMID]

40. Tessema MT, Ready K, Yu W. Factors affecting college students' satisfaction with major curriculum: evidence from nine years of data. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2012;2(2):34-44.

41. Kuh GD. Assessing conditions to enhance educational effectiveness: the inventory for student engagement and success. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2005.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |