Fri, Jan 30, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 3 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(3): 5-13 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

T. Nafea E. Dental students' experiences of curriculum transition and educational challenges after COVID-19. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (3) :5-13

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2344-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2344-en.html

Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, Taibah University, Medinah, Saudi Arabia , EbtihajT.Nafea@researchergroup.co

Full-Text [PDF 492 kb]

(252 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (790 Views)

Full-Text: (26 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: The background of this research study involves past studies that highlight the struggle of students during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study outlines the challenges faced by dental students during the Covid-19 pandemic and highlights the struggles of dental students at Taibah University in Saudi Arabia regarding the implementation of a new curriculum that includes a three-semester system. Additionally, it explores the students' perspectives on the abrupt curriculum changes and the strategies they developed to adapt to these adjustments.

Materials & Methods: The methodology used in this study involved thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with ten students from the dental college at the university.

Results: The findings of this study showed that most of the dental students of Taibah University were not satisfied with the introduction of the new curriculum system.

Conclusion: The study recommends that any curriculum changes should be communicated effectively with both teachers and students to ensure that the new curriculum aligns with student needs. Additionally, both students and teachers should receive proper training in the use of new technologies to enhance education and better equip them to address future challenges.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on higher education systems globally, and universities were forced to quickly respond by making a transition from face-to-face teaching to remote and hybrid learning models [1]. These transitions were made to provide continuity of education in a period of crisis and were experienced across all fields, including clinical ones like dentistry [2]. In addition to the immediate transition to online education, some schools implemented more significant changes to their class schedules in an effort to mitigate educational loss and enhance system effectiveness [3].

At Taibah University in Saudi Arabia, the Faculty of Dentistry underwent a fundamental reorganization of its academic year, shifting from a traditional two-semester system to a three-semester format [4]. This transition was part of a broader national restructuring aligned with Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030, which aims to modernize and optimize educational institutions to meet new societal and workforce demands [5]. The change did not involve altering the curriculum itself; rather, it focused on restructuring and presenting the existing coursework in a more condensed and accelerated academic schedule [6].

This research does not refer to curriculum change in the traditional definition of altering learning outcomes, course content, or pedagogic strategies.

Rather, it explores a curricular framework shift, namely the reconstruction of the academic year into three semesters, and the instructional, psychological, and logistical hurdles that it caused dental students amid and following the pandemic. The differentiation is central to comprehending the emphasis and contribution of the research.

The need for this study is rooted in the paucity of previous research into students' experiences with such curricular structural changes. Most previous studies tackle remote learning challenges amidst COVID-19 but fail to consider the long-term effects of academic restructuring on clinical education programs [7- 9]. Given the demanding nature of dental education, where theoretical knowledge must be balanced with clinical practice, the transition to a three-semester model represents a significant change. This shift has potential implications for student performance, stress levels, and academic progress.

Hence, the aim of this research is to find out the experiences of dental students of Taibah University in going through this transition. The research seeks to record their perceptions regarding workload, modifications in clinical and theoretical training, psychological effects, and how they coped with the adjustments. The study seeks to answer the question: How did dental students at Taibah University experience and respond to the transition from a two-semester to a three-semester academic system during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This research utilized a qualitative descriptive approach through semi-structured interviews to investigate the experiences of dental students at Taibah University as they moved from a two-semester to a three-semester academic system within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of this approach was to allow in-depth personal views and subjective meanings of the restructuring of the academic environment, specifically concerning workload, stress, and coping mechanisms.

Participants and sampling

The research was carried out at the Taibah University College of Dentistry, a Saudi Arabian public university that is linked to the Ministry of Education.

The implementation of the curriculum reform into the three-semester system was carried out in accordance with national reforms outlined in Saudi Vision 2030. During the pandemic, the faculty employed Microsoft Teams and Blackboard platforms for communication and online learning. Nonetheless, some students complained that technical and communicative constraints hindered their capacity to interact effectively with instructors.

The purposive sampling method was applied when recruiting the students who had used both the two-semester and three-semester processes.

Ten students were selected to ensure a diverse representation of academic levels and genders. The participants were 6 females and 4 males, all in the 3rd or 4th year of their program of study in dentistry. These years were selected because this group of students had worked through preclinical training, were actively working on clinical and theoretical components of the curriculum, and, therefore, were appropriate informants for this study.

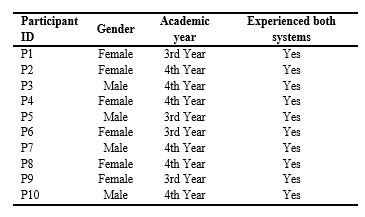

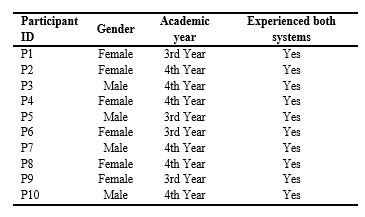

The study did not classify students by academic strength because of privacy concerns. Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the 10 participants who experienced both the two-semester and three-semester systems.

Table 1. Participant characteristics table

Data collection methods

Interviews were done in a secluded area, either face-to-face or through secure video conferencing tools based on student preference and accessibility. The interviews took anywhere from 30 to 45 minutes. The research team created an interview guide, which contained open-ended questions to elicit the views of the students regarding the three-semester system, how it affected their academic and clinical education, their well-being, and the support structures they utilized. Probing techniques to obtain more elaborate responses were employed. All the interviews were done by the author, who is a qualitative researcher trained and experienced in dental education research, and were audio-recorded with informed consent of the participants. Interviews were held in English.

Data analysis

The information gathered from the semi-structured interviews was coded and analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase inductive model outlined by Braun and Clarke, as discussed in a previous study [10]. The technique was selected because it was found to be flexible and capable of detecting subtle patterns within and between participant accounts without depending on prior theoretical constructs. Interviews were all transcribed word-for-word by the main researcher immediately after each interview to enhance accuracy and immersion into the data. The analysis was performed with NVivo version 10 software, which allowed for systematic coding and structuring of the emerging themes.

The analysis commenced with the principal researcher reading all the transcripts several times with a view to familiarizing herself with the data. This was then supplemented by line-by-line open coding, where meaningful units of text were labeled with codes that naturally arose out of the content. Subsequently, these codes were examined and consolidated into larger categories, from which preliminary themes were derived.

The research team collectively reviewed these themes to guarantee coherence, clarity, and congruence with the data. Themes were also developed through several rounds of review to accurately reflect the collective experiences of the participants. Representative interview quotes were then chosen to demonstrate each theme.

To maximize trustworthiness and credibility, the analysis was performed cooperatively by the principal investigator and two co-investigators with qualitative research backgrounds in health education. The group participated in frequent peer debriefing discussions to resolve coding discrepancies, confirm theme development, and enhance analysis depth. The analysis was carried out in a private, secure location at the university to ensure confidentiality and concentration. To further ensure validity, member checking was completed with three participants, who reviewed and agreed that the interpreted themes accurately represented their lived experiences. An audit trail was kept throughout the process, detailing all of the coding decisions, theme development, and analytical thinking. The principal researcher also kept a reflexive journal to recognize and control for assumptions and biases that might affect data interpretation.

Together, these approaches ensured that the analytical process was systematic, transparent, and credible, accurately reflecting the diverse experiences of dental students undergoing the curriculum shift in the post-COVID-19 era.

Results

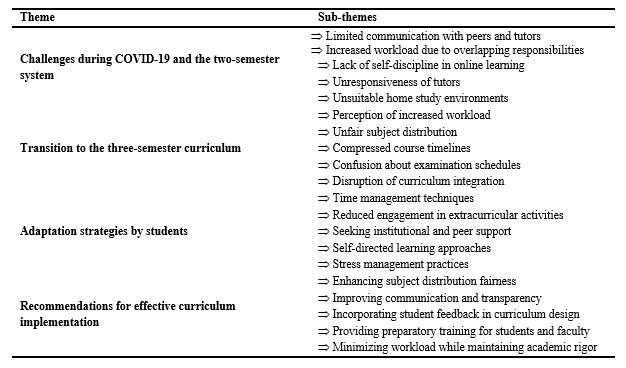

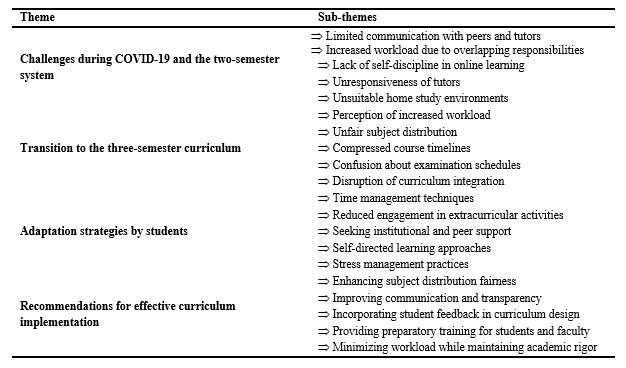

Thematic analysis of the interviews has been completed, and the identified themes are presented in Table 2. The following sections discuss the emergence of these themes from the interviews:

Table 2. Theme and sub-themes of the interview analysis

Theme 1—Challenges during COVID-19

1.1—Limited communication with peers and tutors

There is no doubt that the pandemic has presented numerous challenges for people worldwide, particularly resulting in significant changes to the global educational system. During the interviews, students expressed that they faced considerable struggles during this time, as their

studies were greatly affected. For instance, one student, referred to as P5, stated:

“It was a stressful situation for us as students because we were unable to manage our time for studying. Moreover, dental skills cannot be learned virtually, which posed an additional risk to our education."

1.2—Increased workload due to overlapping responsibilities

Eight students who were living with their families reported that their workload increased during the pandemic, even though they were not attending university.

These students felt additional pressure to contribute to household chores while staying at home. is evident in the response from P7, who stated:

"The study load and other workload increased for me during the pandemic as my mother expected me to help in the kitchen too while being at home."

1.3—Lack of self-discipline in online learning

The pandemic also introduced a distance learning platform for dental students. As they shifted to online learning, many reported a lack of communication with peers and minimal interaction with teachers. This sentiment is echoed in the response from P1, who stated:

"While learning online, there have been questions in my mind that could only be answered through practical explanation while interacting with the teacher."

1.4—Unresponsiveness of tutors

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the shift into online learning, which made significant gaps in communication between students and tutors. Many students noted unresponsiveness from their tutors that increased frustration and confusion in students. In contrast, traditional in-person learning does not have such barriers, where real-time questions can be responded to. As P3 reported:

"There were many times I reached out with questions via email or during virtual office hours, but I either received delayed responses or none at all. This made it difficult to clarify concepts and stay on track with the coursework."

1.5—Unsuitable home study environments

The online learning system during the pandemic posed many challenges for the students, as their home environment did not allow them to focus on studies. Many students faced distractions from their family members, lack of study space, and the constant noise from TV disrupted their concentration. As P9 shared:

"Studying at home was extremely challenging. There was constant noise from the TV, and I had to share a room with my siblings, who were also attending online classes. It was hard to focus on my studies or complete assignments on time.

Theme 2—Transition to the three-semester curriculum

2.1—Perception of increased workload

When the dental college at Taibah University implemented a three-semester system after two years of the pandemic, it presented numerous challenges for students who were accustomed to the traditional two-semester approach. Many students perceived this change as an increase in their academic workload, as illustrated by P3's comment:

"The two-semester system was much better, but the introduction of the three-semester system has made it hard for us to handle the study load and complete each study requirement at the time."

2.2—Unfair subject distribution

Most of the students suggested that time management was the most prominent issue in dealing with the new curriculum, as it introduced more quizzes and assignments than the past curriculum. Six students expressed concerns about the unequal distribution of subjects across the three semesters, which added significant stress for them. For example, P2 stated:

"I am unable to understand the subject distribution, as one semester includes all the subjects, while the other two are balanced."

2.3—Compressed course timelines

Many students were worried about the increased workload that the new curriculum imposed, particularly because challenging subjects required more time for practice. They felt that the shorter semesters were insufficient for thoroughly engaging with difficult topics. As P8 expressed:

"It has given us little time to learn and practice the compressed courses."

2.4—Confusion about examination schedules

Students are experiencing confusion when it comes to selecting an academic study plan, as this new curriculum presents numerous challenges and requires them to manage an increased workload. P10, when asked about exam details, shared:

"I have become much more confused with this new curriculum because the exam dates are too unclear. I don't understand when the exams will start or end, and I'm also unsure about the vacation schedule."

2.5—Disruption of curriculum integration

During the interviews, the reactions of two students appeared somewhat confused, as they did not fully grasp the rationale behind the introduction of the three-semester system.

These students viewed it as an irrelevant change, believing it did not demonstrate any significant progress toward the goals of Vision 2030. P6 commented:

"I cannot understand the connection between the three-semester system and the country's Vision 2030 goals. It seems like a confusing link that doesn't make sense."

Theme 3—Adaptation strategies by students

3.1—Time management techniques

Many students have been coping with the new system by putting in extra effort toward their studies, as the revised curriculum has more demanding requirements. When asked about the new study methods they adopted for this curriculum, P8 responded:

"This curriculum requires more study time on short notice, so I am learning to cover more subjects in a limited period."

3.2—Reduced engagement in extracurricular activities

The introduction of the new curriculum was unpredictable for students; however, many had no choice but to adapt, as it was a requirement. Their adaptation strategies were commendable, as P2 remarked:

"The new curriculum of the three-semester system has increased the burden on us, and to manage this, I have had to cut back on my extracurricular activities, including sports."

3.3—Seeking Institutional and Peer Support

Although face-to-face interactions resumed, it was the intensified academic calendar and increased workload that propelled most students to seek help both from the institution and their peer group. Peer networks were necessary to manage the curriculum demands. As P6 claimed:

"After the pandemic, even though we were back on campus, the three-semester system brought challenges. Study groups with my peers became essential to keep up with the pace, especially since the institution didn’t always clarify how the new system worked."

3.4—Self-directed learning approaches

The compact schedule left little time for guided learning, forcing students to take greater responsibility for various aspects of their education, such as identifying knowledge gaps and managing their study routines. P7 shared:

"I realized that I couldn't rely solely on lectures and needed to create my own study plans. I started using online resources like videos and articles to supplement what we learned in class."

Sub-theme 3.5—Stress management practices

This situation increased student stress levels, highlighting the need for effective strategies to manage stress and maintain academic performance. In response, some students engaged in physical activities and mindfulness practices and developed time management skills, among other techniques, to cope with the pressures of the new semester system. As P9 noted:

"I started exercising regularly and practicing mindfulness to keep my stress in It helped me stay focused and calm during exams."

Theme 4—Recommendations for effective curriculum implementation

4.1—Enhancing subject distribution fairness

When students were asked for their suggestions on what the system should implement to improve the situation, P5 proposed:

"With proper dialogue with students in dentistry, the sequence of subjects being followed should be changed."

4.2—Improving communication and transparency

Students also noted that the introduction of the three-semester system occurred without adequate communication. P1 suggested that:

"Before rolling out major curriculum changes, host informational sessions (either in person or virtually) where students can learn about the upcoming changes, ask questions, and express concerns. These sessions should include detailed explanations of the new system’s goals, structure, and expected outcomes."

4.3—Incorporating student feedback in curriculum design

P6 from the interview suggested that:

"If the curriculum had been introduced under different circumstances or with better management of study distribution, it would have received a much more positive response."

4.4—Providing preparatory training for students and faculty

Since the students were accustomed to the traditional two-semester system, P4 suggested that for the introduction of the three-semester system: "The university should provide proper training sessions for the faculty and students to cope with the new semester system and provide strategies to manage studies."

4.5—Minimizing workload while maintaining academic rigor

P8 also suggested that: "The workload in the three-semester system should be reduced by reducing the number of quizzes so that students have more time for preparing for final exams."

Discussion

This research surveyed dental students at Taibah University, a government institution under the Saudi Ministry of Education, during their transition from a two-semester to a three-semester learning system following the COVID-19 pandemic. It was determined using thematic analysis that students were encountering multidimensional adversity because of this dual disruption to teaching and the very structure of school. These results add to a better understanding of the impact on students in clinically intensive programs like dentistry caused by curriculum restructuring, particularly under crisis situations. The outbreak of COVID-19 led to a sudden shift towards online learning, derailing traditional pedagogical approaches. The shift from a two-semester to a three-semester program entailed redistribution of previous course materials into shorter periods of studies, not the introduction of additional courses. The shift condensed theory and clinical courses into more concentrated timeframes, impacting students' workload and study planning. The programs in the three-semester program comprised theoretical and clinical aspects. Students made particular reference to the difficulty of finishing clinical training on shortened schedules, particularly in areas like oral surgery and prosthodontics. Students in this research reported challenges in adjusting to learning spaces with minimal face-to-face interaction and practical clinical training. Most students reported that the lack of direct instruction from teachers was especially prejudicial to acquiring hands-on skills. In accordance with Tartavulea et al., it was noted that the abrupt change in learning style during the pandemic caused acute stress among healthcare students [11]. Similarly, Pavlíková et al. reported that dental and medical students incurred academic setbacks due to decreased clinical exposure and excessive dependence on theoretical teaching [12, 13]. The study participants also indicated psychological burdens due to learning in disorganized home settings. In some cases, household chores interfered with students' academic concentration, echoing Reimers' findings that students in health disciplines often bore an unjust burden during remote learning at home [14]. A primary concern expressed by interviewees was the incompatibility of dental education with online learning formats. This observation aligns with Oliveira et al., who found that dental students trained during the pandemic experienced a decrease in skill acquisition compared to previous cohorts [15]. Before the implementation of the three-semester system, students were already familiar with the conventional two-semester system that facilitated a predictable learning pace and regimented clinical rotations. This prior familiarity allowed the students to manage their learning workload more effectively during the early stages of the pandemic. As a few participants explained, this organization, though challenging when delivered remotely due to the technological limitations, remained feasible due to their previous familiarity with it.

The findings of the study are in accord with Alwadei et al., which mentioned that semester planning consistency alleviated some losses in learning amid COVID-19 in Saudi dental schools [16, 17]. Similarly, Nabayra and Tambong stressed that predictability in semester systems was an essential aspect of student satisfaction and scholarly performance amidst crisis-driven transitions [18]. Students perceived the introduction of the three-semester curriculum as badly timed and badly managed. Respondents described restructuring as worsening their study burden, curtailing their capacity to understand clinical information, and causing confusion about course timing and exams. This is consistent with the critique provided by Allmnakrah and Evers, who cautioned that top-down education reforms in Saudi Arabia, if carried out without the engagement of stakeholders, tend to lead to academic stress and student disengagement [19, 20]. One of the important issues brought up by students was the unequal balance of subjects within semesters. For instance, learners commented that one semester would be packed with challenging courses, while the others seemed less rigorous, thus complicating academic planning. Further, the truncated timelines within the three-semester framework left students with limited space for in-depth learning, reworking, or engagement in extracurricular activities, all important considerations for sustaining well-rounded clinical education. This confusion among students regarding the justification for this adjustment also resonates with general reservations in the literature regarding policy transparency. Although the reform was embedded within more general Vision 2030 education targets, students were not effectively informed about its applicability to their learning outcomes, especially in clinical programs. Soliman et al. also indicated that Saudi medical college students were dissatisfied with post-pandemic structural adjustment, noting ambiguous advantages and ineffective administrative coordination [21, 22].

Despite these challenges, students exhibited significant resilience through the implementation of self-directed learning approaches, including the utilization of digital materials, peer study groups, and digital scheduling tools to organize their workload. These adjustment strategies are supported by Abdelsalam et al., who noted that Saudi dental students increased their reliance on peer networks and independent study techniques during the disruptions caused by COVID-19 [23]. Such resilience must not be mistaken for a substitute for institutional accountability.

Participants repeatedly named lack of communication, orientation, and faculty training as impediments to effective adaptation. Crimmins et al. emphasize the importance of adequately preparing both students and faculty for the introduction of new curricula, focusing on training concerning new systems, expectations, and methods of delivery [24]. In their absence, well-designed reforms are bound to fail.

It should be noted that Taibah University, being a public institution under the Ministry of Education, functions within centralized systems that constrain its curricular flexibility. In contrast to private institutions or those institutions under other ministries (i.e., Health), its margin for flexibility in curriculum transitions is reduced by national imperatives. This research highlights the necessity for institutions such as Taibah to implement participatory approaches to curriculum planning that engage students and teachers, particularly when enacting large-scale structural reforms.

While national education reforms under Vision 2030 seek to improve academic effectiveness and synchronize programs with labor market needs, evidence from this study indicates that need to be discipline specific. In practice-oriented disciplines like dentistry, where experiential learning and cognitive overload are key issues, success in reforms relies not only on national goal congruence but also on contextual viability and academic preparedness.

This study indicates an acute disconnect between student reality and policy intention. While adopting a three-semester model may ultimately support long-term institutional goals, implementing this change during a global crisis has disproportionately affected students' learning momentum, psychological well-being, and skill acquisition. As Saudi Arabia pursues its educational reform under Vision 2030, there needs to be more focus on inclusive planning, support structures tailored to specific disciplines, and curriculum strategies specific to disciplines to guarantee that reforms produce the desired impact without undermining students' learning and development.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the experience of dental students at Taibah University, a government university falling under the Ministry of Education, as it transitioned from a two-semester to a three-semester system launched during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research revealed academic and psychological burdens on students, particularly in the clinical domain, where the demanding schedule and unclear course structure exacerbated the stress already induced by the pandemic. While the study offers valuable student-centered insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, particularly the exclusion of administrative and faculty perspectives, as well as its focus on a single institution. Consequently, the findings must be construed as exploratory, providing a foundation for more general investigations with a diverse array of stakeholders. For future transformation, it is essential that curriculum reorganization, particularly for healthcare courses, be complemented by open planning, equal academic pressures, and sufficient support systems. Institutions must engage students and teachers in the planning and execution of reforms to guarantee alignment with educational objectives and reduce stress during times of systemic change.

Ethical considerations

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured through giving each participant a pseudonym and by keeping the audio recordings and transcripts secure.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

This manuscript acknowledges the utilization of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools strictly in accordance with established ethical principles and academic guidelines. AI was employed solely to assist with language refinement, idea organization, and technical editing, while the core intellectual content, analysis, and conclusions presented remain the sole work of the author(s). All efforts were made to ensure originality, accuracy, and integrity, avoiding any misuse of AI-generated content or academic misconduct.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the students of the College of Dentistry at Taibah University for their valuable participation and willingness to share their experiences during the interviews. We also extend our appreciation to the faculty members and administrative staff who supported this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

ETN was responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study, data collection through semi-structured interviews, data analysis using thematic analysis, and interpretation of the findings. The author also wrote and revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Data availability statement

The data underlying the research findings can be accessed or obtained with a request from the corresponding author.

Background & Objective: The background of this research study involves past studies that highlight the struggle of students during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study outlines the challenges faced by dental students during the Covid-19 pandemic and highlights the struggles of dental students at Taibah University in Saudi Arabia regarding the implementation of a new curriculum that includes a three-semester system. Additionally, it explores the students' perspectives on the abrupt curriculum changes and the strategies they developed to adapt to these adjustments.

Materials & Methods: The methodology used in this study involved thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with ten students from the dental college at the university.

Results: The findings of this study showed that most of the dental students of Taibah University were not satisfied with the introduction of the new curriculum system.

Conclusion: The study recommends that any curriculum changes should be communicated effectively with both teachers and students to ensure that the new curriculum aligns with student needs. Additionally, both students and teachers should receive proper training in the use of new technologies to enhance education and better equip them to address future challenges.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on higher education systems globally, and universities were forced to quickly respond by making a transition from face-to-face teaching to remote and hybrid learning models [1]. These transitions were made to provide continuity of education in a period of crisis and were experienced across all fields, including clinical ones like dentistry [2]. In addition to the immediate transition to online education, some schools implemented more significant changes to their class schedules in an effort to mitigate educational loss and enhance system effectiveness [3].

At Taibah University in Saudi Arabia, the Faculty of Dentistry underwent a fundamental reorganization of its academic year, shifting from a traditional two-semester system to a three-semester format [4]. This transition was part of a broader national restructuring aligned with Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030, which aims to modernize and optimize educational institutions to meet new societal and workforce demands [5]. The change did not involve altering the curriculum itself; rather, it focused on restructuring and presenting the existing coursework in a more condensed and accelerated academic schedule [6].

This research does not refer to curriculum change in the traditional definition of altering learning outcomes, course content, or pedagogic strategies.

Rather, it explores a curricular framework shift, namely the reconstruction of the academic year into three semesters, and the instructional, psychological, and logistical hurdles that it caused dental students amid and following the pandemic. The differentiation is central to comprehending the emphasis and contribution of the research.

The need for this study is rooted in the paucity of previous research into students' experiences with such curricular structural changes. Most previous studies tackle remote learning challenges amidst COVID-19 but fail to consider the long-term effects of academic restructuring on clinical education programs [7- 9]. Given the demanding nature of dental education, where theoretical knowledge must be balanced with clinical practice, the transition to a three-semester model represents a significant change. This shift has potential implications for student performance, stress levels, and academic progress.

Hence, the aim of this research is to find out the experiences of dental students of Taibah University in going through this transition. The research seeks to record their perceptions regarding workload, modifications in clinical and theoretical training, psychological effects, and how they coped with the adjustments. The study seeks to answer the question: How did dental students at Taibah University experience and respond to the transition from a two-semester to a three-semester academic system during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This research utilized a qualitative descriptive approach through semi-structured interviews to investigate the experiences of dental students at Taibah University as they moved from a two-semester to a three-semester academic system within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of this approach was to allow in-depth personal views and subjective meanings of the restructuring of the academic environment, specifically concerning workload, stress, and coping mechanisms.

Participants and sampling

The research was carried out at the Taibah University College of Dentistry, a Saudi Arabian public university that is linked to the Ministry of Education.

The implementation of the curriculum reform into the three-semester system was carried out in accordance with national reforms outlined in Saudi Vision 2030. During the pandemic, the faculty employed Microsoft Teams and Blackboard platforms for communication and online learning. Nonetheless, some students complained that technical and communicative constraints hindered their capacity to interact effectively with instructors.

The purposive sampling method was applied when recruiting the students who had used both the two-semester and three-semester processes.

Ten students were selected to ensure a diverse representation of academic levels and genders. The participants were 6 females and 4 males, all in the 3rd or 4th year of their program of study in dentistry. These years were selected because this group of students had worked through preclinical training, were actively working on clinical and theoretical components of the curriculum, and, therefore, were appropriate informants for this study.

The study did not classify students by academic strength because of privacy concerns. Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the 10 participants who experienced both the two-semester and three-semester systems.

Table 1. Participant characteristics table

Data collection methods

Interviews were done in a secluded area, either face-to-face or through secure video conferencing tools based on student preference and accessibility. The interviews took anywhere from 30 to 45 minutes. The research team created an interview guide, which contained open-ended questions to elicit the views of the students regarding the three-semester system, how it affected their academic and clinical education, their well-being, and the support structures they utilized. Probing techniques to obtain more elaborate responses were employed. All the interviews were done by the author, who is a qualitative researcher trained and experienced in dental education research, and were audio-recorded with informed consent of the participants. Interviews were held in English.

Data analysis

The information gathered from the semi-structured interviews was coded and analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase inductive model outlined by Braun and Clarke, as discussed in a previous study [10]. The technique was selected because it was found to be flexible and capable of detecting subtle patterns within and between participant accounts without depending on prior theoretical constructs. Interviews were all transcribed word-for-word by the main researcher immediately after each interview to enhance accuracy and immersion into the data. The analysis was performed with NVivo version 10 software, which allowed for systematic coding and structuring of the emerging themes.

The analysis commenced with the principal researcher reading all the transcripts several times with a view to familiarizing herself with the data. This was then supplemented by line-by-line open coding, where meaningful units of text were labeled with codes that naturally arose out of the content. Subsequently, these codes were examined and consolidated into larger categories, from which preliminary themes were derived.

The research team collectively reviewed these themes to guarantee coherence, clarity, and congruence with the data. Themes were also developed through several rounds of review to accurately reflect the collective experiences of the participants. Representative interview quotes were then chosen to demonstrate each theme.

To maximize trustworthiness and credibility, the analysis was performed cooperatively by the principal investigator and two co-investigators with qualitative research backgrounds in health education. The group participated in frequent peer debriefing discussions to resolve coding discrepancies, confirm theme development, and enhance analysis depth. The analysis was carried out in a private, secure location at the university to ensure confidentiality and concentration. To further ensure validity, member checking was completed with three participants, who reviewed and agreed that the interpreted themes accurately represented their lived experiences. An audit trail was kept throughout the process, detailing all of the coding decisions, theme development, and analytical thinking. The principal researcher also kept a reflexive journal to recognize and control for assumptions and biases that might affect data interpretation.

Together, these approaches ensured that the analytical process was systematic, transparent, and credible, accurately reflecting the diverse experiences of dental students undergoing the curriculum shift in the post-COVID-19 era.

Results

Thematic analysis of the interviews has been completed, and the identified themes are presented in Table 2. The following sections discuss the emergence of these themes from the interviews:

Table 2. Theme and sub-themes of the interview analysis

Theme 1—Challenges during COVID-19

1.1—Limited communication with peers and tutors

There is no doubt that the pandemic has presented numerous challenges for people worldwide, particularly resulting in significant changes to the global educational system. During the interviews, students expressed that they faced considerable struggles during this time, as their

studies were greatly affected. For instance, one student, referred to as P5, stated:

“It was a stressful situation for us as students because we were unable to manage our time for studying. Moreover, dental skills cannot be learned virtually, which posed an additional risk to our education."

1.2—Increased workload due to overlapping responsibilities

Eight students who were living with their families reported that their workload increased during the pandemic, even though they were not attending university.

These students felt additional pressure to contribute to household chores while staying at home. is evident in the response from P7, who stated:

"The study load and other workload increased for me during the pandemic as my mother expected me to help in the kitchen too while being at home."

1.3—Lack of self-discipline in online learning

The pandemic also introduced a distance learning platform for dental students. As they shifted to online learning, many reported a lack of communication with peers and minimal interaction with teachers. This sentiment is echoed in the response from P1, who stated:

"While learning online, there have been questions in my mind that could only be answered through practical explanation while interacting with the teacher."

1.4—Unresponsiveness of tutors

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the shift into online learning, which made significant gaps in communication between students and tutors. Many students noted unresponsiveness from their tutors that increased frustration and confusion in students. In contrast, traditional in-person learning does not have such barriers, where real-time questions can be responded to. As P3 reported:

"There were many times I reached out with questions via email or during virtual office hours, but I either received delayed responses or none at all. This made it difficult to clarify concepts and stay on track with the coursework."

1.5—Unsuitable home study environments

The online learning system during the pandemic posed many challenges for the students, as their home environment did not allow them to focus on studies. Many students faced distractions from their family members, lack of study space, and the constant noise from TV disrupted their concentration. As P9 shared:

"Studying at home was extremely challenging. There was constant noise from the TV, and I had to share a room with my siblings, who were also attending online classes. It was hard to focus on my studies or complete assignments on time.

Theme 2—Transition to the three-semester curriculum

2.1—Perception of increased workload

When the dental college at Taibah University implemented a three-semester system after two years of the pandemic, it presented numerous challenges for students who were accustomed to the traditional two-semester approach. Many students perceived this change as an increase in their academic workload, as illustrated by P3's comment:

"The two-semester system was much better, but the introduction of the three-semester system has made it hard for us to handle the study load and complete each study requirement at the time."

2.2—Unfair subject distribution

Most of the students suggested that time management was the most prominent issue in dealing with the new curriculum, as it introduced more quizzes and assignments than the past curriculum. Six students expressed concerns about the unequal distribution of subjects across the three semesters, which added significant stress for them. For example, P2 stated:

"I am unable to understand the subject distribution, as one semester includes all the subjects, while the other two are balanced."

2.3—Compressed course timelines

Many students were worried about the increased workload that the new curriculum imposed, particularly because challenging subjects required more time for practice. They felt that the shorter semesters were insufficient for thoroughly engaging with difficult topics. As P8 expressed:

"It has given us little time to learn and practice the compressed courses."

2.4—Confusion about examination schedules

Students are experiencing confusion when it comes to selecting an academic study plan, as this new curriculum presents numerous challenges and requires them to manage an increased workload. P10, when asked about exam details, shared:

"I have become much more confused with this new curriculum because the exam dates are too unclear. I don't understand when the exams will start or end, and I'm also unsure about the vacation schedule."

2.5—Disruption of curriculum integration

During the interviews, the reactions of two students appeared somewhat confused, as they did not fully grasp the rationale behind the introduction of the three-semester system.

These students viewed it as an irrelevant change, believing it did not demonstrate any significant progress toward the goals of Vision 2030. P6 commented:

"I cannot understand the connection between the three-semester system and the country's Vision 2030 goals. It seems like a confusing link that doesn't make sense."

Theme 3—Adaptation strategies by students

3.1—Time management techniques

Many students have been coping with the new system by putting in extra effort toward their studies, as the revised curriculum has more demanding requirements. When asked about the new study methods they adopted for this curriculum, P8 responded:

"This curriculum requires more study time on short notice, so I am learning to cover more subjects in a limited period."

3.2—Reduced engagement in extracurricular activities

The introduction of the new curriculum was unpredictable for students; however, many had no choice but to adapt, as it was a requirement. Their adaptation strategies were commendable, as P2 remarked:

"The new curriculum of the three-semester system has increased the burden on us, and to manage this, I have had to cut back on my extracurricular activities, including sports."

3.3—Seeking Institutional and Peer Support

Although face-to-face interactions resumed, it was the intensified academic calendar and increased workload that propelled most students to seek help both from the institution and their peer group. Peer networks were necessary to manage the curriculum demands. As P6 claimed:

"After the pandemic, even though we were back on campus, the three-semester system brought challenges. Study groups with my peers became essential to keep up with the pace, especially since the institution didn’t always clarify how the new system worked."

3.4—Self-directed learning approaches

The compact schedule left little time for guided learning, forcing students to take greater responsibility for various aspects of their education, such as identifying knowledge gaps and managing their study routines. P7 shared:

"I realized that I couldn't rely solely on lectures and needed to create my own study plans. I started using online resources like videos and articles to supplement what we learned in class."

Sub-theme 3.5—Stress management practices

This situation increased student stress levels, highlighting the need for effective strategies to manage stress and maintain academic performance. In response, some students engaged in physical activities and mindfulness practices and developed time management skills, among other techniques, to cope with the pressures of the new semester system. As P9 noted:

"I started exercising regularly and practicing mindfulness to keep my stress in It helped me stay focused and calm during exams."

Theme 4—Recommendations for effective curriculum implementation

4.1—Enhancing subject distribution fairness

When students were asked for their suggestions on what the system should implement to improve the situation, P5 proposed:

"With proper dialogue with students in dentistry, the sequence of subjects being followed should be changed."

4.2—Improving communication and transparency

Students also noted that the introduction of the three-semester system occurred without adequate communication. P1 suggested that:

"Before rolling out major curriculum changes, host informational sessions (either in person or virtually) where students can learn about the upcoming changes, ask questions, and express concerns. These sessions should include detailed explanations of the new system’s goals, structure, and expected outcomes."

4.3—Incorporating student feedback in curriculum design

P6 from the interview suggested that:

"If the curriculum had been introduced under different circumstances or with better management of study distribution, it would have received a much more positive response."

4.4—Providing preparatory training for students and faculty

Since the students were accustomed to the traditional two-semester system, P4 suggested that for the introduction of the three-semester system: "The university should provide proper training sessions for the faculty and students to cope with the new semester system and provide strategies to manage studies."

4.5—Minimizing workload while maintaining academic rigor

P8 also suggested that: "The workload in the three-semester system should be reduced by reducing the number of quizzes so that students have more time for preparing for final exams."

Discussion

This research surveyed dental students at Taibah University, a government institution under the Saudi Ministry of Education, during their transition from a two-semester to a three-semester learning system following the COVID-19 pandemic. It was determined using thematic analysis that students were encountering multidimensional adversity because of this dual disruption to teaching and the very structure of school. These results add to a better understanding of the impact on students in clinically intensive programs like dentistry caused by curriculum restructuring, particularly under crisis situations. The outbreak of COVID-19 led to a sudden shift towards online learning, derailing traditional pedagogical approaches. The shift from a two-semester to a three-semester program entailed redistribution of previous course materials into shorter periods of studies, not the introduction of additional courses. The shift condensed theory and clinical courses into more concentrated timeframes, impacting students' workload and study planning. The programs in the three-semester program comprised theoretical and clinical aspects. Students made particular reference to the difficulty of finishing clinical training on shortened schedules, particularly in areas like oral surgery and prosthodontics. Students in this research reported challenges in adjusting to learning spaces with minimal face-to-face interaction and practical clinical training. Most students reported that the lack of direct instruction from teachers was especially prejudicial to acquiring hands-on skills. In accordance with Tartavulea et al., it was noted that the abrupt change in learning style during the pandemic caused acute stress among healthcare students [11]. Similarly, Pavlíková et al. reported that dental and medical students incurred academic setbacks due to decreased clinical exposure and excessive dependence on theoretical teaching [12, 13]. The study participants also indicated psychological burdens due to learning in disorganized home settings. In some cases, household chores interfered with students' academic concentration, echoing Reimers' findings that students in health disciplines often bore an unjust burden during remote learning at home [14]. A primary concern expressed by interviewees was the incompatibility of dental education with online learning formats. This observation aligns with Oliveira et al., who found that dental students trained during the pandemic experienced a decrease in skill acquisition compared to previous cohorts [15]. Before the implementation of the three-semester system, students were already familiar with the conventional two-semester system that facilitated a predictable learning pace and regimented clinical rotations. This prior familiarity allowed the students to manage their learning workload more effectively during the early stages of the pandemic. As a few participants explained, this organization, though challenging when delivered remotely due to the technological limitations, remained feasible due to their previous familiarity with it.

The findings of the study are in accord with Alwadei et al., which mentioned that semester planning consistency alleviated some losses in learning amid COVID-19 in Saudi dental schools [16, 17]. Similarly, Nabayra and Tambong stressed that predictability in semester systems was an essential aspect of student satisfaction and scholarly performance amidst crisis-driven transitions [18]. Students perceived the introduction of the three-semester curriculum as badly timed and badly managed. Respondents described restructuring as worsening their study burden, curtailing their capacity to understand clinical information, and causing confusion about course timing and exams. This is consistent with the critique provided by Allmnakrah and Evers, who cautioned that top-down education reforms in Saudi Arabia, if carried out without the engagement of stakeholders, tend to lead to academic stress and student disengagement [19, 20]. One of the important issues brought up by students was the unequal balance of subjects within semesters. For instance, learners commented that one semester would be packed with challenging courses, while the others seemed less rigorous, thus complicating academic planning. Further, the truncated timelines within the three-semester framework left students with limited space for in-depth learning, reworking, or engagement in extracurricular activities, all important considerations for sustaining well-rounded clinical education. This confusion among students regarding the justification for this adjustment also resonates with general reservations in the literature regarding policy transparency. Although the reform was embedded within more general Vision 2030 education targets, students were not effectively informed about its applicability to their learning outcomes, especially in clinical programs. Soliman et al. also indicated that Saudi medical college students were dissatisfied with post-pandemic structural adjustment, noting ambiguous advantages and ineffective administrative coordination [21, 22].

Despite these challenges, students exhibited significant resilience through the implementation of self-directed learning approaches, including the utilization of digital materials, peer study groups, and digital scheduling tools to organize their workload. These adjustment strategies are supported by Abdelsalam et al., who noted that Saudi dental students increased their reliance on peer networks and independent study techniques during the disruptions caused by COVID-19 [23]. Such resilience must not be mistaken for a substitute for institutional accountability.

Participants repeatedly named lack of communication, orientation, and faculty training as impediments to effective adaptation. Crimmins et al. emphasize the importance of adequately preparing both students and faculty for the introduction of new curricula, focusing on training concerning new systems, expectations, and methods of delivery [24]. In their absence, well-designed reforms are bound to fail.

It should be noted that Taibah University, being a public institution under the Ministry of Education, functions within centralized systems that constrain its curricular flexibility. In contrast to private institutions or those institutions under other ministries (i.e., Health), its margin for flexibility in curriculum transitions is reduced by national imperatives. This research highlights the necessity for institutions such as Taibah to implement participatory approaches to curriculum planning that engage students and teachers, particularly when enacting large-scale structural reforms.

While national education reforms under Vision 2030 seek to improve academic effectiveness and synchronize programs with labor market needs, evidence from this study indicates that need to be discipline specific. In practice-oriented disciplines like dentistry, where experiential learning and cognitive overload are key issues, success in reforms relies not only on national goal congruence but also on contextual viability and academic preparedness.

This study indicates an acute disconnect between student reality and policy intention. While adopting a three-semester model may ultimately support long-term institutional goals, implementing this change during a global crisis has disproportionately affected students' learning momentum, psychological well-being, and skill acquisition. As Saudi Arabia pursues its educational reform under Vision 2030, there needs to be more focus on inclusive planning, support structures tailored to specific disciplines, and curriculum strategies specific to disciplines to guarantee that reforms produce the desired impact without undermining students' learning and development.

Conclusion

The present study investigated the experience of dental students at Taibah University, a government university falling under the Ministry of Education, as it transitioned from a two-semester to a three-semester system launched during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research revealed academic and psychological burdens on students, particularly in the clinical domain, where the demanding schedule and unclear course structure exacerbated the stress already induced by the pandemic. While the study offers valuable student-centered insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, particularly the exclusion of administrative and faculty perspectives, as well as its focus on a single institution. Consequently, the findings must be construed as exploratory, providing a foundation for more general investigations with a diverse array of stakeholders. For future transformation, it is essential that curriculum reorganization, particularly for healthcare courses, be complemented by open planning, equal academic pressures, and sufficient support systems. Institutions must engage students and teachers in the planning and execution of reforms to guarantee alignment with educational objectives and reduce stress during times of systemic change.

Ethical considerations

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured through giving each participant a pseudonym and by keeping the audio recordings and transcripts secure.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

This manuscript acknowledges the utilization of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools strictly in accordance with established ethical principles and academic guidelines. AI was employed solely to assist with language refinement, idea organization, and technical editing, while the core intellectual content, analysis, and conclusions presented remain the sole work of the author(s). All efforts were made to ensure originality, accuracy, and integrity, avoiding any misuse of AI-generated content or academic misconduct.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the students of the College of Dentistry at Taibah University for their valuable participation and willingness to share their experiences during the interviews. We also extend our appreciation to the faculty members and administrative staff who supported this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

ETN was responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study, data collection through semi-structured interviews, data analysis using thematic analysis, and interpretation of the findings. The author also wrote and revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Data availability statement

The data underlying the research findings can be accessed or obtained with a request from the corresponding author.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2024/12/2 | Accepted: 2025/08/12 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2024/12/2 | Accepted: 2025/08/12 | Published: 2025/10/1

References

1. Babbar M, Gupta T. Response of educational institutions to COVID-19 pandemic: an inter-country comparison. Policy Futures in Educ. 2022;20(4):469-491. [DOI:10.1177/14782103211021937] [PMID] []

2. T arkar P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system. Int J Adv Sci Technol. 2020;29(9):3812-3814.

3. Daniel SJ. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects. 2020;49(1):91-96. [DOI:10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3] [PMID] []

4. Izumi T, Sukhwani V, Surjan A, Shaw R. Managing and responding to pandemics in higher educational institutions: initial learning from COVID-19. Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ. 2021;12(1):51-66. [DOI:10.1108/IJDRBE-06-2020-0054]

5. Toquero CM. Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: the Philippine context. Pedagogical Res. 2020;5(4):em0063. [DOI:10.29333/pr/7947]

6. Ali W. Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Educ Stud. 2020;10(3):16-25. [DOI:10.5539/hes.v10n3p16]

7. Tanveer M, Bhaumik A, Hassan S, Haq IU. Covid-19 pandemic, outbreak educational sector and students online learning in Saudi Arabia. J Entrep Educ. 2020;23(3):1-14.

8. Alshaikh K, Maasher S, Bayazed A, Saleem F, Badri S, Fakieh B. Impact of COVID-19 on the educational process in Saudi Arabia: a technology-organization-environment framework. Sustainability. 2021;13(13):7103. [DOI:10.3390/su13137103]

9. Bahanshal DA, Khan I. Effect of COVID-19 on education in Saudi Arabia and e-learning strategies. Arab World Engl J Spec Issue CALL. 2021;7:1-9. [DOI:10.24093/awej/call7.25]

10. Fona C. Qualitative data analysis: using thematic analysis. In: Researching and Analysing Business. Routledge; 2023. p. 130-145. [DOI:10.4324/9781003107774-11]

11. Tartavulea CV, Albu CN, Albu N, Dieaconescu RI, Petre S. Online teaching practices and the effectiveness of the educational process in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020;22(55):920-936. [DOI:10.24818/EA/2020/55/920]

12. Pavlíková M, Sirotkin A, Králik R, Petrikovičová L, Martin JG. How to keep university active during COVID-19 pandemic: experience from Slovakia. Sustainability. 2021;13(18):10350. [DOI:10.3390/su131810350]

13. Ellis V, Steadman S, Mao Q. 'Come to a screeching halt': can change in teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic be seen as innovation? Eur J Teach Educ. 2020;43(4):559-572. [DOI:10.1080/02619768.2020.1821186]

14. Reimers FM. Learning from a pandemic. The impact of COVID-19 on education around the world. In: Primary and Secondary Education During Covid-19: Disruptions to Educational Opportunity During a Pandemic. 2022:1-37. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_1] []

15. Oliveira G, Grenha Teixeira J, Torres A, Morais C. An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Br J Educ Technol. 2021;52(4):1357-1376. [DOI:10.1111/bjet.13112] [PMID] []

16. Alwadei AH, Tekian AS, Brown BP, Alwadei FH, Park YS, Alwadei SH, et al. Effectiveness of an adaptive eLearning intervention on dental students' learning in comparison to traditional instruction. J Dent Educ. 2020;84(11):1294-1302. [DOI:10.1002/jdd.12312] [PMID]

17. Freire C, Ferradás MM, Regueiro B, Rodríguez S, Valle A, Núñez JC. Coping strategies and self-efficacy in university students: a person-centered approach. Front Psychol. 2020;11:841. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00841] [PMID] []

18. Nabayra JN, Tambong CR. Readiness level, satisfaction indicators, and overall satisfaction towards flexible learning through the lens of public university teacher education students. Int J Inf Educ Technol. 2023;13(8): 1230-41. [DOI:10.18178/ijiet.2023.13.8.1925]

19. Allmnakrah A, Evers C. The need for a fundamental shift in the Saudi education system: implementing the Saudi Arabian economic vision 2030. Res Educ. 106(1):22-40. [DOI:10.1177/0034523719851534]

20. Quamar MM. Education system in Saudi Arabia: of change and reforms. Singapore: Springer; 2020. [DOI:10.1007/978-981-15-9173-0]

21. Soliman M, Aldhaheri S, Neel KF. Experience from a medical college in Saudi Arabia on undergraduate curriculum management and delivery during COVID-19 pandemic. J Nat Sci Med. 2021;4(2):85-89. [DOI:10.4103/jnsm.jnsm_146_20]

22. Bataeineh M, Aga O. Integrating sustainability into higher education curricula: Saudi Vision 2030. Emerald Open Res. 2023;1(3):

https://doi.org/10.1108/EOR-03-2023-0014 [DOI:10.1108/EOR-03-2023-0014.]

23. Abdelsalam M, Rodriguez TE, Brallier L. Student and faculty satisfaction with their dental curriculum in a dental college in Saudi Arabia. Int J Dent. 2020;2020:6839717. [DOI:10.1155/2020/6839717] [PMID] []

24. Crimmins G, Lipton B, McIntyre J, de Villiers Scheepers M, English P. Creative industries curriculum design for living and leading amid uncertainty. In: Educational Leadership and Policy in a Time of Precarity. Routledge; 2023. p. 20-36. [DOI:10.4324/9781003451617-3]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |