Sat, Jan 31, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 1 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(1): 54-64 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 972424

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Heidari A, Yoosefee S, Adeli S, AhmariTehran H, Ardebili M, Heidari M. Facilitators and barriers of the integration of spirituality into medical education: A situation analysis. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (1) :54-64

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2266-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2266-en.html

Akram Heidari1  , Sadegh Yoosefee2

, Sadegh Yoosefee2  , SeyedHasan Adeli1

, SeyedHasan Adeli1  , Hoda AhmariTehran1

, Hoda AhmariTehran1  , Maryam Ardebili1

, Maryam Ardebili1  , Morteza Heidari *3

, Morteza Heidari *3

, Sadegh Yoosefee2

, Sadegh Yoosefee2  , SeyedHasan Adeli1

, SeyedHasan Adeli1  , Hoda AhmariTehran1

, Hoda AhmariTehran1  , Maryam Ardebili1

, Maryam Ardebili1  , Morteza Heidari *3

, Morteza Heidari *3

1- Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. Neuroscience Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

3- School of Health and Religion, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran ,mortezaheidari.mh@gmail.com

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. Neuroscience Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

3- School of Health and Religion, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 808 kb]

(772 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1496 Views)

Full-Text: (333 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Spirituality is regarded as an essential aspect of health, and therefore, it should be incorporated into medical education to foster a holistic understanding of health and to develop fully competent medical professionals. Despite the significance of incorporating spiritual issues into medical education, there has been limited research conducted on this topic in Iran. Various barriers have hindered the implementation of spiritually enriched medical education; however, there are also some factors that facilitate this process. This study attempted to explore the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education through a qualitative content analysis.

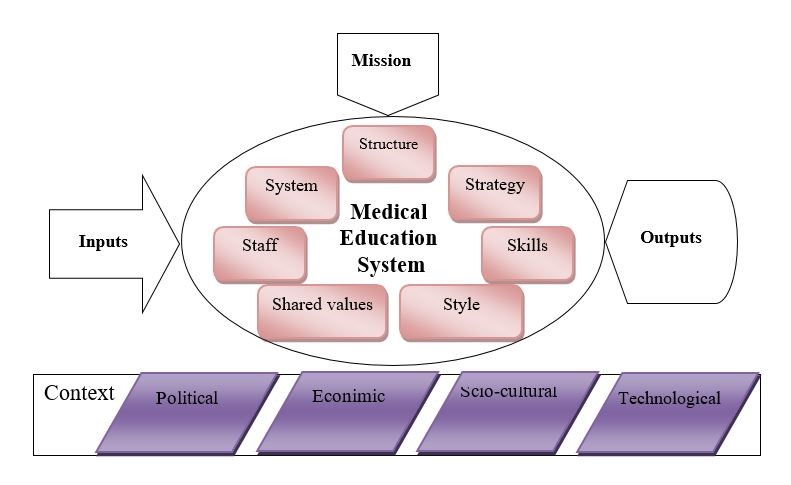

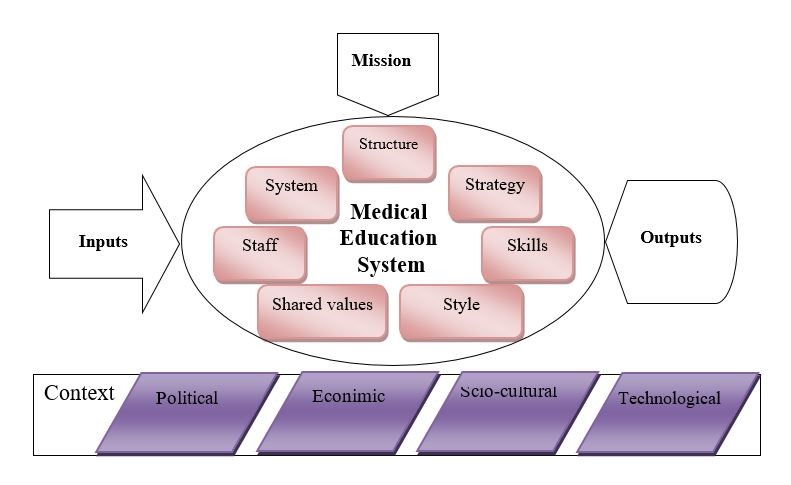

Materials & Methods: This was a situation analysis designed and conducted as a directed content analysis study. The data collected from interviews with medical education experts and the review of upstream documents were analyzed, revealing findings categorized as internal and external factors. Internal factors were categorized using the McKinsey 7S framework, which includes structure, systems, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values. Meanwhile, external factors were classified according to the PEST model, encompassing political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological aspects.

Results: The facilitators and barriers identified in this study encompassed a total of 100 concepts. We identified 27 internal and 16 external facilitators, while there were found 41 internal and 16 external barriers.

Conclusion: The findings of this study clarify the steps needed to uphold the goals and missions of medical education in the area of spiritual health. Overcoming the barriers while leveraging existing facilitators will be crucial for successfully incorporating spiritual health into Iranian medical education.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2. Internal facilitators and barriers to the integration of spirituality in medical education according to the McKinsey 7S framework

Table 3. External facilitators and barriers to the integration of spirituality in medical education according to the PEST model

Discussion

This study was an attempt to analyze the status of addressing the spiritual aspect of health in the Iranian medical education and explore its facilitators and barriers. The intrainstitutional facilitators and barriers to integrating spirituality into medical education were categorized using the McKinsey 7S framework, which includes structure, systems and processes, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values. Meanwhile, the extrainstitutional factors were classified according to the PEST model, encompassing political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological factors [28]. In other words, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats [29] affecting the integration of spiritual health in medical education, potentially or actually, were summed up. Medical education in Iran is interwoven with the healthcare system and thus, medical universities are multidimensional organizations. Mckinsey 7S framework focuses on the organization from the management perspective, emphasizing that the dysfunction of any subsystem could obstruct or hinder the achievement of organizational goals [30]. Furthermore, the success or failure of the organization is influenced, directly or indirectly, by the political, economic, social, and technological factors issues [31].

Despite a consensus on the importance of spirituality in health [32], the incompetence of healthcare providers has been a major reason for neglecting the spiritual aspect of

health. This incompetence largely stems from a lack of interprofessional education in this area, which in turn contributes to the reluctance of healthcare providers to integrate spiritual issues into their practice [33]. The integration of spirituality into medical education for

training more competent healthcare providers and consequently providing more respectful healthcare is achievable through interprofessional spiritual curricula [34]. This requires revisions in differen parts of education system as proposed by HosseiniMoghaddan and Hamidi who have considered the dependence of the future of interdisciplinarity in Iranian medical education to changes in relevant laws and regulations [35]. Spiritual care has been traditionally regarded as an option of palliative care for end-stage patients, but it is being recognized as a necessity for all patients and thus its integration into formal education is growing increasingly [36]. Nearly 60 percent of the participants of a study in Britain believe that a holistic approach in medical education necessitates addressing the spiritual aspect of health in educational programs [37]. This incompetence is mainly in the skills required for spiritual interventions in healthcare that is evidenced in this study as well as the existing literatue. Since, the underlying reasons for the lack of competence and little attention to interprofessional education in spiritual health could be sought in cultural, institutional, or curriculum-related factors, Improvement of the holistic medical education could lead to an improved healthcare provision for the patients [38]. Secularization as a result of modernization and enlightment discourse on the other hand, has influenced the separation of spirituality and health, but the renewed focus on the relationship between religion and health is a sign of a post-secular era even in the highly secular countries [39]. To conduct a balanced and all-round growth and development, we need adequate structure and system, that should be enhanced and this need is clearly perceived in providing the required structure. Management style and the strategies adopted by the managers have a determining role to develop and maintain this integration. It seems that more flexible and renewed curricula according to recent conditions are needed and should be developed [40]. Previous studies revealed that besides perceived clinical need, the right context of medical education for change was among the opportunities for the integration of spirituality into medical education [18]. Regarding the staff, the talented professionals including faculty members and researchers are valuable assets that could be helpful in the achievement of goals and the governing bodies could make the best of these assets through motivating, supporting, and providing the requirements. Individual activites by some pioneers and innovators has always been a strength [41]. Yet, the growing attrention to spiritual concerns and considerations in recent decades in Iran has been under the influence of the global trend rather than domestic innovations [42], although recent attempts and pursuits are in progress for the development of medical humanities along with the global trend in Iran [43, 44]. Thus, the presence of competent human resources particularly young activists in these fields from theory development to implementation and leadership provides optimism for the future that guarantees a self-sufficient development of the country accompanied with domestic cultural values that are essentially the constituents of the value and belief system of the society. When considering values as a cornerstone for integrating spiritual health into medical education, it is important to recognize that spirituality within the context of Islamic civilization is deeply rooted in the original and pure teachings of the Holy Qur'an, as well as those of the Holy Prophet and the Imams. This spirituality has its foundations in a clear understanding of Islamic theology, and the monotheistic worldview. Worldview is everyone's understanding and representation of the universe. Our emphasis on the Islamic worldview in spirituality is based on the fact that meaning of life as an aspect of spirituality and spiritual health and even the emotions are determined according to religious backgrounds [45]. In fact, every human being, even the seculars have their own worldview and this is the basis of their decisions and culture in general [46]. This differenitites people in terms of belief, behavior and decision making in different circumstances. While modern lifestyles require the coexistence of various worldviews, both religious and secular, the majority of our country's population identifies as Muslim. Therefore, spirituality grounded in this worldview can be considered a foundational intellectual framework across various sectors, including medical education. This has been experienced in Persian traditional medicine with the Islamic civilization around one thousand ago, where great scholars like Avicenna, Rhazes, Tabari, and Jorjani had developed a holistic approach to medicine [47]. The main point and the advantage of the Persian medicine in the Islamic civilization era was the integration of spirituality that was deeply embedded in medicine as an organic part and not merely as a supplement. Their outstanding effect on medicine was merging Iranian traditional medicine with the Islamic doctrine originated from Islamic sources [48] and it seems that this could take place again with modern considerations in present and future. This is in line with the idea of a community-oriented and socially accountable approach to medical education [49]. In this study, we tried to emphasize the multidimensional nature of medical universities in Iran and highlight the importance of addressing both organizational and contextual factors that could impact the success of integration of spirituality in medical education. Moreover, in the present study, we tried to provide practical solutions for integrating spirituality in medical education. But the study confronted limitations originating from the nature of qualitative research and the setting of the study. It seems that more studies are needed to precisely determine the solutions for different internal and external factors.

Conclusion

The integration of spiritual health into medical education in Iran encounters both facilitators and barriers. Facilitators are primarily rooted in the strong cultural background and religious orientation of the people, as well as in the governance that provides a supportive societal context for this integration. Additionally, growing recognition among medical professionals of the importance of holistic health, including spiritual aspects, contributes to a more receptive academic environment. However, several barriers hinder this integration process. These challenges include a lack of standardized curricula that address spiritual health, limited faculty expertise in teaching the spiritual aspects of healthcare, and potential resistance from individuals who view medicine solely through a biomedical lens. Overcoming these barriers while leveraging existing facilitators will be crucial for successfully incorporating spiritual health into Iranian medical education.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (code No. 972424). The researchers adhered to ethical principles and guidelines throughout the course of the study. To obtain informed consent from the participants, the objectives and overall framework of the study were clearly explained. All necessary measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of the data during the interview, data analysis, and preparing the report and the article manuscript. To avoid the potential biases of the researcher that might arise from cultural backgrounds, experiences, and values and their influence on the interpretation of the data, different strategies were considered. The triangulation of interviews along with document analysis was the main strategy and furthermore, bracketing was used to set aside preconceived notions and approach the data objectively. On the other hand, the diversity of the participants helped to avoid personal biases by the researcher.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

Artificial inteliigence was not utilized in preparation of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all scholars who kindly participated in this study and contributed to our findings.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed in initial design and conception of the study. MH conducted the interviews and their transcription. HAT, SY, SHA and MA were involved in the analysis and interpretation of th data. AH prepared the draft of the manuscript and all the authors read and approved its content to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR) with code No. 972424.

Data availability statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Background & Objective: Spirituality is regarded as an essential aspect of health, and therefore, it should be incorporated into medical education to foster a holistic understanding of health and to develop fully competent medical professionals. Despite the significance of incorporating spiritual issues into medical education, there has been limited research conducted on this topic in Iran. Various barriers have hindered the implementation of spiritually enriched medical education; however, there are also some factors that facilitate this process. This study attempted to explore the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education through a qualitative content analysis.

Materials & Methods: This was a situation analysis designed and conducted as a directed content analysis study. The data collected from interviews with medical education experts and the review of upstream documents were analyzed, revealing findings categorized as internal and external factors. Internal factors were categorized using the McKinsey 7S framework, which includes structure, systems, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values. Meanwhile, external factors were classified according to the PEST model, encompassing political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological aspects.

Results: The facilitators and barriers identified in this study encompassed a total of 100 concepts. We identified 27 internal and 16 external facilitators, while there were found 41 internal and 16 external barriers.

Conclusion: The findings of this study clarify the steps needed to uphold the goals and missions of medical education in the area of spiritual health. Overcoming the barriers while leveraging existing facilitators will be crucial for successfully incorporating spiritual health into Iranian medical education.

Introduction

The ultimate objective of medicine, along with the advancement of medical education and health sciences, is to promote the optimal well-being of individuals. Health, in its true and complete sense, encompasses various aspects of humanity through a holistic approach and cannot be fully attained unless the humanistic elements, including spirituality and the spiritual dimension of health, are taken into account [1]. Consequently, spiritual health has experienced a rebirth during the last half-century. Along with the emergence of spirituality in multiple social areas in the post-modern world and the particular attention to it in health, the spiritual dimension has been considered as the fourth to the physical, mental, and social dimensions declared in the World Health Organization's definition of health [2]. The significance of spirituality and spiritual health and its influence on the other dimensions is professed not only in religious outlooks but in secular paradigms as well [3]. Spirituality is interpreted in various ways within both religious and secular communities, and there is significant variation in how it is understood across different religious perspectives. Thus, everyone's spirituality is shaped or influenced by religious, sociocultural, historical, and personal backgrounds and experiences [4]. While spirituality may manifest in diverse ways, it appears to converge in its core meaning and primary components, which include aspects of humanity such as the search for meaning and purpose in life, transcendence, connection with communities, and the inner value system in relation to oneself, others (family, community, society), nature, and the significant or sacred [5, 6]. Despite the diversity of perspectives on spirituality across various cultures and healthcare systems, influenced by global variances in religious and spiritual beliefs, there appears to be a growing consensus on the importance of incorporating spirituality into healthcare [7-9]. The significance of spirituality in health lies in the fact that it exerts its effects on the overall well-being of human beings in different ways [10]. Spiritual health is closely related to mental health indicators like self-efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life, life satisfaction, and successful coping and adaptation [11]. On the other hand, insufficient spiritual health leads to emotional and behavioral disorders. Regarding the determining role of spiritual health on overall health, plenty of studies have been conducted and the issue is being accepted as an integral part of health research. Patients and their families are increasingly getting conscious of religious/ spiritual factors in health-threatening conditions, especially in end-of-life and terminal illnesses [12]. But, it is necessary to address the spiritual factors by the healthcare professionals in all fields of medical practice [13]. It is evident that spiritual interventions in healthcare require both knowledge and experience, which must be acquired and cultivated. The gap in the academic context of medical education is evident, and there is a strong need to integrate spirituality into the curriculum. To reach this end, healthcare professionals should be trained in their undergraduate, post-graduate, and continuing medical education to achieve the required competence [14].

American Association of Medical Colleges, the World Health Organization, and The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations have underscored the inclusion of spirituality in healthcare and medical education [15]. As a result of this need, more than 90 percent of medical schools in the United States and 59 percent in the United Kingdom have included a kind of training in the field of spirituality in their curriculum [16], and it is being developed in Brazil and other countries [17]. Nevertheless, various challenges have impeded the development of spiritual health curricula and their integration in Iranian medical schools' programs. Curriculum overload, clinicians' unwillingness or resistance due to unfelt need or lack of knowledge, and considering spirituality as a private concern and the idea that spiritually could be learned only through hidden curriculum, are among the obstacles [18]. Nonetheless, Iranian upstream documents such as the "Iran's Twenty-Year Vision Document," "The Islamic University Document," "Iranian National Scientific Map," "Iranian Scientific Map of Health," "the Announcement of the Second Phase of the Islamic Revolution," and the "Health Sector Major Policies" outline a future vision for Iranian higher education as a civilization developer, serving as an inspiration for Islamic countries, committed to the goals of the Islamic revolution, capable of nurturing elite scholars, and embodying the Iranian-Islamic lifestyle model. These documents provide a perspective to the construction of new Islamic civilization for which both education and health systems are of utmost importance [19]. Thus, highlighting the gap between national policy visions and the existing status in different areas could provide the scene to actively engage in their implementation. In the area of spiritual health education in medical universities, it seems that the perspectives, though well-designed, have not been actively addressed in real situations, particularly in universities of medical sciences. Therefore, the integration of spirituality in the health system and accordingly medical education could provide the ground for training the healthcare professionals in accordance with the cultural and religious background of people.This study was conducted with a qualitative approach through scrutinizing Iranian upstream documents and meanwhile interviewing medical education experts to explore from their point of view the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality into medical education. The internal barrirers and facilitators were organized in McKinsey 7S (structure, system, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values) framework and the external factors were classified with the PEST (political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological) model.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This situational analysis study was carried out using qualitative content analysis. The study was based on data obtained from interviews with medical education experts and a thorough examination of national upstream documents. A directed content analysis method was employed, utilizing the ‘structured’ approach developed by Elo and Kyngas (2008) out of various approaches to directed content analysis. In the structured approach, a categorization matrix serves as the framework for data collection and analysis, guiding the review and coding of the data [20]. Directed content analysis begins with a framework or findings from previous studies, which serve as a guide for developing initial codes [21]. We used McKinsey 7-S framework for internal factors and PEST model for external factors as the existing frameworks of our analysis.

The McKinsey 7-S framework, developed by Waterman, Peters, and Phillips in 1980, comprises seven elements: Structure, Strategy, Systems, Style, Staff, Skills, and Shared Values. Strategy, structure, and system are referred to as hard S's, while shared values, style, staff, and skills are categorized as soft S elements. The elements are defined as follows:

The PEST model, on the other hand, consists of Political, Economic, Socio-cultural, and Technological factors. PEST is commonly used to give an overview of the different macro-environmental factors that are beyond the control of an organization [24]. PEST concept was developed and introduced in 1967 by Francis J. Aguilar in his book: “Scanning the business environment” [25].

American Association of Medical Colleges, the World Health Organization, and The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations have underscored the inclusion of spirituality in healthcare and medical education [15]. As a result of this need, more than 90 percent of medical schools in the United States and 59 percent in the United Kingdom have included a kind of training in the field of spirituality in their curriculum [16], and it is being developed in Brazil and other countries [17]. Nevertheless, various challenges have impeded the development of spiritual health curricula and their integration in Iranian medical schools' programs. Curriculum overload, clinicians' unwillingness or resistance due to unfelt need or lack of knowledge, and considering spirituality as a private concern and the idea that spiritually could be learned only through hidden curriculum, are among the obstacles [18]. Nonetheless, Iranian upstream documents such as the "Iran's Twenty-Year Vision Document," "The Islamic University Document," "Iranian National Scientific Map," "Iranian Scientific Map of Health," "the Announcement of the Second Phase of the Islamic Revolution," and the "Health Sector Major Policies" outline a future vision for Iranian higher education as a civilization developer, serving as an inspiration for Islamic countries, committed to the goals of the Islamic revolution, capable of nurturing elite scholars, and embodying the Iranian-Islamic lifestyle model. These documents provide a perspective to the construction of new Islamic civilization for which both education and health systems are of utmost importance [19]. Thus, highlighting the gap between national policy visions and the existing status in different areas could provide the scene to actively engage in their implementation. In the area of spiritual health education in medical universities, it seems that the perspectives, though well-designed, have not been actively addressed in real situations, particularly in universities of medical sciences. Therefore, the integration of spirituality in the health system and accordingly medical education could provide the ground for training the healthcare professionals in accordance with the cultural and religious background of people.This study was conducted with a qualitative approach through scrutinizing Iranian upstream documents and meanwhile interviewing medical education experts to explore from their point of view the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality into medical education. The internal barrirers and facilitators were organized in McKinsey 7S (structure, system, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values) framework and the external factors were classified with the PEST (political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological) model.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

This situational analysis study was carried out using qualitative content analysis. The study was based on data obtained from interviews with medical education experts and a thorough examination of national upstream documents. A directed content analysis method was employed, utilizing the ‘structured’ approach developed by Elo and Kyngas (2008) out of various approaches to directed content analysis. In the structured approach, a categorization matrix serves as the framework for data collection and analysis, guiding the review and coding of the data [20]. Directed content analysis begins with a framework or findings from previous studies, which serve as a guide for developing initial codes [21]. We used McKinsey 7-S framework for internal factors and PEST model for external factors as the existing frameworks of our analysis.

The McKinsey 7-S framework, developed by Waterman, Peters, and Phillips in 1980, comprises seven elements: Structure, Strategy, Systems, Style, Staff, Skills, and Shared Values. Strategy, structure, and system are referred to as hard S's, while shared values, style, staff, and skills are categorized as soft S elements. The elements are defined as follows:

- Structure is the way an organisation is organized and the way in which tasks are divided and coordinated.

- Strategy is the way an organization aims to improve its position in long-term with the least cost.

- Systems mean all formal and informal, short-term and long-term procedures of the organization.

- Style is the key managers' behavior for achieving the organisation’s goals.

- Staff refers to the personnel within the organization and their morale, attitude, motivation, and behavior.

- Skills are the core competencies and capabilities of the employees to fulfill their roles.

- Shared values or superordinate goals refer to the central beliefs, guiding an organization that go beyond the formal statements [22].

The PEST model, on the other hand, consists of Political, Economic, Socio-cultural, and Technological factors. PEST is commonly used to give an overview of the different macro-environmental factors that are beyond the control of an organization [24]. PEST concept was developed and introduced in 1967 by Francis J. Aguilar in his book: “Scanning the business environment” [25].

- Political factors include the political system of the country, regulations, policies, and decrees issued by the government.

- Economic factors include the country's economic structure, policies of the ruling party, and the economic trend of the society.

- Socio-cultural factors include the social environment in which the organization is located and on which it depend for survival, including education, cultural attitude, customs, beliefs, etc.

- Technological factors refer to the influence of science and technology on an organization and its innovations.

Figure 1. The overall framework of the internal and external context of medical education

Participants and sampling

Fifteen experts participated in the study and underwent in-depth semi-structured interviews. Theoretical saturation was achieved after 15 interviews. To enhance the credibility of the data, the inclusion criteria required participants to have a minimum of five years of experience as university instructors in medical education or research, along with published works relevant to the topic under study. We aimed to maximize participant diversity regarding gender, age, discipline, and affiliated university to ensure that a range of ideas and opinions were represented, thereby minimizing potential personal and professional biases as well as the influences of the cultural context of their respective cities.

Additionally, the key upstream government documents relevant to our study were examined and analyzed. These included Iran's "Twenty-Year Vision Document," "The Islamic University Document," "Iranian National Scientific Map," "Iranian Scientific Map of Health," "the Announcement of the Second Phase of the Islamic Revolution," and the "Health Sector Major Policies."

The inclusion criteria for the upstream documents focused on their national scope, issuance by high governing departments, and relevance to the medical education system in areas such as education, research, healthcare, and cultural issues within the system. This led to selection and inclusion of six upstream documents. The interview participants were included in the study on the basis of their previous works and the amount of the information they could provide. Most of the interviewees were identified and recognized by the researchers, while some participants were referred to the researchers by the interviewees themselves.

Tools/Instruments

We developed an interview guide according to the literature and the aims of the study. The interview guide was modified during the interview process on the basis of acquired data and the gap of knowledge that was required to be addressed.

Data collection methods

The upstream documents were reviewed by the research team members specifically looking for concepts related to spiritual health and its integration to healthcare and medical education. The concepts were written on an MS Word file and were analyzed. Interviews were held according to the participants' convenience in terms of time and place so that the interviews were done with the least inconvenience for them and the minimum interruptions as a result of their parallel work. All the interviews were done by one researcher to keep consistency and guide the interview direction to fill the gaps as far as possible. The interview process commenced with an opening question about the current status of spirituality in medical education, followed by probing and follow-up questions designed to maximize the effectiveness of each interview and gather as much information as possible. Each interview lasted 40 to 75 minutes and they were recorded with the permission and consent of the interviewees. After the completion of each interview, the data analysis began and continued to the end of the interviews. The data analysis was done using MS Word files for the

Data analysis

During data analysis, the transcribed text of interviews were read repeatedly and the meaning units were identified and the codes were extracted from them. The codes produced in this phase both from the documents and interviews underwent continuous comparisons, and similar codes were merged and the most expressive and appropriate codes that most exactly described the meaning were adopted. The researcher highlighted a word, phrase, sentence, or a paragraph as a meaning unit. Then, a code was attributed to this meaning unit. The codes emerging in the process of coding were stated as concept [26]. A concept is the representation of an idea being conveyed in a content under analysis [27]. In the next phase, the concepts were located in the matrix consisiting of seven elements of McKinsey framework and the four elements of the PEST model, each containing a column for facilitators and a column for barriers.

Results

The participants included educators from medical universities, encompassing medical doctors (internists, surgeons, forensic medicine experts, and community medicine experts), pharmacologists, epidemiologists, medical ethics experts, medical education specialists, nursing experts, as well as experts in religious studies and future studies. The interviewees worked in different universities of medical sciences in Iran and had relevant experiences and publications, especially in interdisciplinary fields. Other demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Fifteen experts participated in the study and underwent in-depth semi-structured interviews. Theoretical saturation was achieved after 15 interviews. To enhance the credibility of the data, the inclusion criteria required participants to have a minimum of five years of experience as university instructors in medical education or research, along with published works relevant to the topic under study. We aimed to maximize participant diversity regarding gender, age, discipline, and affiliated university to ensure that a range of ideas and opinions were represented, thereby minimizing potential personal and professional biases as well as the influences of the cultural context of their respective cities.

Additionally, the key upstream government documents relevant to our study were examined and analyzed. These included Iran's "Twenty-Year Vision Document," "The Islamic University Document," "Iranian National Scientific Map," "Iranian Scientific Map of Health," "the Announcement of the Second Phase of the Islamic Revolution," and the "Health Sector Major Policies."

The inclusion criteria for the upstream documents focused on their national scope, issuance by high governing departments, and relevance to the medical education system in areas such as education, research, healthcare, and cultural issues within the system. This led to selection and inclusion of six upstream documents. The interview participants were included in the study on the basis of their previous works and the amount of the information they could provide. Most of the interviewees were identified and recognized by the researchers, while some participants were referred to the researchers by the interviewees themselves.

Tools/Instruments

We developed an interview guide according to the literature and the aims of the study. The interview guide was modified during the interview process on the basis of acquired data and the gap of knowledge that was required to be addressed.

Data collection methods

The upstream documents were reviewed by the research team members specifically looking for concepts related to spiritual health and its integration to healthcare and medical education. The concepts were written on an MS Word file and were analyzed. Interviews were held according to the participants' convenience in terms of time and place so that the interviews were done with the least inconvenience for them and the minimum interruptions as a result of their parallel work. All the interviews were done by one researcher to keep consistency and guide the interview direction to fill the gaps as far as possible. The interview process commenced with an opening question about the current status of spirituality in medical education, followed by probing and follow-up questions designed to maximize the effectiveness of each interview and gather as much information as possible. Each interview lasted 40 to 75 minutes and they were recorded with the permission and consent of the interviewees. After the completion of each interview, the data analysis began and continued to the end of the interviews. The data analysis was done using MS Word files for the

Data analysis

During data analysis, the transcribed text of interviews were read repeatedly and the meaning units were identified and the codes were extracted from them. The codes produced in this phase both from the documents and interviews underwent continuous comparisons, and similar codes were merged and the most expressive and appropriate codes that most exactly described the meaning were adopted. The researcher highlighted a word, phrase, sentence, or a paragraph as a meaning unit. Then, a code was attributed to this meaning unit. The codes emerging in the process of coding were stated as concept [26]. A concept is the representation of an idea being conveyed in a content under analysis [27]. In the next phase, the concepts were located in the matrix consisiting of seven elements of McKinsey framework and the four elements of the PEST model, each containing a column for facilitators and a column for barriers.

Results

The participants included educators from medical universities, encompassing medical doctors (internists, surgeons, forensic medicine experts, and community medicine experts), pharmacologists, epidemiologists, medical ethics experts, medical education specialists, nursing experts, as well as experts in religious studies and future studies. The interviewees worked in different universities of medical sciences in Iran and had relevant experiences and publications, especially in interdisciplinary fields. Other demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

In addition, the upstream documents previously listed formed another source of data for this study. The data analysis involved continuous coding of the data, comparing the codes, merging similar codes, and eliminating duplicates. Finally, 100 concepts entered the structured content analysis and were designated in the

predetermined frameworks according to their relevance. Table 2 indicates the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education at the interinstitutional level. Table 3 indicates the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education from the extra-institutional viewpoint

predetermined frameworks according to their relevance. Table 2 indicates the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education at the interinstitutional level. Table 3 indicates the facilitators and barriers of integrating spirituality in medical education from the extra-institutional viewpoint

Table 2. Internal facilitators and barriers to the integration of spirituality in medical education according to the McKinsey 7S framework

Table 3. External facilitators and barriers to the integration of spirituality in medical education according to the PEST model

Discussion

This study was an attempt to analyze the status of addressing the spiritual aspect of health in the Iranian medical education and explore its facilitators and barriers. The intrainstitutional facilitators and barriers to integrating spirituality into medical education were categorized using the McKinsey 7S framework, which includes structure, systems and processes, strategies, skills, staff, style, and shared values. Meanwhile, the extrainstitutional factors were classified according to the PEST model, encompassing political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological factors [28]. In other words, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats [29] affecting the integration of spiritual health in medical education, potentially or actually, were summed up. Medical education in Iran is interwoven with the healthcare system and thus, medical universities are multidimensional organizations. Mckinsey 7S framework focuses on the organization from the management perspective, emphasizing that the dysfunction of any subsystem could obstruct or hinder the achievement of organizational goals [30]. Furthermore, the success or failure of the organization is influenced, directly or indirectly, by the political, economic, social, and technological factors issues [31].

Despite a consensus on the importance of spirituality in health [32], the incompetence of healthcare providers has been a major reason for neglecting the spiritual aspect of

health. This incompetence largely stems from a lack of interprofessional education in this area, which in turn contributes to the reluctance of healthcare providers to integrate spiritual issues into their practice [33]. The integration of spirituality into medical education for

training more competent healthcare providers and consequently providing more respectful healthcare is achievable through interprofessional spiritual curricula [34]. This requires revisions in differen parts of education system as proposed by HosseiniMoghaddan and Hamidi who have considered the dependence of the future of interdisciplinarity in Iranian medical education to changes in relevant laws and regulations [35]. Spiritual care has been traditionally regarded as an option of palliative care for end-stage patients, but it is being recognized as a necessity for all patients and thus its integration into formal education is growing increasingly [36]. Nearly 60 percent of the participants of a study in Britain believe that a holistic approach in medical education necessitates addressing the spiritual aspect of health in educational programs [37]. This incompetence is mainly in the skills required for spiritual interventions in healthcare that is evidenced in this study as well as the existing literatue. Since, the underlying reasons for the lack of competence and little attention to interprofessional education in spiritual health could be sought in cultural, institutional, or curriculum-related factors, Improvement of the holistic medical education could lead to an improved healthcare provision for the patients [38]. Secularization as a result of modernization and enlightment discourse on the other hand, has influenced the separation of spirituality and health, but the renewed focus on the relationship between religion and health is a sign of a post-secular era even in the highly secular countries [39]. To conduct a balanced and all-round growth and development, we need adequate structure and system, that should be enhanced and this need is clearly perceived in providing the required structure. Management style and the strategies adopted by the managers have a determining role to develop and maintain this integration. It seems that more flexible and renewed curricula according to recent conditions are needed and should be developed [40]. Previous studies revealed that besides perceived clinical need, the right context of medical education for change was among the opportunities for the integration of spirituality into medical education [18]. Regarding the staff, the talented professionals including faculty members and researchers are valuable assets that could be helpful in the achievement of goals and the governing bodies could make the best of these assets through motivating, supporting, and providing the requirements. Individual activites by some pioneers and innovators has always been a strength [41]. Yet, the growing attrention to spiritual concerns and considerations in recent decades in Iran has been under the influence of the global trend rather than domestic innovations [42], although recent attempts and pursuits are in progress for the development of medical humanities along with the global trend in Iran [43, 44]. Thus, the presence of competent human resources particularly young activists in these fields from theory development to implementation and leadership provides optimism for the future that guarantees a self-sufficient development of the country accompanied with domestic cultural values that are essentially the constituents of the value and belief system of the society. When considering values as a cornerstone for integrating spiritual health into medical education, it is important to recognize that spirituality within the context of Islamic civilization is deeply rooted in the original and pure teachings of the Holy Qur'an, as well as those of the Holy Prophet and the Imams. This spirituality has its foundations in a clear understanding of Islamic theology, and the monotheistic worldview. Worldview is everyone's understanding and representation of the universe. Our emphasis on the Islamic worldview in spirituality is based on the fact that meaning of life as an aspect of spirituality and spiritual health and even the emotions are determined according to religious backgrounds [45]. In fact, every human being, even the seculars have their own worldview and this is the basis of their decisions and culture in general [46]. This differenitites people in terms of belief, behavior and decision making in different circumstances. While modern lifestyles require the coexistence of various worldviews, both religious and secular, the majority of our country's population identifies as Muslim. Therefore, spirituality grounded in this worldview can be considered a foundational intellectual framework across various sectors, including medical education. This has been experienced in Persian traditional medicine with the Islamic civilization around one thousand ago, where great scholars like Avicenna, Rhazes, Tabari, and Jorjani had developed a holistic approach to medicine [47]. The main point and the advantage of the Persian medicine in the Islamic civilization era was the integration of spirituality that was deeply embedded in medicine as an organic part and not merely as a supplement. Their outstanding effect on medicine was merging Iranian traditional medicine with the Islamic doctrine originated from Islamic sources [48] and it seems that this could take place again with modern considerations in present and future. This is in line with the idea of a community-oriented and socially accountable approach to medical education [49]. In this study, we tried to emphasize the multidimensional nature of medical universities in Iran and highlight the importance of addressing both organizational and contextual factors that could impact the success of integration of spirituality in medical education. Moreover, in the present study, we tried to provide practical solutions for integrating spirituality in medical education. But the study confronted limitations originating from the nature of qualitative research and the setting of the study. It seems that more studies are needed to precisely determine the solutions for different internal and external factors.

Conclusion

The integration of spiritual health into medical education in Iran encounters both facilitators and barriers. Facilitators are primarily rooted in the strong cultural background and religious orientation of the people, as well as in the governance that provides a supportive societal context for this integration. Additionally, growing recognition among medical professionals of the importance of holistic health, including spiritual aspects, contributes to a more receptive academic environment. However, several barriers hinder this integration process. These challenges include a lack of standardized curricula that address spiritual health, limited faculty expertise in teaching the spiritual aspects of healthcare, and potential resistance from individuals who view medicine solely through a biomedical lens. Overcoming these barriers while leveraging existing facilitators will be crucial for successfully incorporating spiritual health into Iranian medical education.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (code No. 972424). The researchers adhered to ethical principles and guidelines throughout the course of the study. To obtain informed consent from the participants, the objectives and overall framework of the study were clearly explained. All necessary measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of the data during the interview, data analysis, and preparing the report and the article manuscript. To avoid the potential biases of the researcher that might arise from cultural backgrounds, experiences, and values and their influence on the interpretation of the data, different strategies were considered. The triangulation of interviews along with document analysis was the main strategy and furthermore, bracketing was used to set aside preconceived notions and approach the data objectively. On the other hand, the diversity of the participants helped to avoid personal biases by the researcher.

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

Artificial inteliigence was not utilized in preparation of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all scholars who kindly participated in this study and contributed to our findings.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed in initial design and conception of the study. MH conducted the interviews and their transcription. HAT, SY, SHA and MA were involved in the analysis and interpretation of th data. AH prepared the draft of the manuscript and all the authors read and approved its content to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR) with code No. 972424.

Data availability statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2024/09/1 | Accepted: 2025/02/5 | Published: 2025/04/14

Received: 2024/09/1 | Accepted: 2025/02/5 | Published: 2025/04/14

References

1. Wald HS, McFarland J, Markovina I. Medical humanities in medical education and practice. Medical Teacher. 2019;41(5):492-6. [DOI]

2. Dhar N, Chaturvedi SK, Nandan D. Spiritual health, the fourth dimension: a public health perspective. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 2013;2(1):3-5 [DOI]

3. Hvidt NC, Assing Hvidt E. Religiousness, spirituality and health in secular society: need for spiritual care in health care? Spirituality, Religiousness and Health: From Research to Clinical Practice. 2019:133-52. [DOI]

4. Murgia C, Notarnicola I, Caruso R, De Maria M, Rocco G, Stievano A. Spirituality and religious diversity in nursing: a scoping review. InHealthcare. 2022;10(9):1661. [DOI]

5. Murgia C, Notarnicola I, Rocco G, Stievano A. Spirituality in nursing: a concept analysis. Nursing Ethics. 2020;27(5):1327-43. [DOI]

6. Dubey P, Pathak AK, Sahu KK. Correlates of workplace spirituality on job satisfaction, leadership, organisational citizenship behaviour and organisational growth: a literature-based study from organisational perspective. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research. 2020;9(4):1493-502 [DOI]

7. Mthembu TG, Wegner L, Roman NV. Teaching spirituality and spiritual care in health sciences education: a systematic review. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences. 2016;22(41):1036-57. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025] [DOI]

8. Crozier D, Greene A, Schleicher M, Goldfarb J. Teaching spirituality to medical students: a systematic review. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. 2022;28(3):378-99 [DOI]

9. Wenham J, Best M, Kissane DW. Systematic review of medical education on spirituality. Internal Medicine Journal. 2021;51(11):1781-90. [DOI]

10. Koenig HG. Religion and medicine III: developing a theoretical model. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31(2):199-216. [DOI]

11. Darvishi A, Otaghi M, Mami S. The effectiveness of spiritual therapy on spiritual well-being, self-esteem and self-efficacy in patients on hemodialysis. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020;59(1):277-88. [DOI]

12. Ford DW, Downey L, Engelberg R, Back AL, Curtis JR. Discussing religion and spirituality is an advanced communication skill: an exploratory structural equation model of physician trainee self-ratings. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(1):63-70. [DOI]

13. Monroe MH, Bynum D, Susi B, et al. Primary care physician preferences regarding spiritual behavior in medical practice. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(22):2751-6 [DOI]

14. Whitley R. Religious competence as cultural competence. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(2):245-260 [DOI]

15. Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: the development of a field. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(1):10-16 [DOI]

16. Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG, Espinha DCM, de Oliveira LR, Leite JR, Koenig HG. Spirituality and health in the curricula of medical schools in Brazil. BMC Medical Education. 2012;12(1):78. [DOI]

17. Lucchetti G, de Araujo Almeida PO, Martin EZ, et al. The current status of “spirituality and health” teaching in Brazilian medical schools: a nationwide survey. BMC Medical Education. 2023;23(1):172. [DOI]

18. Memaryan N, Rassouli M, Nahardani SZ, Amiri P. Integration of spirituality in medical education in Iran: a qualitative exploration of requirements. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015(1):793085. [DOI]

19. Alipour Hafezi M. Expectations of upstream documents from the higher education system. Quarterly Journal of Research and Planning in Higher Education. 2024;30(2):1-15. [DOI]

20. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(1):107-15. [DOI]

21. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277-88. [DOI]

22. Waterman Jr RH, Peters TJ, Phillips JR. Structure is not organization. Business Horizons. 1980;23(3):14-26. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

23. Shelke T, Sidhu H, Parab V. Mckinsey 7s model: applicability and relevance in educational sector. General Management. 204. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

24. Wang L, Hou C. Analysis of macro environment and development countermeasures of the education industry based on the PEST model. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences. 2023;8(2):2755-64. [DOI]

25. Datta S, Kutzewski T. The conventional wisdom in strategy. InStrategic optionality: pathways through disruptive uncertainty 2023 Jan 19 (pp. 37-90). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [DOI]

26. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1758-72. [DOI]

27. Kleinheksel A, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, Wyatt TR. Demystifying content analysis. American journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2020;84(1):7113 [DOI]

28. Bismark O, Kofi O, Frank A, Eric H. Utilizing Mckinsey 7S model, SWOT analysis, PESTLE and balance scorecard to foster efficient implementation of organizational strategy. Evidence from the community hospital group-Ghana limited. International Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management. 2018;2(3):94-113. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

29. Helms MM, Nixon J. Exploring SWOT analysis–where are we now? A review of academic research from the last decade. Journal of Strategy and Management. 2010;3(3):215-51. [DOI]

30. Singh A. A study of role of McKinsey's 7S framework in achieving organizational excellence. Organization Development Journal. 2013;31(3):39. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

31. Walsh K, Bhagavatheeswaran L, Roma E. E-learning in healthcare professional education: an analysis of political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental (PESTLE) factors. MedEdPublish. 2019;8(97):97. [DOI]

32. Demir E. The evolution of spirituality, religion and health publications: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019;58(1):1-13 [DOI]

33. Baldacchino D. Spiritual care education of health care professionals. Religions; 2015;6(2):594-613. [DOI]

34. Puchalski CM, Ferrell B, Bauer RW. Interprofessional spiritual care education curriculum. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2024;67(5):e548-e9 [DOI]

35. Hoseini Moghadam M, Hamidi M. The future of interdisciplinarity in higher education: experiences of medical universities in Iran. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities. 2022;14(3):87-122. [DOI]

36. Bolhari J, DOUS AH, Mirzaee M. Spiritual approach in medical education and humanities. 2012. [Persian]. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

37. Harbinson MT, Bell D. How should teaching on whole person medicine, including spiritual issues, be delivered in the undergraduate medical curriculum in the United Kingdom? BMC Medical Education. 2015;15(1):1-13. [DOI]

38. Vermette D, Doolittle B. What educators can learn from the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of patient care: Time for holistic medical education. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2022;37(8):2062-6. [DOI]

39. Nissen RD, Andersen AH. Addressing religion in secular healthcare: existential communication and the post-secular negotiation. Religions. 2021;13(1):34. [DOI]

40. Tavakol M, Murphy R, Torabi S. Medical education in Iran: an exploration of some curriculum issues. Medical Education Online. 2006;11(1):4585. [DOI]

41. Malekpoor N, Abedi F, ArabZozani M, Farrokhfall K. A SWOT analysis of integrating humanities into medical sciences curricula. Future of Medical Education Journal. 2024;14(2). [DOI]

42. Zahedi F, Emami Razavi S, Larijani B. A two-decade review of medical ethics in Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2009;38(Suppl 1):40-6. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

43. Sadati AK, Lankarani KB, Falakodin Z, Zanganeh M. Analysis of strategies for integrating humanities with medical sciences in Iran from the perspective of humanities experts with convergence sciences approach. Journal of Medical Education and Development. 2020. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jan. 15, 2025]. [DOI]

44. Sadati AK, Lankarani KB, Falakodin Z. Modern mentality, domination, and the unequal field of knowledge, resources, and talent: challenges of the formation of medical humanities in Iran. Journal of Applied Sociology (1735-000X). 2021;32(3). [DOI]

45. Cohen AB, Keltner D, Rozin P. Different religions, different emotions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2004;27(6):734-5. [DOI]

46. Van der Kooij JC, de Ruyter DJ, Miedema S. “Worldview”: the meaning of the concept and the impact on religious education. Religious Education. 2013;108(2):210-28. [DOI]

47. Pasalar M. Persian medicine as a holistic therapeutic approach. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. 2021;18(2):159 [DOI]

48. Zeinalian M, Eshaghi M, Naji H, Marandi SMM, Sharbafchi MR, Asgary S. Iranian-Islamic traditional medicine: an ancient comprehensive personalized medicine. Advanced Biomedical Research. 2015;4(1):191. [DOI]

49. Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Academic Medicine. 2020 Dec 1;95(12):1817-22. [DOI]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |