Sun, Feb 1, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 1 (2025)

J Med Edu Dev 2025, 18(1): 76-86 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: DMIMS (DU)/IEC/2020-21/9060 dated 10.10.2020

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Agarwal P, Biswas D A. Reflection on the response of healthcare professionals to the COVID-19 pandemic-preclinical students identify what their profession is about. J Med Edu Dev 2025; 18 (1) :76-86

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2163-en.html

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-2163-en.html

1- Department of Physiology, Government Institute of Medical Sciences, Greater Noida 201310, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, India. , dr.preranaagarwal@gmail.com

2- Department of Physiology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education & Research (DU), Sawangi (Meghe) 442107, Wardha, Maharashtra, India

2- Department of Physiology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education & Research (DU), Sawangi (Meghe) 442107, Wardha, Maharashtra, India

Keywords: Health profession, medical professionalism, professional identity formation, reflective thinking, pandemic

Full-Text [PDF 927 kb]

(452 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1286 Views)

Full-Text: (172 Views)

Abstract

Background & Objective: Medical professionalism and identity formation are typically learned through hands-on medical training and practice. But during the early COVID–19 pandemic, medical students were displaced from campus. However, they could engage with the characteristics of the profession by critically observing the response of healthcare professionals to the COVID–19 pandemic through news, such other means. and personal experience. The purpose of this study was to explore if preclinical students could discern the core values of their profession in such unusual circumstances.

Materials & Methods: The qualitative study, content analysis based on the principles of grounded theory, was conducted from October 2020 – January 2021, among the preclinical students of a medical college in India. After an online sensitization, they were asked to write reflection notes. The reflection notes of all 28 respondents were analysed thematically using QDA Miner Lite 2.0.5.

Results: There were 28 respondents. An exhaustive number of 15 themes emerged from the analysis of their reflection notes that encompassed various aspects of the medical profession – ranging from good moral character attributes of a healthcare professional to hazards of the profession to the students taking pride in being associated with it. What is identified by a student as being important, may be expected to be learned better by them. Therefore, we may expect these students to have learned about the attributes of medical professionalism and identity formation, which they had identified through reflection, more meaningfully when they joined back

Conclusion: Even while off campus, students likely continued to learn about their profession. It is reasonable to expect they may gain a deep understanding of their profession upon resuming their training on campus.

Preclinical students, though shielded from direct hospital involvement to minimize exposure, witnessed the heroism of healthcare workers through media and personal experiences. This exposure likely influenced their professional identity, a concept that evolves through training and incorporates personal, professional, and social dimensions. Students absorb these aspects not only from explicit curricular teachings but also through the profession's implicit practices [6]. To explore the impact of the pandemic on professional identity formation [7] among preclinical students, we conducted a project assessing their perceptions of medical professionalism based on their observations of involvement of healthcare professionals during the pandemic. This analysis seeks to understand how students interpret the ideals of medical professionalism in the face of unprecedented challenges, thereby gaining insight into their evolving professional identity, shaped by both external role models and internal values [7]. This exploration is crucial for nurturing future physicians who embody the ethos of compassionate and dedicated healthcare delivery under all circumstances.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The qualitative study, content analysis based on the principles of grounded theory, was conducted from October 2020 – January 2021, during the lockdown period in the country when the students had been home and the teaching shifted to online mode, in the Department Physiology of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research (previously Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences) (Deemed to be University), Sawangi (Meghe), Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

Research Question

What have the preclinical students discerned about the medical profession concerning its core values by observing the role of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Research Team

Both the authors, both females, were teachers of the preclinical students who participated in the study. One author, Prerna Agarwal, has previously worked on qualitative research and took the lead on data collection and analysis. The study being conducted online, it is less likely that the students were forced to participate, ensuring a more voluntary and unbiased response rate. The online format likely provided students with a sense of anonymity and comfort, allowing them to express their genuine perceptions without fear of judgment or repercussions.

Participants and sampling

The study was carried out among the preclinical students, of MBBS batches 2019 and 2020, studying in professional years first, I and second, II, aged 17-21 years, after obtaining ethical clearance from the institute, vide letter no. DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2020-21/9060 dated 10/10/2020, and an informed consent of the participants was obtained. From among the respondents, it was decided to analyse as many reflection notes till no further new codes and themes were deduced.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

All the respondents were included in the study. However, any incomplete reflections and anyone not giving their consent to participate in the study were excluded.

Tools/Instruments

The data were collected using a Google Form shared on the WhatsApp groups of the students’ virtual classrooms.

Data collection method

A virtual meeting was conducted on the Zoom platform to brief the students about the purpose and expectations of the present study. The discussion focussed on the response of healthcare professionals towards the pandemic – Have you been reading newspapers and watching the television for news about the COVID-19 pandemic? Have you or any of your acquaintances had any personal experiences related to it? What have you come to know about how healthcare professionals are dealing with it? Did any particular news catch your attention? What do you understand about the medical profession from it? How do you relate yourself to it? To provide students with greater clarity, they were encouraged to share their diverse experiences and perspectives regarding the roles of healthcare professionals during the pandemic.

The students were then asked to write reflection notes on the same and share them through a Google Form. The google form contained a brief description about the context and clues to help the students in writing the narrative.

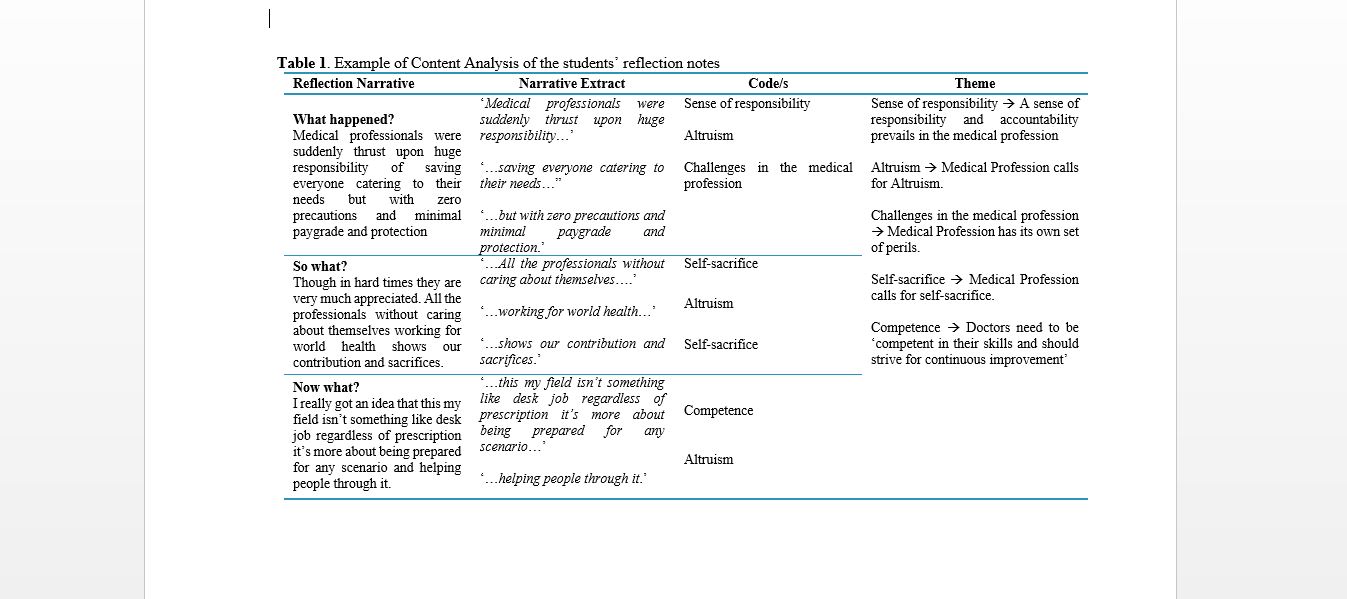

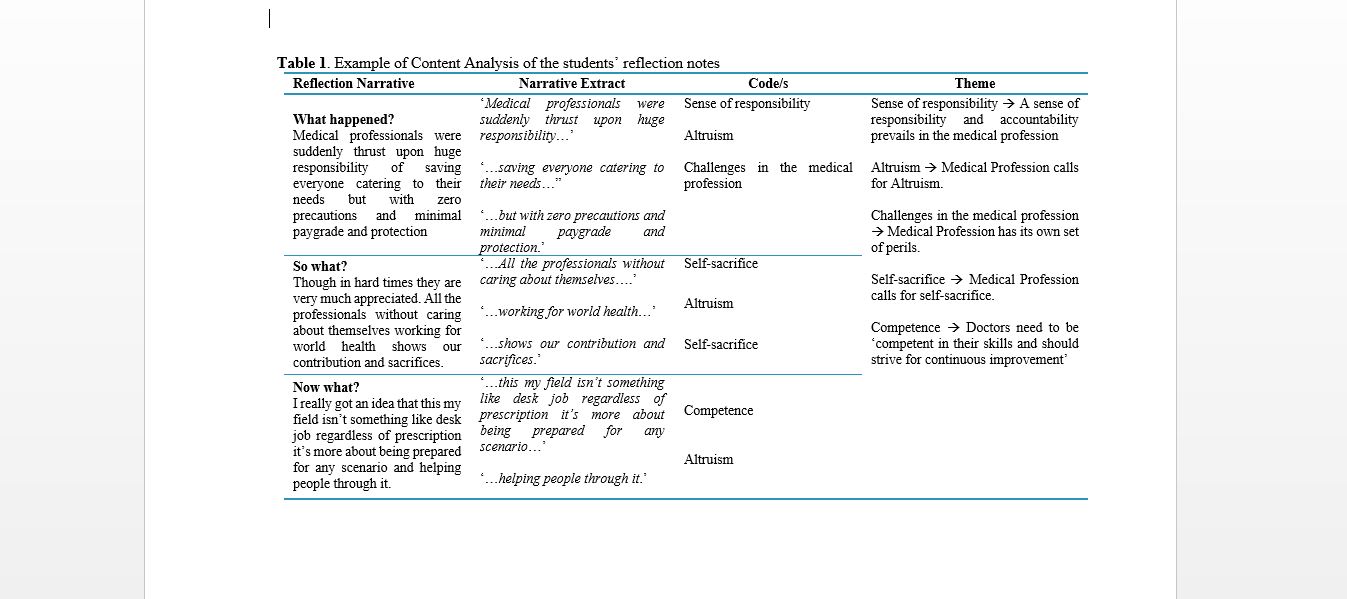

Data analysis

Both of us (authors), separately, analyzed all the reflection notes/essays thematically. We assigned codes to various segments of the data, exchanged notes, and derived themes from codes. We discussed the themes in the context of expectations from a healthcare professional and how students identified themselves with them. (Table 1 contains an example of how data analysis was done.)

The analysis was done using QDA Miner Lite 2.0.5.

Table 1. Example of Content Analysis of the students’ reflection notes

Reflexivity

Reflexivity was integral to our approach to ensure the reliability and depth of our thematic analysis. Author PA has previously authored a paper on medical professionalism and author DAB is a very senior professor in the institute. Both authors taught the preclinical students among whom the study was carried out. We engaged in regular discussions to critically examine our biases and preconceptions about medical professionalism and student reflections. Our collaborative reflexivity enabled us to navigate the complex narratives presented by the students, ensuring that our thematic derivation was exhaustive and consistent with the varied experiences and insights they shared.

Results

There were 28 respondents (Table 2) and we included reflection notes of all of them in the study for data analysis. The reflection notes of the students underscored their own empathy for healthcare professionals. They identified the challenges and hazards of the medical profession. They reflected a sense of pride in being associated with the profession. At the same time, the students also identified the sense of duty and service healthcare professionals have towards society. They showed an understanding of the requirements of dedication, competence, soft skills, empathy, team spirit, self-sacrifice, leadership skills, and hard work for the practice of the profession with ‘professionalism’. They

also identified the government as an important stakeholder in the healthcare profession. (See appendix). We identified codes pertaining to these characteristics and developed themes based on them. All these themes together identified the various attributes of medical professionalism and professional identity formation, in general [8].

Table 2. Demographic details of the respondents (ages 17 - 21 years)

None

Data availability statement

Upon a reasonable request, the corresponding author can provide the datasets analyzed in this study.

Supplementary

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1id-Mb30y88-3OXjYANDESAyzVRfda2pI/view?usp=sharing

Background & Objective: Medical professionalism and identity formation are typically learned through hands-on medical training and practice. But during the early COVID–19 pandemic, medical students were displaced from campus. However, they could engage with the characteristics of the profession by critically observing the response of healthcare professionals to the COVID–19 pandemic through news, such other means. and personal experience. The purpose of this study was to explore if preclinical students could discern the core values of their profession in such unusual circumstances.

Materials & Methods: The qualitative study, content analysis based on the principles of grounded theory, was conducted from October 2020 – January 2021, among the preclinical students of a medical college in India. After an online sensitization, they were asked to write reflection notes. The reflection notes of all 28 respondents were analysed thematically using QDA Miner Lite 2.0.5.

Results: There were 28 respondents. An exhaustive number of 15 themes emerged from the analysis of their reflection notes that encompassed various aspects of the medical profession – ranging from good moral character attributes of a healthcare professional to hazards of the profession to the students taking pride in being associated with it. What is identified by a student as being important, may be expected to be learned better by them. Therefore, we may expect these students to have learned about the attributes of medical professionalism and identity formation, which they had identified through reflection, more meaningfully when they joined back

Conclusion: Even while off campus, students likely continued to learn about their profession. It is reasonable to expect they may gain a deep understanding of their profession upon resuming their training on campus.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic [1], healthcare professionals demonstrated exemplary dedication in patient care, research, and administration, despite facing significant risks as frontline workers [2, 3]. Their efforts, which included ensuring equitable access to healthcare resources and providing care to patients with a highly contagious disease, highlighted the essence of medical professionalism [4]. This period of crisis offered profound insights into the challenges and values inherent in healthcare, prompting reflection on the responsibilities of medical professionals and influencing medical education and practice [5].Preclinical students, though shielded from direct hospital involvement to minimize exposure, witnessed the heroism of healthcare workers through media and personal experiences. This exposure likely influenced their professional identity, a concept that evolves through training and incorporates personal, professional, and social dimensions. Students absorb these aspects not only from explicit curricular teachings but also through the profession's implicit practices [6]. To explore the impact of the pandemic on professional identity formation [7] among preclinical students, we conducted a project assessing their perceptions of medical professionalism based on their observations of involvement of healthcare professionals during the pandemic. This analysis seeks to understand how students interpret the ideals of medical professionalism in the face of unprecedented challenges, thereby gaining insight into their evolving professional identity, shaped by both external role models and internal values [7]. This exploration is crucial for nurturing future physicians who embody the ethos of compassionate and dedicated healthcare delivery under all circumstances.

Materials & Methods

Design and setting(s)

The qualitative study, content analysis based on the principles of grounded theory, was conducted from October 2020 – January 2021, during the lockdown period in the country when the students had been home and the teaching shifted to online mode, in the Department Physiology of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research (previously Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences) (Deemed to be University), Sawangi (Meghe), Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

Research Question

What have the preclinical students discerned about the medical profession concerning its core values by observing the role of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Research Team

Both the authors, both females, were teachers of the preclinical students who participated in the study. One author, Prerna Agarwal, has previously worked on qualitative research and took the lead on data collection and analysis. The study being conducted online, it is less likely that the students were forced to participate, ensuring a more voluntary and unbiased response rate. The online format likely provided students with a sense of anonymity and comfort, allowing them to express their genuine perceptions without fear of judgment or repercussions.

Participants and sampling

The study was carried out among the preclinical students, of MBBS batches 2019 and 2020, studying in professional years first, I and second, II, aged 17-21 years, after obtaining ethical clearance from the institute, vide letter no. DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2020-21/9060 dated 10/10/2020, and an informed consent of the participants was obtained. From among the respondents, it was decided to analyse as many reflection notes till no further new codes and themes were deduced.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

All the respondents were included in the study. However, any incomplete reflections and anyone not giving their consent to participate in the study were excluded.

Tools/Instruments

The data were collected using a Google Form shared on the WhatsApp groups of the students’ virtual classrooms.

Data collection method

A virtual meeting was conducted on the Zoom platform to brief the students about the purpose and expectations of the present study. The discussion focussed on the response of healthcare professionals towards the pandemic – Have you been reading newspapers and watching the television for news about the COVID-19 pandemic? Have you or any of your acquaintances had any personal experiences related to it? What have you come to know about how healthcare professionals are dealing with it? Did any particular news catch your attention? What do you understand about the medical profession from it? How do you relate yourself to it? To provide students with greater clarity, they were encouraged to share their diverse experiences and perspectives regarding the roles of healthcare professionals during the pandemic.

The students were then asked to write reflection notes on the same and share them through a Google Form. The google form contained a brief description about the context and clues to help the students in writing the narrative.

Data analysis

Both of us (authors), separately, analyzed all the reflection notes/essays thematically. We assigned codes to various segments of the data, exchanged notes, and derived themes from codes. We discussed the themes in the context of expectations from a healthcare professional and how students identified themselves with them. (Table 1 contains an example of how data analysis was done.)

The analysis was done using QDA Miner Lite 2.0.5.

Table 1. Example of Content Analysis of the students’ reflection notes

Reflexivity

Reflexivity was integral to our approach to ensure the reliability and depth of our thematic analysis. Author PA has previously authored a paper on medical professionalism and author DAB is a very senior professor in the institute. Both authors taught the preclinical students among whom the study was carried out. We engaged in regular discussions to critically examine our biases and preconceptions about medical professionalism and student reflections. Our collaborative reflexivity enabled us to navigate the complex narratives presented by the students, ensuring that our thematic derivation was exhaustive and consistent with the varied experiences and insights they shared.

Results

There were 28 respondents (Table 2) and we included reflection notes of all of them in the study for data analysis. The reflection notes of the students underscored their own empathy for healthcare professionals. They identified the challenges and hazards of the medical profession. They reflected a sense of pride in being associated with the profession. At the same time, the students also identified the sense of duty and service healthcare professionals have towards society. They showed an understanding of the requirements of dedication, competence, soft skills, empathy, team spirit, self-sacrifice, leadership skills, and hard work for the practice of the profession with ‘professionalism’. They

also identified the government as an important stakeholder in the healthcare profession. (See appendix). We identified codes pertaining to these characteristics and developed themes based on them. All these themes together identified the various attributes of medical professionalism and professional identity formation, in general [8].

Table 2. Demographic details of the respondents (ages 17 - 21 years)

Theme 1. Medical Profession calls for Altruism.

Students quoted various instances as to how the doctors disregarded their own interests to work for the larger benefit of the people, and how they risked their own lives for treating patients. Respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student observed that,

“...When the staff came for collecting samples, people had different, some were cooperative and some were not. But then too, not keeping this in mind, these people did take all the samples, some gave swab samples and some took rapid antigen test. This shows that the medical professionals involved gave their best efforts they didn't discriminate between people … even after violence, non-cooperation from people, they didn't back down.”

Another student, a second professional year male student (Respondent no. 14) expressed, “… medical profession is the only profession where the professionals are still doing their job without much changes in there working pattern, OPD still are full with verities of patient where some understand the importance of current scenario but many don't and as a doctor you ignore those things and indulge yourself in treatment of others.”

Some students clearly stated that the medical profession is all about ‘helping others’ (Respondent no. 12, a male student of first professional year).

And in turn, some students acknowledged that the same inspired them ‘to do their best in helping people in need’ (Respondent no. 7, a first professional year female student).

Theme 2. Medical Professionals should have ‘good communication and other soft skills.’

Students mentioned that doctors need to have good communication and other soft skills while dealing with patients and their relatives/ caretakers. They stated how the same helps in establishing trust and understanding between them, and avoid conflict. A first professional year female student (Respondent no. 3) observed that

“….Proper counselling of family members of COVID-19 patient is being done by the doctors which is very important….”

Another first professional year female student (Respondent no. 28) thought that, “…effective communication amongst doctor and patient also the patient’s family need to be properly informed about the condition of the patient….”

Another first professional year female student noted (Respondent no. 04) that “….Majority of doctors find themselves struggling to choose right words when it comes to communicating with the kins of the patients. A lot of violence could be avoided by rightful exchange of words.”

A first professional year male student expressed (Respondent no. 27) that “…I learned that we need to first go to the patient then talk in a good manner, then take the permission asking him/her to diagnose or test etc.”

They mentioned that they will be “Working towards improving personal communication skills; Understanding the importance of establishing a good doctor patient relationship; Being an effective and responsible spokesperson for the medical community…” (Respondent no.5, a first professional year female student) , and that “.I would try to establish an understanding between me and person (patient)” (Respondent no. 24, a first professional year male student).

Theme 3. Doctors need to be ‘competent in their skills and should strive for continuous improvement’.

Students pointed out the need for being sound in knowledge and application, need for research in the field and having a scientific temperament. They vowed to inculcate the necessary skills in themselves. One first professional-year female student (Respondent no. 4) expressed that,

“Below are the following things that the current situation has made me realise: Development of a scientific temperament at an undergraduate level and constantly trying to adapt the same in day-to-day life…...”

“The importance of research has been brought up by this pandemic” was observed by respondent no. 9, a first professional year female student.

Another first profession year female student, (Respondent no. 16) stated that “Doctors have not only work on the treatment part but also the research part to get the right vaccine and to cure this virus from roots.”

A first professional year male student (Respondent no. 12) said that “In my future practice I will try to make the best use of my knowledge.”

Theme 4. Doctors ought to be ‘empathetic’ towards their patients.

Students put forth the importance of empathy for the patients and their care takers, and their own commitment for developing the same in their own behaviour.

“…Proper counselling of family members of COVID-19 patient is been done by the doctors which is very important. Not only by medical treatment but emotional support and empathy is also given by doctors,” was expressed by the first professional year female student (Respondent no.3).

“….since in the covid ward only the patient is allowed to stay the family member are always in stress and panic to know about the situation of the patient and is always curious to know about the recovery status of patient. So here comes the role of a doctor to inform about the situation of the patient and the treatment been given to them. This helps to keep hope and faith on the doctors. As they feel that their family member is in good hands,” was observed by the respondent no. 28, a first professional year female student.

“…and make a good relationship of empathy and respect for my patients,” was stated by respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student.

Likewise, respondent no. 24, a first professional year male student stated that, “...I would try to establish an understanding between me and person…”

Theme 5. Doctors should uphold ‘integrity of their character’ at all times.

Some students could identify that doctors should be virtuous in their character. They should be honest, dedicated and should not discriminate.

Respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student stated that, “…I believe that whoever is a part of the healthcare system should be dedicated and honest to their work only then can we defeat such disasters….”

Respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student observed that “…didn't discriminate between people…”

“People believe what doctors say. It is this trust which we have to keep strong as we, the medical professionals are the only sources of hope for the people and that’s the most important thing we should have in our minds…”, was expressed by respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student.

Theme 6. A sense of responsibility and accountability prevails in the medical profession.

Students understood the responsibility doctors bear on their shoulders. They could recognise their being accountable for the well-being of their patients and healthcare needs of the society in general. They said they would conduct themselves in an appropriate manner.

“…doctors have a great responsibility on their shoulders in such times...” noted respondent no. 10, a first professional year female student.

“…because it's their duty…” said respondent no. 7, another first professional year female student.

“…this profession is not for experimentation but a planned right action and decision has to be taken at right time. One mistake and we could lose the patient's life. This pandemic is a lesson…” said respondent no. 16, a first professional year female student. She also expressed that, “I am very inspired by the medical professionals during pandemic. It has raised a greater sense of responsibility within me towards the society.”

Another first professional year female student, respondent no. 4, stated that she would practice medicine “...keeping in mind how my actions could potentially harbour a feeling of distrust among general population.”

Theme 7. Medical profession is a ‘team work’.

Students cited many instances where they identified doctors/ healthcare professionals working as a team, and cooperating with each other. One first professional year female student, respondent no. 10, noted that, “….doctors who are although not working in the covid hospitals, but still, they are spreading awareness and asking people to wear masks and maintain hand hygiene. Not only this, the groups that have been formed by the administration that has a doctor with them…”

Another first professional year male student, respondent no 12, noted that, “…. It’s not only about the doctor but the credit goes to the entire team of 12 people who assisted the doctor and played different roles in the lab.”

Similarly, respondent no 5, another first professional year female student, observed that, “…they are really working very hard for us ........they work together as a group.”

Theme 8. Doctors should be able to ‘lead and guide’.

Some students mentioned that doctors should be able to assume leadership roles:

In this context, respondent no. 4, a first professional year female student expressed, “….I have realized the importance of supporting leadership qualities as a part of medical education…”

Theme 9. Doctors serve the community and patients ‘sense of service and duty’.

Students identified serving the community as the duty of healthcare professionals, including themselves as students. Respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student observed, “…the medical professionals and other people associated in any way with treating and serving the people….” Similarly, respondent no. 7, another first professional year female student also identified the word ’duty’, saying, “…are doing this because it's their duty.”Another respondent, no. 8, a first professional year female student, also used the words ‘serve’ and ‘duty’ while expressing, “…. Medical students are adept at many clinical roles. Allowing them to serve…. Should be allowed to fulfill their duties as such.”

Theme 10. Medical Profession involves a lot of ‘hard work’.

Students clearly pointed out the hard work that doctors put in:

“…physicians and health care professionals for their hard work, thoughtfulness, and commitment during this challenging time,” said respondent no.8, a first professional year female student. Respondent no. 5, a first professional year female student, also used the phrase ‘hard work’, “….they are really working very hard for us…”

Respondent no. 21, a first professional year male student observed, “…I have seen doctors, nurses working in double digit hours in PPE for the well-being of diseased people.” Similarly, respondent no. 27, also a first professional year male student noted,

“...I observed that doctors are working round the clock, they are not having proper food at time, Doctors are moving with covid patients all the time. They also have a family but they are ready to serve the patients in this pandemic situation. As, this disease being a highly contagious one doctors need to put on PPE kit all the time, I cannot express how they suffocate...”

Yet another respondent, no. 28, a first professional year female student observed, “…medical professionals have been overworked.”

Theme 11. Medical Profession calls for self-sacrifice.

Students also recognized the self-sacrifice involved in the practice of health care.

“Medical professionals were suddenly thrust upon huge responsibility of saving everyone catering to their needs but with zero precautions and minimal paygrade and protection,” and, “… all the professionals without caring about themselves working for world health shows our contribution and sacrifices,” said respondent no. 2, a first professional year female student to emphasise that doctors compromise their own needs. She also felt that, “The medical professionals are doing their best to help people, protecting them, staying away from their family to keep them safe as well.”

Respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student said doctors risked their won lives for patients’ sake, “...The COVID- 19 Pandemic situation is very difficult for everyone especially the medical professionals and other people associated in any way with treating and serving the people as they are risking their own lives, staying away from their own families for days and months and are stepping forward to help the society without thinking anything of their own good.”

Similarly, respondent no. 26, a first professional year male student also felt “Doctors trying hard to save lives by keeping their (own) life at stake.”

Theme 12. Medical Profession has its own set of perils.

Students identified many situations involving hazards, challenges to the healthcare professionals themselves, and how doctors put their duty ahead of their own interests. They also highlighted the lacunae in safety, and protection of healthcare professionals, and even lack of adequate acknowledgement of their contribution. Respondent no 3, a first professional year female student observed doctors contracting the disease from patients, “…In some cases, doctors are also being infected with COVID-19 during treatment of patients….”

In her expression,“…how the doctors are disrespected, even have to face some physical harms by the people in the society whom they serve….” respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student, highlighted assaults, out of fear, or misinformation, on doctors.

Respondent no. 15, another first professional year female, highlighted over work, need for rest, and abuse of doctors in the context, “….The doctors need rest. Patients need to take that into consideration. After working 24×7 this is not what they expect. I have seen patients getting extremely abusive towards the doctor for not treating their patient even though the doctor was himself not well…”

Similarly, respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student, also identified aggressions against doctors, “…, they acted as first line of defence during this pandemic, and even after violence, non-cooperation from people, they didn't back down, and I don't think anyone else could have done it in this way….”

Likewise, respondent no. 24, also a first professional year male student stated “…People were afraid of virus and they saw medical professionals as a connection to virus. During pandemic I went to photograph shop. He was not welcoming for me in apron and asked me to leave so there was some fear against medical professionals which can be harmful sometimes.”

Respondent no. 4, a first professional year female student identified ‘impairment of human rights of doctors’ in her expression,“….Further the improper implementation of laws has impaired the human rights of doctors leading to multiple protests.” Respondent no. 28, a first professional year female student identified ‘stigma’ being associated with medical personnel and their families, “...medical professionals have been overworked, general population usually tries to avoid them, medical professional families not treated well and stigmatized from the potential fear of getting infected, state health care professionals are underpaid and overworked.”

Theme 13. Healthcare profession is vital for the community.

Students’ comments about the healthcare profession indicated their understanding of the vital role the profession plays in the community. Respondent no. 8, a first professional year female student noted in this context, “Health professionals play a central and critical role in improving access and quality health care for the population.” Respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student observed how crucial was the role of healthcare professionals in dealing with the ‘pandemic’, a global health and life threat, “The Medical professionals have played a pivotal role in dealing with the pandemic…” Similarly, respondent no. 17, another first professional year male student remarked, “All the healthcare workers have acted as the first line of defence in this pandemic…”

Theme 14: Government and its policies play a pivotal role in healthcare.

Students understand the role of government in ensuring healthcare in the community. Respondents no. 4, 16, and 22, first professional year female students, indicated roles of government in healthcare related aspect in their remarks,

“…A major reason of all of the above shortcomings is a crippled healthcare system owing to the disinterest and disregard by the concerning governing authorities. Unavailability of a publicly funded health insurance in second largest population of the world is a cause of great concern, ”, “… many preventive measures were taken on large scale by government…”, and “… The medical fraternity should have training for epidemics and pandemic, the gov should have a special budget for the same,”, respectively.

Theme 15. It is a matter of pride!

Students take pride in being a part of the healthcare system. They hold medical professionals in high esteem. Respondent no. 8, a first professional year female student identified doctors as ‘heroes’ in her observation, “…Among the heroes who have emerged from this crisis are the health care professionals who have risked their own health to serve their patients. The nation is indebted to them.” She also mentions the nation being in debt towards healthcare professionals for their role in dealing with the pandemic. Respondent no. 8, another first professional year female student remarked doctors as ‘warriors’, “The Medical professionals have played a pivotal role in dealing with the pandemic. The front-line warriors without caring for their own lives have served the community and have set an example for the generations to come…”

Discussion

Medical professionalism and professional identity formation

A good practice of medicine requires a very high level of ethical and moral conduct on the part of its professionals. Different socio-cultural contexts may identify different attributes of the practice relevant to the same. Therefore, there is no one standard definition of medical professionalism. [9] However, the moral principles that describe a good human being are a reasonable minimum requirement for a good medical professional [10-12].

Also, in any medical education institute, students from different backgrounds come together for pursuing their professional training. Their personal standards of ethics and morals may be variable. And the environment of medical practice may be in stark contrast to the backgrounds they had been accustomed to. But they are all required to adopt good professional attributes, apart from learning curricular skills [13]. Here, the former remains less clearly defined, remains less clearly taught, and even less clearly learned [14]. Medical professionalism has therefore remained a difficult topic to teach and learn. Students learn it in classes as well as by observing and reflecting on what goes on around them. They try to relate themselves to different situations and form their own code of conduct. The latter remains dynamic – it keeps on evolving over the time the students spend in the practice of medicine, as a student and later as a practitioner. They form their own professional identities both with respect to their own individual personalities and with respect to their learning [6, 15]. The foremost step in the process is that the students clearly identify the attributes of good medical professional practice [8].

Reflection on the COVID–19 pandemic situation by medical students

The global response of healthcare professionals to the COVID-19 pandemic presents an exceptional learning opportunity for medical students to grasp the essence of their future profession [4, 5]. As Phase I and Phase II MBBS students were introduced to medicine and hospital settings, they encountered a unique learning obstacle when asked to observe the pandemic's impact from a distance [16]. This limited their academic and experiential understanding of medical practice and professional expectations. To bridge this gap, students were tasked with reflecting on healthcare professionals' roles during the pandemic, fostering a professional perspective on the situation [4, 5]. Despite being off-site, students attentively observed professionals' responses across healthcare delivery and research fields, identifying key attributes of medical practice to integrate upon their return to active learning environments [17]. Focused reflection acts as a cornerstone for more intentional learning of medical professionalism, contributing significantly to students' professional identity formation [12, 17, 18]. Analysis of students' reflection notes revealed a comprehensive spectrum of attributes associated with the medical profession, surpassing expectations. Students highlighted the significance of moral values, the profession's community impact, and governmental regulation, demonstrating a profound commitment to their professional growth. Notably, they recognized occupational hazards while expressing pride and accountability in their chosen path [19]. This sense of pride and responsibility contributes to their self-esteem and motivates them to excel as high-achieving professionals. Encouraging students to reflect on healthcare professionals' pandemic responses, therefore, empowered them to internalize essential aspects of medical practice and values. These reflections serve as foundational elements in shaping a future generation of conscientious and proficient healthcare providers, driven by a deep understanding of their profession's demands and rewards.

What other similar studies have found:

A literature search revealed several studies that have explored medical students' professional identity during COVID-19, although with different objectives and methodologies. These qualitative studies used reflective writing, group discussions, or interviews for data collection. Findyartini et al. (2020) [20] studied 80 reflection notes of medical students from different phases of the course at their institute. In the subthemes that they derived, they clearly mentioned students felt ‘empathy’ for their surroundings with respect to the pandemic situation. The students identified themselves with the role of ‘health educator’ and ‘role model’ for the ‘community’. Wurth et al. (2021) [21] studied 467 medical students’ responses to open-ended and close-ended questions in their online survey through a questionnaire. In their section on the Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ professional identity, they reported students acknowledging that they (the students) felt that the doctor-patient relationship there is deeper; the feeling of belonging to the health care workers and the vision of their commitment; and that the situation allowed them to realize the importance of health care professionals in our society; teamwork and communication are key to good collaboration and patient care; the importance of solidarity among health care professionals; a lot of kindness and goodwill are required; the importance of reassuring a patient, of creating trust, of being entirely conscious of potential stereotypes, and how to fight them; felt reassured to have chosen those studies; that a doctor can do a broad range of things, among the many other observations the authors made in their study. Byram, et al (2022) [22] discussed the reflections of 26 students regarding the role and image of a physician that students developed in view of the pandemic, among other themes. Students identified the profession as one ‘involving danger’. However, they ‘wanted themselves to be physicians’. And, they recognised the importance of ‘effective communication’ as physicians. Williams-Yuen et al. (2022) [23] interviewed 15 students of medical years 1-4 at their university regarding professional identity formation in COVID -19 setting. One of the themes, they identified in their data was ‘Physicians as Heroes”. Students observed the sacrifices doctors had to make to be that expected altruist, the responsibility they always bear, and their dangers. Moula et al. (2022) [24] analyzed 648 creative works along with reflective writing about them from students across the globe. Doctors have ‘social accountability’, they ought to be ‘unbiased’, and students taking ‘pride’ in the profession were among the themes of their findings that resonated with ours. Prade et al. (2023) [25] analysed 21 semi-structured interviews of medical students studying in the 8th and 9th semester at the University of Ulm. ‘Professional Competence’, ‘altruism’, ‘empathy’, ‘good communication’, and ‘sense of responsibility’ were among the aspects of medical professionalism that the students identified as important. Henderson et al. (2023) [26] examined professional identity formation as catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic among medical students at two medical schools in America through interviews, twice as they transitioned from the first medical professional year to second one. They found that students wanted to be public health ‘role models’, and that the pandemic prompted a ‘feeling of pride’ in them for being affiliated to the healthcare profession. They found that students also questioned the ‘self-sacrifice’ involved in the profession. And that physicians should take up leadership roles by ‘engaging in public health and political communication’. Though not exactly a match to our study’s perspective of broadly exploring the medical students’ take on the role of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, the themes and codes these authors have deduced in their works are quite similar to what we have found in our work.

We received responses from a fraction of the preclinical students with only 28 of them submitting reflective writing. Reasons for low participation may be varied, including discomfort with writing, lack of motivation, internet access issues, disinterest, or perceptions of virtual learning's relevance. Inferences drawn from our online study may not apply to non-participants. However, in the light of what other studies have found as cited in the discussion above, the findings of our study may not be completely non-generalizable. Another limitation may be the virtual mode of data collection: face-to-face discussions and writing typically yield more reliable data.

What we may thereby infer

We may reasonably deduce that the students continued their passive learning of medical professionalism and identity formation even when they were off the field by analysing the role of healthcare professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, this activity of reflection writing itself may have helped them to appreciate what their medical profession is about. The activity may also have facilitated in the process of their professional identity formation while they were away from the actual professional environment and teaching of the same. We may expect them to have learned these aspects more coherently when they returned to their institute when the lockdowns were discontinued.

Conclusion

The preclinical students were able to grasp the scope of their profession even while being distant from actual hospital and academic settings during the pandemic by critically observing and analyzing the response of healthcare professionals to COVID-19. Activities such as focused group discussions and reflective writing appear to have been beneficial in this process.

Although these findings are not generalizable, they support the provision of remote learning opportunities and observational learning. Medical institutes could benefit from incorporating more case studies, reflective writing assignments, and focus group discussions to enhance understanding of real-world situations, even when direct clinical exposure is limited. Furthermore, these institutions could increase engagement with local healthcare facilities to offer observational internships to students. Future research that explores cross-cultural variations in the understanding of medical professionalism and the formation of professional identity through remote learning, in comparison to to hands-on dynamic training, along with longitudinal follow-up, could be very useful in further elucidating how medical students internalize these core professional values.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of DMIMS (DU): DMIMS (DU)/IEC/2020-21/9060 dated 10.10.2020

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT3.5 and 4) was used in revising the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all the students who participated in the study and submitted their reflective writing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Prerna Agarwal- concept, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafting and reviewing of manuscript, approval of final version. Dalia A. Biswas: design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafting and reviewing of manuscript, approval of final version.

FundingStudents quoted various instances as to how the doctors disregarded their own interests to work for the larger benefit of the people, and how they risked their own lives for treating patients. Respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student observed that,

“...When the staff came for collecting samples, people had different, some were cooperative and some were not. But then too, not keeping this in mind, these people did take all the samples, some gave swab samples and some took rapid antigen test. This shows that the medical professionals involved gave their best efforts they didn't discriminate between people … even after violence, non-cooperation from people, they didn't back down.”

Another student, a second professional year male student (Respondent no. 14) expressed, “… medical profession is the only profession where the professionals are still doing their job without much changes in there working pattern, OPD still are full with verities of patient where some understand the importance of current scenario but many don't and as a doctor you ignore those things and indulge yourself in treatment of others.”

Some students clearly stated that the medical profession is all about ‘helping others’ (Respondent no. 12, a male student of first professional year).

And in turn, some students acknowledged that the same inspired them ‘to do their best in helping people in need’ (Respondent no. 7, a first professional year female student).

Theme 2. Medical Professionals should have ‘good communication and other soft skills.’

Students mentioned that doctors need to have good communication and other soft skills while dealing with patients and their relatives/ caretakers. They stated how the same helps in establishing trust and understanding between them, and avoid conflict. A first professional year female student (Respondent no. 3) observed that

“….Proper counselling of family members of COVID-19 patient is being done by the doctors which is very important….”

Another first professional year female student (Respondent no. 28) thought that, “…effective communication amongst doctor and patient also the patient’s family need to be properly informed about the condition of the patient….”

Another first professional year female student noted (Respondent no. 04) that “….Majority of doctors find themselves struggling to choose right words when it comes to communicating with the kins of the patients. A lot of violence could be avoided by rightful exchange of words.”

A first professional year male student expressed (Respondent no. 27) that “…I learned that we need to first go to the patient then talk in a good manner, then take the permission asking him/her to diagnose or test etc.”

They mentioned that they will be “Working towards improving personal communication skills; Understanding the importance of establishing a good doctor patient relationship; Being an effective and responsible spokesperson for the medical community…” (Respondent no.5, a first professional year female student) , and that “.I would try to establish an understanding between me and person (patient)” (Respondent no. 24, a first professional year male student).

Theme 3. Doctors need to be ‘competent in their skills and should strive for continuous improvement’.

Students pointed out the need for being sound in knowledge and application, need for research in the field and having a scientific temperament. They vowed to inculcate the necessary skills in themselves. One first professional-year female student (Respondent no. 4) expressed that,

“Below are the following things that the current situation has made me realise: Development of a scientific temperament at an undergraduate level and constantly trying to adapt the same in day-to-day life…...”

“The importance of research has been brought up by this pandemic” was observed by respondent no. 9, a first professional year female student.

Another first profession year female student, (Respondent no. 16) stated that “Doctors have not only work on the treatment part but also the research part to get the right vaccine and to cure this virus from roots.”

A first professional year male student (Respondent no. 12) said that “In my future practice I will try to make the best use of my knowledge.”

Theme 4. Doctors ought to be ‘empathetic’ towards their patients.

Students put forth the importance of empathy for the patients and their care takers, and their own commitment for developing the same in their own behaviour.

“…Proper counselling of family members of COVID-19 patient is been done by the doctors which is very important. Not only by medical treatment but emotional support and empathy is also given by doctors,” was expressed by the first professional year female student (Respondent no.3).

“….since in the covid ward only the patient is allowed to stay the family member are always in stress and panic to know about the situation of the patient and is always curious to know about the recovery status of patient. So here comes the role of a doctor to inform about the situation of the patient and the treatment been given to them. This helps to keep hope and faith on the doctors. As they feel that their family member is in good hands,” was observed by the respondent no. 28, a first professional year female student.

“…and make a good relationship of empathy and respect for my patients,” was stated by respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student.

Likewise, respondent no. 24, a first professional year male student stated that, “...I would try to establish an understanding between me and person…”

Theme 5. Doctors should uphold ‘integrity of their character’ at all times.

Some students could identify that doctors should be virtuous in their character. They should be honest, dedicated and should not discriminate.

Respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student stated that, “…I believe that whoever is a part of the healthcare system should be dedicated and honest to their work only then can we defeat such disasters….”

Respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student observed that “…didn't discriminate between people…”

“People believe what doctors say. It is this trust which we have to keep strong as we, the medical professionals are the only sources of hope for the people and that’s the most important thing we should have in our minds…”, was expressed by respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student.

Theme 6. A sense of responsibility and accountability prevails in the medical profession.

Students understood the responsibility doctors bear on their shoulders. They could recognise their being accountable for the well-being of their patients and healthcare needs of the society in general. They said they would conduct themselves in an appropriate manner.

“…doctors have a great responsibility on their shoulders in such times...” noted respondent no. 10, a first professional year female student.

“…because it's their duty…” said respondent no. 7, another first professional year female student.

“…this profession is not for experimentation but a planned right action and decision has to be taken at right time. One mistake and we could lose the patient's life. This pandemic is a lesson…” said respondent no. 16, a first professional year female student. She also expressed that, “I am very inspired by the medical professionals during pandemic. It has raised a greater sense of responsibility within me towards the society.”

Another first professional year female student, respondent no. 4, stated that she would practice medicine “...keeping in mind how my actions could potentially harbour a feeling of distrust among general population.”

Theme 7. Medical profession is a ‘team work’.

Students cited many instances where they identified doctors/ healthcare professionals working as a team, and cooperating with each other. One first professional year female student, respondent no. 10, noted that, “….doctors who are although not working in the covid hospitals, but still, they are spreading awareness and asking people to wear masks and maintain hand hygiene. Not only this, the groups that have been formed by the administration that has a doctor with them…”

Another first professional year male student, respondent no 12, noted that, “…. It’s not only about the doctor but the credit goes to the entire team of 12 people who assisted the doctor and played different roles in the lab.”

Similarly, respondent no 5, another first professional year female student, observed that, “…they are really working very hard for us ........they work together as a group.”

Theme 8. Doctors should be able to ‘lead and guide’.

Some students mentioned that doctors should be able to assume leadership roles:

In this context, respondent no. 4, a first professional year female student expressed, “….I have realized the importance of supporting leadership qualities as a part of medical education…”

Students identified serving the community as the duty of healthcare professionals, including themselves as students. Respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student observed, “…the medical professionals and other people associated in any way with treating and serving the people….” Similarly, respondent no. 7, another first professional year female student also identified the word ’duty’, saying, “…are doing this because it's their duty.”Another respondent, no. 8, a first professional year female student, also used the words ‘serve’ and ‘duty’ while expressing, “…. Medical students are adept at many clinical roles. Allowing them to serve…. Should be allowed to fulfill their duties as such.”

Theme 10. Medical Profession involves a lot of ‘hard work’.

Students clearly pointed out the hard work that doctors put in:

“…physicians and health care professionals for their hard work, thoughtfulness, and commitment during this challenging time,” said respondent no.8, a first professional year female student. Respondent no. 5, a first professional year female student, also used the phrase ‘hard work’, “….they are really working very hard for us…”

Respondent no. 21, a first professional year male student observed, “…I have seen doctors, nurses working in double digit hours in PPE for the well-being of diseased people.” Similarly, respondent no. 27, also a first professional year male student noted,

“...I observed that doctors are working round the clock, they are not having proper food at time, Doctors are moving with covid patients all the time. They also have a family but they are ready to serve the patients in this pandemic situation. As, this disease being a highly contagious one doctors need to put on PPE kit all the time, I cannot express how they suffocate...”

Yet another respondent, no. 28, a first professional year female student observed, “…medical professionals have been overworked.”

Theme 11. Medical Profession calls for self-sacrifice.

Students also recognized the self-sacrifice involved in the practice of health care.

“Medical professionals were suddenly thrust upon huge responsibility of saving everyone catering to their needs but with zero precautions and minimal paygrade and protection,” and, “… all the professionals without caring about themselves working for world health shows our contribution and sacrifices,” said respondent no. 2, a first professional year female student to emphasise that doctors compromise their own needs. She also felt that, “The medical professionals are doing their best to help people, protecting them, staying away from their family to keep them safe as well.”

Respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student said doctors risked their won lives for patients’ sake, “...The COVID- 19 Pandemic situation is very difficult for everyone especially the medical professionals and other people associated in any way with treating and serving the people as they are risking their own lives, staying away from their own families for days and months and are stepping forward to help the society without thinking anything of their own good.”

Similarly, respondent no. 26, a first professional year male student also felt “Doctors trying hard to save lives by keeping their (own) life at stake.”

Theme 12. Medical Profession has its own set of perils.

Students identified many situations involving hazards, challenges to the healthcare professionals themselves, and how doctors put their duty ahead of their own interests. They also highlighted the lacunae in safety, and protection of healthcare professionals, and even lack of adequate acknowledgement of their contribution. Respondent no 3, a first professional year female student observed doctors contracting the disease from patients, “…In some cases, doctors are also being infected with COVID-19 during treatment of patients….”

In her expression,“…how the doctors are disrespected, even have to face some physical harms by the people in the society whom they serve….” respondent no. 11, a first professional year female student, highlighted assaults, out of fear, or misinformation, on doctors.

Respondent no. 15, another first professional year female, highlighted over work, need for rest, and abuse of doctors in the context, “….The doctors need rest. Patients need to take that into consideration. After working 24×7 this is not what they expect. I have seen patients getting extremely abusive towards the doctor for not treating their patient even though the doctor was himself not well…”

Similarly, respondent no. 17, a first professional year male student, also identified aggressions against doctors, “…, they acted as first line of defence during this pandemic, and even after violence, non-cooperation from people, they didn't back down, and I don't think anyone else could have done it in this way….”

Likewise, respondent no. 24, also a first professional year male student stated “…People were afraid of virus and they saw medical professionals as a connection to virus. During pandemic I went to photograph shop. He was not welcoming for me in apron and asked me to leave so there was some fear against medical professionals which can be harmful sometimes.”

Respondent no. 4, a first professional year female student identified ‘impairment of human rights of doctors’ in her expression,“….Further the improper implementation of laws has impaired the human rights of doctors leading to multiple protests.” Respondent no. 28, a first professional year female student identified ‘stigma’ being associated with medical personnel and their families, “...medical professionals have been overworked, general population usually tries to avoid them, medical professional families not treated well and stigmatized from the potential fear of getting infected, state health care professionals are underpaid and overworked.”

Theme 13. Healthcare profession is vital for the community.

Students’ comments about the healthcare profession indicated their understanding of the vital role the profession plays in the community. Respondent no. 8, a first professional year female student noted in this context, “Health professionals play a central and critical role in improving access and quality health care for the population.” Respondent no. 12, a first professional year male student observed how crucial was the role of healthcare professionals in dealing with the ‘pandemic’, a global health and life threat, “The Medical professionals have played a pivotal role in dealing with the pandemic…” Similarly, respondent no. 17, another first professional year male student remarked, “All the healthcare workers have acted as the first line of defence in this pandemic…”

Theme 14: Government and its policies play a pivotal role in healthcare.

Students understand the role of government in ensuring healthcare in the community. Respondents no. 4, 16, and 22, first professional year female students, indicated roles of government in healthcare related aspect in their remarks,

“…A major reason of all of the above shortcomings is a crippled healthcare system owing to the disinterest and disregard by the concerning governing authorities. Unavailability of a publicly funded health insurance in second largest population of the world is a cause of great concern, ”, “… many preventive measures were taken on large scale by government…”, and “… The medical fraternity should have training for epidemics and pandemic, the gov should have a special budget for the same,”, respectively.

Theme 15. It is a matter of pride!

Students take pride in being a part of the healthcare system. They hold medical professionals in high esteem. Respondent no. 8, a first professional year female student identified doctors as ‘heroes’ in her observation, “…Among the heroes who have emerged from this crisis are the health care professionals who have risked their own health to serve their patients. The nation is indebted to them.” She also mentions the nation being in debt towards healthcare professionals for their role in dealing with the pandemic. Respondent no. 8, another first professional year female student remarked doctors as ‘warriors’, “The Medical professionals have played a pivotal role in dealing with the pandemic. The front-line warriors without caring for their own lives have served the community and have set an example for the generations to come…”

Discussion

Medical professionalism and professional identity formation

A good practice of medicine requires a very high level of ethical and moral conduct on the part of its professionals. Different socio-cultural contexts may identify different attributes of the practice relevant to the same. Therefore, there is no one standard definition of medical professionalism. [9] However, the moral principles that describe a good human being are a reasonable minimum requirement for a good medical professional [10-12].

Also, in any medical education institute, students from different backgrounds come together for pursuing their professional training. Their personal standards of ethics and morals may be variable. And the environment of medical practice may be in stark contrast to the backgrounds they had been accustomed to. But they are all required to adopt good professional attributes, apart from learning curricular skills [13]. Here, the former remains less clearly defined, remains less clearly taught, and even less clearly learned [14]. Medical professionalism has therefore remained a difficult topic to teach and learn. Students learn it in classes as well as by observing and reflecting on what goes on around them. They try to relate themselves to different situations and form their own code of conduct. The latter remains dynamic – it keeps on evolving over the time the students spend in the practice of medicine, as a student and later as a practitioner. They form their own professional identities both with respect to their own individual personalities and with respect to their learning [6, 15]. The foremost step in the process is that the students clearly identify the attributes of good medical professional practice [8].

Reflection on the COVID–19 pandemic situation by medical students

The global response of healthcare professionals to the COVID-19 pandemic presents an exceptional learning opportunity for medical students to grasp the essence of their future profession [4, 5]. As Phase I and Phase II MBBS students were introduced to medicine and hospital settings, they encountered a unique learning obstacle when asked to observe the pandemic's impact from a distance [16]. This limited their academic and experiential understanding of medical practice and professional expectations. To bridge this gap, students were tasked with reflecting on healthcare professionals' roles during the pandemic, fostering a professional perspective on the situation [4, 5]. Despite being off-site, students attentively observed professionals' responses across healthcare delivery and research fields, identifying key attributes of medical practice to integrate upon their return to active learning environments [17]. Focused reflection acts as a cornerstone for more intentional learning of medical professionalism, contributing significantly to students' professional identity formation [12, 17, 18]. Analysis of students' reflection notes revealed a comprehensive spectrum of attributes associated with the medical profession, surpassing expectations. Students highlighted the significance of moral values, the profession's community impact, and governmental regulation, demonstrating a profound commitment to their professional growth. Notably, they recognized occupational hazards while expressing pride and accountability in their chosen path [19]. This sense of pride and responsibility contributes to their self-esteem and motivates them to excel as high-achieving professionals. Encouraging students to reflect on healthcare professionals' pandemic responses, therefore, empowered them to internalize essential aspects of medical practice and values. These reflections serve as foundational elements in shaping a future generation of conscientious and proficient healthcare providers, driven by a deep understanding of their profession's demands and rewards.

What other similar studies have found:

A literature search revealed several studies that have explored medical students' professional identity during COVID-19, although with different objectives and methodologies. These qualitative studies used reflective writing, group discussions, or interviews for data collection. Findyartini et al. (2020) [20] studied 80 reflection notes of medical students from different phases of the course at their institute. In the subthemes that they derived, they clearly mentioned students felt ‘empathy’ for their surroundings with respect to the pandemic situation. The students identified themselves with the role of ‘health educator’ and ‘role model’ for the ‘community’. Wurth et al. (2021) [21] studied 467 medical students’ responses to open-ended and close-ended questions in their online survey through a questionnaire. In their section on the Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ professional identity, they reported students acknowledging that they (the students) felt that the doctor-patient relationship there is deeper; the feeling of belonging to the health care workers and the vision of their commitment; and that the situation allowed them to realize the importance of health care professionals in our society; teamwork and communication are key to good collaboration and patient care; the importance of solidarity among health care professionals; a lot of kindness and goodwill are required; the importance of reassuring a patient, of creating trust, of being entirely conscious of potential stereotypes, and how to fight them; felt reassured to have chosen those studies; that a doctor can do a broad range of things, among the many other observations the authors made in their study. Byram, et al (2022) [22] discussed the reflections of 26 students regarding the role and image of a physician that students developed in view of the pandemic, among other themes. Students identified the profession as one ‘involving danger’. However, they ‘wanted themselves to be physicians’. And, they recognised the importance of ‘effective communication’ as physicians. Williams-Yuen et al. (2022) [23] interviewed 15 students of medical years 1-4 at their university regarding professional identity formation in COVID -19 setting. One of the themes, they identified in their data was ‘Physicians as Heroes”. Students observed the sacrifices doctors had to make to be that expected altruist, the responsibility they always bear, and their dangers. Moula et al. (2022) [24] analyzed 648 creative works along with reflective writing about them from students across the globe. Doctors have ‘social accountability’, they ought to be ‘unbiased’, and students taking ‘pride’ in the profession were among the themes of their findings that resonated with ours. Prade et al. (2023) [25] analysed 21 semi-structured interviews of medical students studying in the 8th and 9th semester at the University of Ulm. ‘Professional Competence’, ‘altruism’, ‘empathy’, ‘good communication’, and ‘sense of responsibility’ were among the aspects of medical professionalism that the students identified as important. Henderson et al. (2023) [26] examined professional identity formation as catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic among medical students at two medical schools in America through interviews, twice as they transitioned from the first medical professional year to second one. They found that students wanted to be public health ‘role models’, and that the pandemic prompted a ‘feeling of pride’ in them for being affiliated to the healthcare profession. They found that students also questioned the ‘self-sacrifice’ involved in the profession. And that physicians should take up leadership roles by ‘engaging in public health and political communication’. Though not exactly a match to our study’s perspective of broadly exploring the medical students’ take on the role of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, the themes and codes these authors have deduced in their works are quite similar to what we have found in our work.

We received responses from a fraction of the preclinical students with only 28 of them submitting reflective writing. Reasons for low participation may be varied, including discomfort with writing, lack of motivation, internet access issues, disinterest, or perceptions of virtual learning's relevance. Inferences drawn from our online study may not apply to non-participants. However, in the light of what other studies have found as cited in the discussion above, the findings of our study may not be completely non-generalizable. Another limitation may be the virtual mode of data collection: face-to-face discussions and writing typically yield more reliable data.

What we may thereby infer

We may reasonably deduce that the students continued their passive learning of medical professionalism and identity formation even when they were off the field by analysing the role of healthcare professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, this activity of reflection writing itself may have helped them to appreciate what their medical profession is about. The activity may also have facilitated in the process of their professional identity formation while they were away from the actual professional environment and teaching of the same. We may expect them to have learned these aspects more coherently when they returned to their institute when the lockdowns were discontinued.

Conclusion

The preclinical students were able to grasp the scope of their profession even while being distant from actual hospital and academic settings during the pandemic by critically observing and analyzing the response of healthcare professionals to COVID-19. Activities such as focused group discussions and reflective writing appear to have been beneficial in this process.

Although these findings are not generalizable, they support the provision of remote learning opportunities and observational learning. Medical institutes could benefit from incorporating more case studies, reflective writing assignments, and focus group discussions to enhance understanding of real-world situations, even when direct clinical exposure is limited. Furthermore, these institutions could increase engagement with local healthcare facilities to offer observational internships to students. Future research that explores cross-cultural variations in the understanding of medical professionalism and the formation of professional identity through remote learning, in comparison to to hands-on dynamic training, along with longitudinal follow-up, could be very useful in further elucidating how medical students internalize these core professional values.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of DMIMS (DU): DMIMS (DU)/IEC/2020-21/9060 dated 10.10.2020

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT3.5 and 4) was used in revising the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all the students who participated in the study and submitted their reflective writing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Prerna Agarwal- concept, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafting and reviewing of manuscript, approval of final version. Dalia A. Biswas: design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafting and reviewing of manuscript, approval of final version.

None

Data availability statement

Upon a reasonable request, the corresponding author can provide the datasets analyzed in this study.

Supplementary

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1id-Mb30y88-3OXjYANDESAyzVRfda2pI/view?usp=sharing

Article Type : Orginal Research |

Subject:

Medical Education

Received: 2024/04/23 | Accepted: 2024/08/1 | Published: 2025/04/14

Received: 2024/04/23 | Accepted: 2024/08/1 | Published: 2025/04/14

References

1. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. WHO;2024. [Online]. Available from: [Accessed: Jul. 6, 2024]. [DOI]

2. Larkin H. Navigating attacks against health care workers in the covid-19 era. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2021;325(18):1822–24. [DOI]

3. Mehta S, Machado FR, Kwizera A, et al. Covid-19: a heavy toll on health-care workers. The Lancet. 2021;9(3):226–8 [DOI]

4. Agarwal P, Gupta VK. Covid 19 pandemic: an opportunity to investigate medical professionalism. Canadian Medical Education Journal. 2020;12(1): e103-e104. [DOI]

5. Shi W, Jiao Y. The covid-19 pandemic: a live class on medical professionalism. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2020;114(9):677–8. [DOI]

6. Cullum RJ, Shaughnessy A, Mayat NY, Brown ME. Identity in lockdown: supporting primary care professional identity development in the covid-19 generation. Education for Primary Care. 2020;31(4):200–204. [DOI]