BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://edujournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-1588-en.html

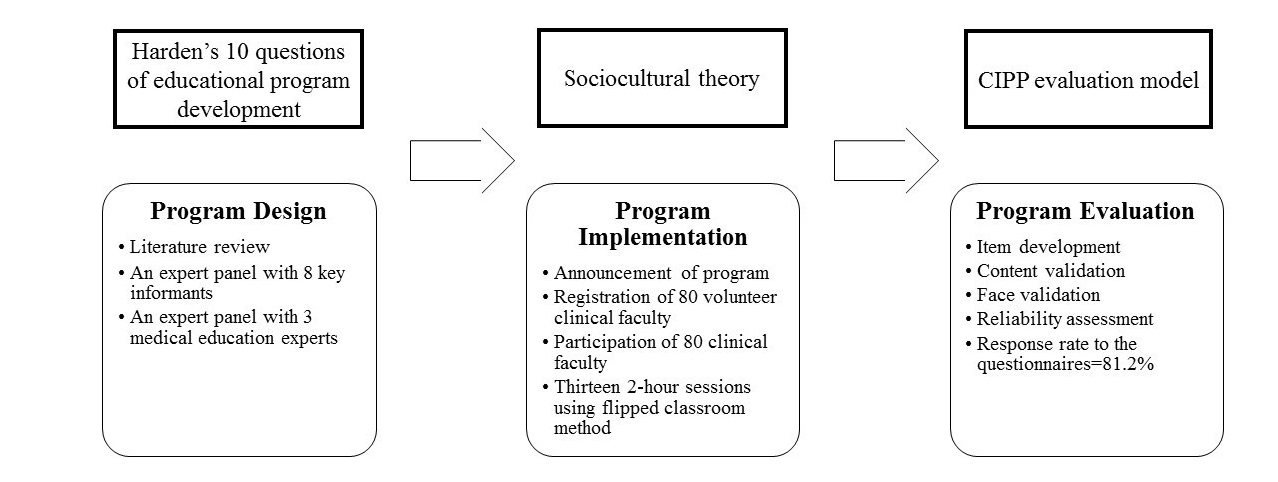

Materials & Methods: This triangulation study was conducted from September 2021 to February 2022. The program designed by adopting Harden’s 10 Questions of educational program development framework approach. Based on Sociocultural theory, a longitudinal, informal program performed in a group setting for eighty clinical faculty members. For program evaluation, a questionnaire based on the CIPP evaluation model was developed and tested psychometrically.

Results: The results indicated the overall satisfaction with faculty development program was high. Participants reported awareness of strengths and weaknesses in education, more self-confidence, higher motivation in teaching, acquiring teaching skills in clinical settings, and providing effective feedback as the program's achievements.

Conclusion: The combination of informal, longitudinal, and group-based approach increased the program's efficiency. This approach had short-term results such as enhancement of participants’ educational skills, improvement in the process of clinical education, and training clinical educators for future faculty development programs. hopefully, it will increase organizational capacities in the long time.

Introduction

Evidence shows that personal motivation, experience, and clinical expertise are insufficient for a standard clinical education process (5). Educational faculty development programs for clinical faculty are suitable opportunities to improve their educational skills and enhance the clinical education process (6).

Despite the notable time and efforts spent in medical universities to offer educational faculty development programs for clinical faculty, the results indicate low efficiency due to some challenges and limitations. Some of these obstacles are the faculty members’ heavy workload and their limited time (7, 8). Some weaknesses are in designing and implementing the faculty development programs. These challenges are include not embedding the program in a theoretical or conceptual framework (4), not utilizing theory in the interpretation of the results, performing short courses (9), and lack of follow-up on the participants’ educational activities after the program (10).

Due to the importance of educational faculty development programs for clinical faculty members, there is a need to revise the current programs. This study aimed to design, implement and evaluate a long-term educational faculty development program for clinical faculty members.

Material & Methods

Study design and setting

This triangulation study was conducted at Kerman University of Medical Sciences from September 2021 to February 2022.

Program design

The faculty development program designed by adopting Harden’s 10 Questions of educational program development framework (11). According to this framework, the educational needs, aim and objectives, content and its organization, educational strategies and teaching methods, program evaluation method, announcement about the details of the program, educational environment, and program management were addressed.

To determining the educational needs of clinical faculty members, we reviewed the relevant literature and conducted an expert panel using the nominal group technique with eight key informants including six clinical faculty members and two medical education experts.

The expert group was invited via email and, then invitations were confirmed in person and the purpose of the panel was explained. In the first step of the nominal group technique, participants were asked the main question: "What are the educational needs of clinical faculty members?”. Next, each participant independently and privately wrote down their individual ideas. Then the written needs were shared with the group in a round-robin format. In the next step, with the assistance of a facilitator, participants discussed the list of educational needs and their priority was put to the vote.

The results from the expert panel and findings of the literature review were presented in a panel consisting of three medical education experts, and the aim and objectives of the program were specified.

Program Implementation

A longitudinal, informal program performed in a group setting were chosen based on Sociocultural theory (12). After the announcement of the faculty development program, eighty clinical faculty members registered voluntarily and all of them participated in the program. Thirteen 2-hour sessions were held using flipped classroom method. In this regard, for each session, firstly, the electronic educational content was uploaded to Learning Management System according to a specific timetable. Then, a synchronize online session aimed at discussion and practice was held. In this session, participants reflected on their experiences using a semi-structured method and discussed the topic.

Program Evaluation

A researcher-made questionnaire based on the context, input, process, and product model (CIPP) (13) was used for program evaluation. The items in the questionnaire were developed based on reviewing the studies about the evaluation of faculty development programs. The context domain evaluated the educational needs of clinical faculty members, the aim and objectives of the program, and the adapting goals to the needs. The input domain evaluated content and its organization, educational strategies, and teaching methods. The process domain evaluated the problems in the program's implementation. The product domain evaluated the program results. The questionnaire also included some close and open-ended questions to investigate the participants' satisfaction and opinion about the program.

Content validity was investigated by computing content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). For investigating face validity, five experts were asked to provide comments about the simplicity of each question and their fluency. Reliability assessment was studied by Cronbach's alpha. Internal consistency of more than 0.7 was considered suitable.

The overall CVR was 0.71, which was acceptable. The CVI for all items was 0.83 (In terms of relevance 0.81, clarity 0.80, and simplicity 0.87). Some items were corrected after face validity. Cronbach alpha coefficient for all items of the questionnaire was 0.80.

After investigating reliability and validity, the final questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part included demographic information (gender, academic rank, and educational department). The second part contained 20 multiple-choice questions, including five questions for context evaluation, five questions for input evaluation, five questions for process evaluation, and five questions for product evaluation. These questions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, scored from 5 to 1 for statistical comparison. The questionnaire also included five close and open-ended questions to investigate the participants' satisfaction and opinion about the program.

The final electronic version of the questionnaire was sent to the participants of the faculty development program. It was redistributed one more time at an approximately 2-week interval, via E-mail and also followed up through social media. The data were analyzed using SPSS.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Center for Strategic Research in Medical Education (No. IR.NASRME.REC.1400.472). Participants did not receive any incentives, and participation was voluntary. Verbal and written consent for participation was obtained based on the proposal approved by the ethics committee. The participants were also assured of the confidentiality of their information, and it was explained that the results would only be used for research objectives. The overall design, implementation and evaluation process of the educational faculty development program for clinical faculty is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overall design, implementation and evaluation process of the educational faculty development program for clinical faculty

Results

In the design phase of the faculty development program, eight key informants participated in the nominal group to determine the educational needs of clinical faculty members. The majority of them (76.7%) were women. Almost half (62.5%) were assistant professors, 25% were associate professors, 12.5% was professor. Three general categories including "clinical education", "clinical assessment" and "clinical professionalism" were considered educational needs (Table 1).

Table 1. The educational needs of clinical faculty members for faculty development program

|

General category |

Educational needs |

|

Clinical Education |

Morning reports |

|

Ambulatory teaching |

|

|

Clinical rounds |

|

|

Feedback in the clinical setting |

|

|

Simulators in medical education |

|

|

Virtual education in clinical practice |

|

|

Clinical Assessment |

Work place-based assessment: DOPS, Mini-CEX, Logbook, Portfolio, |

|

Clinical reasoning assessment: Key Features, Clinical Reasoning |

|

|

Clinical Professionalism |

Clinical faculty members in the role of educators |

|

Role modeling |

|

|

Breaking bad news |

The aim of the program was capacity development in clinical education. The objectives were to improve the individual educational competencies of clinical faculty members and to train educators from the clinical faculty members to teach in future faculty development programs. The contents organized from basic to advance.

In the implementation phase, eighty clinical faculty members participated in the program after registration. The participants’ demographics of the faculty development program are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Participants’ demographics of the faculty development program

|

Variable |

Number (%) |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

24 (30) |

|

Female |

56 (70) |

|

|

Rank of faculty |

Assistant professor |

79 (98.7) |

|

Associate professor |

1 (1.2) |

|

|

Educational Department |

Internal Medicine |

43 (53.7) |

|

General Surgery |

12 (15) |

|

|

Pediatrics |

7 (8.7) |

|

|

Obstetrics and Gynecology |

6 (7.5) |

|

|

Orthopedics |

5 (6.2) |

|

|

Dermatology |

4 (5) |

|

|

Radiotherapy |

2 (2.5) |

|

|

Emergency Medicine |

1 (1.2) |

|

|

Participants |

80 |

|

In the evaluation phase, the response rate to the questionnaire was 81.2%. The majority of respondents (80%) were women. Almost all (98.4%) were assistant professors, and just one respondent was an associate professor. Most of the respondents were affiliated with the internal medicine department (61.5%), and 15.3% were from general surgery department. The Pediatrics respondents (9.2%) were almost equal in number to the respondents from obstetrics and gynecology department (7.6%). The respondents from orthopedics department were 4.6% and one respondent was from dermatology department (1.5%).

The mean (SD) of participants' satisfaction was 71.76 (4.29), indicating high overall satisfaction with the faculty development program. These results indicate that the informal and group-based approach is suitable for clinical faculty members who have a heavy work-load and limited time.

The mean (SD) of all items’ scores in terms of context evaluation, input evaluation, process evaluation, and product evaluation were 3.47 (0.35), 4.0 (17.34), 4.32 (0.47), and 4.41 (0.40), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean and standard deviation in the context, input, process, and product evaluation scores

|

P-Value* |

T |

Mean) SD) |

Domain |

|

0.30 |

1.02 |

3.47 (0.35) |

Context |

|

0/04 |

-2/07 |

4.17 (0.34) |

Input |

|

0.29 |

1.06 |

4.32 (0.47) |

Process |

|

0.81 |

-0.23 |

4.41 (0.40) |

Product |

|

significance level, is set to 0.05* |

|||

The lowest score was attributed to the context domain and the highest was about the product evaluation of the program. Independent t-test showed no significant difference between the mean scores of context, input, process, and product domain (P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study aimed to design, implement and evaluate a long-term educational faculty development program for clinical faculty members. Harden’s 10 Questions of educational program development framework approach was adopted to design this program. In the implementation phase, a longitudinal, informal program in a group setting was considered based on Socio-cultural theory. The program was evaluated using the CIPP evaluation model.

Using Harden’s 10 Questions of educational program development framework approach as a systematic approach provided high-quality evidence of program designing. This well-structured and conceptualized approach goes beyond the conventional emphasis on just goals and educational methods in designing an educational program. It may be that the organizational impact of faculty program design will be of more long-term efficacy rather than simple improvement of program material (14). Sezer and the colleague (2021) developed a faculty development program consisting of six modules, 34 hours, and various teaching strategies in nursing education based on Harden’s model. They reported this program's advantages, including increasing students' academic success, developing their clinical practices and generating a constant learning environment (15).

The relevance of content to the participants’ work and responsibility to address the professional needs of faculty was frequently highlighted in the review of Steinert et al. (2016) (4). Tenzin and colleagues (2019) designed a faculty development program based on educational need assessment. They reported significant improvements in teacher self-efficacy in the domain of teaching, developing creative ways to cope with system constraints and improvement of their communication skills (16). In our study, the incorporation of clinical faculty’s educational needs, including "clinical education", "clinical assessment" and "clinical professionalism" with the content of the program was a key feature. Some of these findings have been noted in previous studies that had focus on the need assessment of faculty development programs. Manzoor et al. (2018) identified areas for faculty development programs, including educational psychology, teaching skills, assessment techniques, educational research, and management skills for 194 clinical and basic science faculty (17).

The present study's results align with the findings of Abdelkreem et al. (2020), which assessed the perceived development needs of medical faculty and the factors affecting these needs. They determined that designing a faculty development program adjusted to faculty members' needs would promote professional growth (18).

Application of a longitudinal, informal, and group-based approach grounded on Sociocultural theory in the implementation phase argued that the developmental theories of Vygotsky resting on the concepts of the social basis of mental functions, agreement of performance and awareness, mediation, and mental structures can help more richly understand the faculty development in their workplaces. Shabani (2016) outlined that the sociocultural theory of professional development embraces both the theoretical and practical features. It creates relations between theory and practice by illustrating the multifaceted mechanisms of learning procedures in real sociocultural settings (19). Hora et al. (2021) emphasize the need to use sociocultural theory in faculty development programs to inform broader contexts of teachers' interaction in faculty development programs and to determining how individual capacities are generated (20).

Lippe et al. (2018) used the CIPP model to evaluate a nursing education program. The results showed that this model serves as a practical guide for in-depth and comprehensive evaluation of educational programs (21). Molope and colleagues (2020) evaluated a community development practitioners program using the CIPP model and reported that the benefits of this model lead to the evaluation of all influential factors from designing to implementation and evaluation of the faculty development program and provided valuable guidelines for improving future programs (22).

A wide range of long-term or short-term activities, formal or informal, individual or group-based approaches including workshops, seminars, mentorship programs, work-based learning, communities of practice, electronic and online learning, reflecting on experience, learning by observing peer coaching, and longitudinal programs such as fellowships can be considered for faculty development of clinical faculty members (4). Studies evaluating the faculty development programs have reported various levels of individual and organizational effects (23). The faculty development programs are implemented in the form of short-term and formal courses such as workshops and seminars. The results of these programs are the individual development of the faculty members (24). In some other cases, formal and individual approaches such as learning by observing peer coaching and mentorship are used. The results of such short-term or long-term programs are reflected in the personal and professional development of the faculty members (25). A limited number of policymakers of faculty development programs consider informal approaches such as work-based learning and communities of practice which impact at the organizational level (26). An informal and group-based approach provides an opportunity for reflecting on experiences and group discussion. These approaches greatly impact individual and organizational capacities to adapt and perform activities in a complex clinical setting with various underlying factors. However, these approaches have been used in a few cases (27).

Group discussion and interaction in education is rooted in sociocultural theory. According to this theory, learning is a socially mediated process in which individuals acquire knowledge through collaborative dialogues with more knowledgeable members of society (28). Therefore, reflection on experience and group discussion lead to the faculty members' active role in learning educational skills. Our positive results because of using the concepts of sociocultural theory are consistent with previous studies. Qureshi (2021) applied the sociocultural theory in medical education and revealed that this theory could be efficiently used on various levels of medical sciences education, including undergraduate education, postgraduate education, and continuous professional development (12).

In the present study, the combination of informal, longitudinal and group-based approaches greatly increased its effectiveness, leading to results such as enhancement in the process of clinical education and training clinical educators for future faculty development programs. These results are confirmed in the results of Salajegheh (2021), that studied the contribution of a long-term faculty development program to organizational development through capacity development (23).

In response to the open-ended questions of the questionnaire, the faculty reported awareness of strengths and weaknesses in education, increasing self-confidence and higher motivation for teaching, acquiring teaching skills in clinical settings, and providing effective feedback as the program's achievements. These outcomes are likely to be developed by the longitudinal approach of the program. As Steinert (2020) described, faculty development programs that extend over time yield results that go beyond teaching effectiveness and be more permanent (24).

One of the most notable findings was the agreement of faculty on the importance of collective participation for better learning. These outcomes are consistent with the impact of faculty development programs studied by prior research. Carvalho-Filho and colleagues (2020) described that communities of practice for faculty development suggest an effective and sustainable approach for implementing best practices (29).

Moreover, the results indicated that the participants believed the program's content addressed their professional needs specifically. Wong et al. (2020) similarly enhanced teaching proficiency at the end of their educational intervention for clinical faculty with a program that included relevant specific content (30).

Limitation and recommendation

One of the limitations of the present study was the implementation of the program in only one university, which may restrict the generalizability of the results. However, embedding the program in a theoretical framework and utilizing an evaluation model in the interpretation of the results may greatly reduce this limitation. As another limitation, however, the CIPP model is more comprehensive compared to other evaluation models, but it greatly emphasizes the process instead of focusing on the results. On the other hand, this characteristic helps policymakers of faculty development programs to systematically review all phases of these programs from various aspects (31). Also, this evaluation model should be planned for every educational program specifically due to the different and unique characteristics of each program, so the questionnaire designed and psychometrically analyzed in current research may need to be adjusted or modified for implementation in other settings.

Therefore, due to the constant challenge in medical universities regarding the insufficient participation and lack of interest of clinical faculty members in faculty development programs, we recommend considering the results of the present study to review and re-implement these programs.

Conclusion

Clinical faculty members are a most significant resource. Investing in their development is vital in improving capacities at all levels of the educational continuum. The Key features of effective faculty development for clinical faculty include evidence-informed educational design, relevant content to the participants' needs, longitudinal program design, multiple teaching methods such as flipped classrooms, incorporation of reflection, and group discussions.

Ethical considerations

This work was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education. Tehran. Iran. Grant No.4000568.

Conflict of Interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the faculty members who participated in this study for their support and involvement.

Received: 2022/05/1 | Accepted: 2022/09/12 | Published: 2022/09/16

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |